^m^mlmmmmmimms 9080 02618 2078 3 mWfWUWJUMWim

advertisement

MIT LIBRARIES

DUPL

3 9080 02618 2078

mWfWUWJUMWim

^m^mlmmmmmimms

LIBR^MES

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/bubblescapitalflOOcaba

DE^yVEY

HB31

.M415

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Bubbles and Capital Flow Volatility:

Causes and Risk Management

Ricardo

J.

Caballero

Arvind Krishnamurthy

Working Paper 05-20

August 25, 2005

RoomE52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

This

MA 02142

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Network Paper Collection at

Social Science Research

http://ssrn.com/abstract=803030

I

!

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHISIOLOGv

NOV

1

4 2005

LIBRARIES

I

Bubbles and Capital Flow

Volatility:

Causes and Risk Management

Ricardo

J.

Arvind Krishnamurthy*

Caballero

This version: August 25, 2005

Abstract

Emerging market economies are

estate

and other

fertile

ground

for the

development of

financial bubbles. Despite these economies' significant

potential, their corporate

and government

real

growth

sectors do not generate the financial

instruments to provide residents with adequate stores of value.

Capital of-

ten flows out of these economies seeking these stores of value in the developed

world. Bubbles are beneficial because they provide domestic stores of value and

thereby reduce capital outflows while increasing investment. But they come at

a cost, as they expose the country to bubble-crashes and capital flow reversals.

We

show that domestic

underdevelopment not only

financial

facilitates

the emergence of bubbles, but also leads agents to undervalue the aggregate

risk

embodied

in financial bubbles.

be welfare reducing.

We

alleviate the bubble-risk.

study a

We

In this context, even rational bubbles can

set of

show that

capital inflows and structural policies

"collateralized"

JEL Codes:

by future revenues,

aggregate risk management policies to

liquidity requirements, sterihzation of

aimed at developing public debt markets

all

have a high payoff in this environment.

E32, E44, F32, F34, F41,

GlO

Keyw^ords: Emerging markets, bubbles, excess

reversals, public debt market, financial

•Respectively:

MIT and NBER;

krishnamurthy@northwestern.edu. This

Conference Series on Public Policy.

Rigobon, and the referee

for their

underdevelopment, dynamic

Northwestern

is

We

volatility, crashes, capital flow

E-mails:

University.

paper has been prepared

are grateful to Douglas

for the

inefficiency.

caball@mit.edu,

a-

2005 Carnegie- Rochester

Diamond, David Lucca, Roberto

comments. Caballero thanks the

NSF

for financial support.

Introduction

1

Emerging market economies (EM's) are plagued by episodes

These episodes begin with a "bubble" phase where

and capital

Examples

mid

inflows, all grow,

economies

credit, investment, asset prices,

and end with a bust phase when these variables

of these episodes include Argentina in the 1990's,

Mexico

1990's,

of bubble-like dynamics.

in the early 1990's,

Chile,

collapse.

South East Asia

in the

Mexico and other Latin American

in the early 1980's.

Academic

theories of bubbles focus on two elements: the role of information in

coordinating agents' actions to grow and ultimately prick bubbles; and, the role of the

macroeconomic environment

in facilitating bubbles.

We

present a model that draws

on the second element.

We

first

element

namic

for

argue that an aggregate shortage of stores of value

bubble formation highlighted

inefficiency)

—

is

sector

stores of value to the economy.

government to

is

EM's

Fiscal

literature

(i.e.

dy-

Poor investor protection,

and sovereign-default concerns

issue reliable debt.

financial systems.

the key

is

unable to capitalize future earnings and provide

McKinnon

nancial repression" that, for example,

aspect of

macroeconomics

prevalent in emerging markets.

means that the corporate

ability of the

in the

— which

The

also

hmit the

These factors contribute to the

"fi-

(1973) has argued to be a prominent

limited investment outlets, such as poor bank-

ing systems and conglomerates with severe corporate governance problems, receive

investment flows despite their deficiencies. Real estate investment, which

is

one of

the best protected investment vehicles in EM's, serves as prominent store of value as

well. Finally,

where possible, agents actively seek high quality stores of value abroad

by purchasing developed economies' safe

In this context,

EM's

assets.^

present a fertile macroeconomic environment for the emer-

gence of bubbles. Starting from this premise, we develop a simple overlapping generations

(OLG) model

of stochastic bubbles. In the model, the absence of an adequate

quantity of high-quality domestic financial instruments to store value induces domestic

agents to seek this financial service abroad through systematic capital outflows.

These outflows are costly

for

EM's because they

divert resources that

may

otherwise

be spent growing the domestic economy; foreign interest rates are low relative to

'In this light, the surge in

demand

for U.S. assets since the late 1990s, is

shortage of high-quaUty stores of value in

period.

EM's

a symptom of the

following the crash in local bubbles during that

these economies' growth potential and marginal product of capital. For reasons akin

economy

to those found in the closed

on dynamic

literature

inefficiency, the

tween low external returns and high domestic growth rates creates a space

bubbles on unproductive local assets to

gap be-

for rational

For concreteness, we refer to these as

arise.

Real Estate Bubbles. They are a response to agents'

demand

for

more

profitable store

of value instruments.

In the classical

OLG

is

unambigu-

(see,

Samuelson

model, the emergence of these rational bubbles

ously good as they complete a missing "intergenerational" market

1958 and Tirole 1985).

This

is

the case, at least in an ex-ante sense, even

if

these

bubbles can crash as in Blanchard and Watson (1982) and Weil (1987). In contrast,

in the

emerging markets setup we describe, the presence of

fragility in

bubbles can

render them socially undesirable, despite their service as a store of value.

We

OLG

modify the standard

issues that

we

are interested

in,

model

and

in

two ways to address the emerging markets

to arrive at our results.

investment, rather than consumption, related

demand

for

First,

a store of value. Each gen-

eration of agents has an entrepreneurial and a banking sector.

when agents

arise in the entrepreneurial sector,

are old.

Investment projects

Young agents demand some

liquidity in order to fund these future investment projects. Second,

tantly,

we

follow Caballero

need to import international goods

market

is

To

in order to

undertake investment projects. How-

segmented from the international capital market,

for

endowment

amount

places a ceiling on

We

investment projects.

their investment

with international investors, we endow each generation

facilitate trade

of domestic agents with a limited

ternational

in the

At the margin, domestic entrepreneurs

and international investors do not lend to domestic agents against

projects.

and more impor-

and Krishnamurthy (2001) by modelling constraints

domestic and international capital market.

ever, the domestic capital

we introduce an

of international goods/collateral.

how many goods

The

in-

the country can import

assume that only the domestic banking sector has the

capability to lend to the entrepreneurial sector.

The

international goods

turing the idea that an

future.

ment

The high growth

of a bubble.

the old

EM

sell

endowment

As

endowment

grows

fast

rate of this

in the

of the generations grows at a high rate, cap-

and

will

be able to import more goods in the

endowment

standard analysis of

creates

OLG

some space

for the develop-

models, welfare

may improve

if

a bubble asset to the next generation, collecting their international goods

in

exchange, and so on.

We

study an economy with a stochastic bubble

that provides the required liquidity to young agents, but

may

burst at am- date.

Our main

result can be understood

by considering the liquidity demand

These agents purchase a portfolio

bankers.

liquidity

foreign

(i.e.

bank account)

when

trepreneurial sector,

to repay all loans, in general the

if

bubble asset and international

be

in a position to lend to the en-

the entrepreneurial sector cannot

banker receives a return that

marginal product of entrepreneurial investment. In particular,

both bankers and entrepreneurs are unable to

international

endowment

entrepreneurial sector

liquidity chosen

is

young

of the

in order to

However,

old.

of

sell their real

if

commit

lower than the

is

the bubble crashes

estate holdings for the

of the next generation. In this event, the investment in the

constrained by the ex-ante portfolio share of international

by bankers and entrepreneurs. However, since the banker does not

share fully in the return of entrepreneurial investment, the banker has a lower incentive to store the international

goods that are required, at the margin, to finance

entrepreneurial investment projects in the crash, and

We

more

of

all

an incentive to chase

show that welfare

is

often improved

During the growth phase of the bubble, the economy sustains high

levels of invest-

the higher return promised by the bubble.

by reducing investment

in the bubble.

ment. Entrepreneurs and bankers are able to

liquidity with

sell their

which they finance investment projects.

bubble asset

for international

Capital inflows during this

period are high as agents are actively borrowing against the international collateral

of the country.

Domestic credit grows as bankers are flush with resources to lend

to the entrepreneurial sector.

When

the bubble crashes, entrepreneurs and bankers

are unable to trade for the international liquidity of other agents.

domestic credit and investment

verse,

bubble dynamics

An

cerns

in

falls. ^

Capital flows re-

Thus, our model successfully reproduces

emerging economies.

important policy discussion in emerging markets (and developed ones) con-

managing the

risks created

by a bubble. In our model, rational bubbles

arise

endogenously as a result of the economy's dynamic inefficiency but can be welfare

reducing, because the private sector underestimates the costs of fragility.

There are two types of

policies that

can improve upon this outcome. The

first

are

short-term risk-management policies that aim at discouraging excessive reallocation

of liquidity

^This

is

and savings toward

local real estate.

in stark contrast witli the canonical

OLG

Banking regulations such as

model, in which bubbles crowd out private

investment, so that the bubble and private investment are negatively correlated.

Farhi and

Hammour

inter-

See Caballero,

(2004) and Ventura (2004) for models that also exhibit positively correlated

bubbles and investment.

These

national liquidity requirements reduce bubbles.

policies are similar to those

discussed in Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2004) in the context of overborrowing and

the dollarization of habilities problems.

sterilization of capital flows.

A

more novel

We show that

if

model

liquidity policy in our

is

the government has sufficient capacity to

tax current endowments, then by issuing one-period government debt and using the

proceeds to directly invest in international liquidity, the government can insure the

private sector against the fragility of the bubble. In the crash, the government injects

its

international liquidity to offset the insufficient liquidity of the private sector.

The second type

these economies.

of policies are

They

more

directly linked to the source of bubbles in

are aimed at improving the supply of domestic financial assets

whose prices are not governed by bubble dynamics.

has sufficient credibility and

enough public debt

commitment

We

show that

a government

if

to securitize future taxes, then

(a sort of collateralized

Diamond, 1965, debt)

to

it

can issue

crowd out the

bubble while solving the dynamic inefficiency problem.''

The paper

is

related to several strands of literature.

rational bubbles in general equilibrium,

and

builds on the

It

work on

on Tirole (1985) and on

in particular

the segmented markets version in Ventura (2004). However, unlike the conclusion of

these papers and that of

much

of the literature, bubbles

may

be socially

inefficient in

our model. This insight informs most of our discussion.

Saint-Paul (1992) also develops a model where rational bubbles

inefficient.

However

his context is entirely different

More

capital spillovers.

focus on fragility,

that of Caballero, Farhi and

is

socially

from ours, as in his case the

inefficiency arises from bubbles crowding out physical capital in an

model with positive

may be

endogenous gi-owth

closely related to our paper in

Hammour

terms of the

(2004) where bubbles

may

increase the chance of a crash in a multiple equilibria economy. In their context too,

the reason

why

Instead, in our

itself

this

is

potentially inefficient

is

an externality

in capital

model the welfare implications stem from the

and from the private

accumulation.

riskiness of the

bubble

sector's distorted perception of the aggregate risk of their

choices.

In the literature on liquidity provision,

Holmstrom and

Tirole (1998) note that

financial constraints lead to too little stores of value. In this context, they

government debt can improve on the allocation

^Of

course, this solution

pledge future taxes

itself

may be

may be

of the private sector.

fragile in itself, as expectations over the

variable.

But

show that

Hellwig and

government's ability to

this is uncertainty of a very different nature, unless

it

can feedback into the governments ability or commitment to deliver on each of these fronts.

in

Lorenzoni (2004) study an economy where agents have limited commitment in repaying debt contracts.

They show

that in economies which are dynamically inefficient,

long term debt can be sustained even under this hmited

commitment

constraint.

In terms of the source of the pecuniary externality and private undervaluation of

international liquidity, the

murthy

mechanism

is

similar to that in Caballero

However, the focus on these papers

(2001, 2003).

is

and Krishna-

on the externality and

not on the possibility of bubbles, their efficiency properties, and solutions to manage

bubbles. Moreover, in the current paper the main problem

not one of insufficient

is

country-wide international liquidity during crises but one of significant capital outflows due to a coordination failure.

emphasis on preventive policies to manage bubble-risk rather than ex-

Finally, our

post interventions contrasts with the views expressed by,

Bernanke (2002)

for

Dornbusch (1999) and

developed economies, where ex-ante and ex-post interventions

take a more balanced role.

that while developed

e.g.,

The main reason

for

our emphasis on ex-ante policies

economy policymakers can count on

is

access to resources during

a bubble-crash, EM's governments and central banks often find themselves entangled

in the crisis itself.

The paper

is

organized as follows. Section 2 describes the structure of the economy,

while Section 3 introduces bubbles. Section 4 establishes the excessive volatihty of the

market outcome with bubbles. Section 5 and 6 discuss aggregate

and

financial

A

2

market development

risk

management

policies, respectively. Section 7 concludes.

Productive Dynamically Inefficient Emerging

Economy

The emerging economy

is

OLG

populated by an

produce and consume only when

old.

of risk-neutral

There are two types

domestic agents that

of goods, international

and

domestic goods. The domestic goods are perishable, but the international goods can

be saved abroad

at the world interest rate of r*.

Domestic goods and international

goods are perfect substitutes in the domestic consumers' preferences. While

for inter-

national investors, only the international goods are tradeable and offer consumption

value.

These assumptions

effectively limit foreign investors' participation in

domestic

markets.

Each agent

is

endowed with some date

t

goods and some date

t

+l

goods. Agents

are born at date

receive an

t

with an endowment of Wt international goods.

endowment

of

RKt

endowment

as the returns

with. Thus,

endowments

At date

i

+

from a domestic plant of

at

(i, i

+

1) for

produces RIt+i units of domestic goods

an agent born at time

for

t

born

is

are {Wt, RKi).

become entrepreneurs, and

i

an investment of

direct investment opportunities, but

entrepreneurs (see below).

We

may

/(+i units of international

The bankers do not

This production occurs instantaneously.

goods.

receive

any

be in a position to lend to the investing

note that agents are ex-ante identical, while ex-post

heterogeneity.

is

We

can think of the latter

Ki that the agent

size

one-half of the agents of generation

1,

We

1).

old, agents

become bankers. The entrepreneurs receive an investment opportunity, which

one-half

there

>

domestic goods [R

When

are centrally interested in

how

the young agent saves his international goods

to finance investment (directly or indirectly)

that the young agent saves

rate of r*

.

generation

Let

i,

W^

all

when

old.

For this section, we assume

of his international goods abroad at the world interest

denote the international goods available at

i -t-

1

to a

member

of

so that:

Wl={l + r')\\\.

At each date there

is

a domestic financial market, where entrepreneurs with

vestment opportunities borrow from bankers. The financial market

in the

same sense

as production

is

instantaneous.

At date

i

+

1,

is

in-

instantaneous

an entrepreneur with

an investment opportunity borrows U+i international goods from a banker, offering to

repay pt+i/j+i domestic goods when production

is

complete.

We

impose a

collateral

constraint on this loan;

Vt+ih+i

where

ip

^The

parameterizes the tightness of the collateral constraint.''

collateral constraint

we have imposed

output from the new investment of /j+i

different

< ipRKt

is

requires that loans be collateralized

not considered collateral.

by xpRKi

.

Any

This latter assumption

is

than the standard credit constraints model, which would require that

Pt+ih+i < i'RiKt

where again

tp

<

1

+

It

+ i)

parameterizes the tightness of the collateral constraint.

borrower saturates this collateral constraint,

Assuming that the

yields:

pt+i

where the

first

term

is

the familiar "equity" multiplier that arises in models of credit-constraints.

Our model assumes

eign investors nor the

that the domestic capital market

young

of generation

t

+l

is

segmented. Neither

for-

participate in the loan market. Within

the logic of the model, this occurs because loans are repaid in perishable domestic

goods, which have no consumption value to either generation

vestors.

More

we

generally,

i

+

or foreign in-

1

think that foreign investors have limited participation in

debt markets because of lack of local knowledge, and fear of sovereign expro-

local

The

priation/selective default.

debt literature

(e.g.

Likewise,

limit.

latter concern

Bulow and

we think

is

studied extensively in the sovereign

Rogoff, 1989) which motivates a country-level debt

of the bankers of generation

dealing with the entrepreneurs of generation

/

as having

more experience

t.

Equilibrium in the loan market requires that,

1

<

Pt+i

<

R,

since at a price below one, lenders will not lend,

will

and

at a price above

R

borrowers

not borrow.

The supply

of loans

WI/2 and

is

assume throughout that

tJjR

Utilizing these conditions,

we

<

I

the constrained

demand

for loans is

and we normalize quantities and

set

^^^'

We

= Wf

.

Kt

find that in equilibrium:

Vi+\

=

1,

so that bankers, in equilibrium, have international goods that are not lent to the

entrepreneurs.

On

average, emerging market economies grow

assuming that the endowments (Wi, R^i) grows

g>r*

fast.

We

capture this feature by

at a rate g such that:

.

Substituting this expression and solving for the amount borrowed, yields:

As the domestic

capital

market

is

segmented, the aggregate supply of loans comes from the resources

of bankers. In total, the loan supply

is

W('/2 and the aggregate

demand

for loans

is

li^\j2. Thus,

pt+i =max[l,i^'/?(2-l- A'(/VK/)] =max[l,3i/>/?]

which

some

is

very similar to the expression we derive under our assumption. Our assumption simplifies

of the algebra later in the paper without distracting from the substance of the results.

.

Thus, our basic economy behaves as a dynamically inefficient economy, in the sense

that store of value (rather than the marginal product of capital) has a lower return

than the rate of growth of the endowment.

In this context,

many

dynamic

means that the country

is

At each time

a capital outflow of Wt and an inflow of

there

f

the net outflow

is

lending (or leaving) too

positive outflow

omy.^

is

of value instrument

(1

+

>

0.

r*)Wt-i, thus

Wt -

+

(1

r*)Wt-i

=

-

[g

r*)Wt-i

highly inefficient for a resource-scarce emerging market econ-

among domestic

demand

for a higher return store

agents.

Real Estate Bubbles

3

Young agents need a

store of value to finance investment opportunities

In the basic structure

arise.

is

=

also hints at the presence of a large latent

It

international goods abroad.^

is:

NetOutfloiUt

The

inefficiency

dynamically

inefficient

we have

outlined, the (saving side of the)

and the only store

of value

abroad at the safe but low world interest rate of

The

familiar

Wt endowment

their

there

>

r*

on

inefficiency

no mechanism

is

is

for all

genera-

Rather than lending Wt abroad, the young transfer

of international goods to the old,

its

economy

r*

and when

Wt+i endowment of the new young, and so on. Each generation,

a return g

these

lending international goods

is

Samuelson (1958) solution to dynamic

tions to enter a social contract:

when

old, receive the

effectively, receives

OLG

model

and young to write such contracts. Thus,

in the

international goods endowment.^ However, in an

for the old

context of emerging markets that concerns us here, the

OLG

assumption captures the

dimension of financial underdevelopment that limits contracts beyond a small groups

of

contemporaneous market participants.

We

suppose that in this context an unproductive and irreproducible asset

estate," for short)

price

A

only

traded domestically. Since the asset

must be a pure bubble.

We

if

unproductive, any positive

is

necessarily fragile, as the asset retains value

current generations expect that future generations will

^This

is

is

is

"real

denote this price by Bt.

positive price on the bubble asset

by Abel

®It

is

(

demand

the asset.

We

the analog to the corporate-cash-flow empirical concept of dynamic inefficiency proposed

et al (1989) for the context of closed economies.

only matter of relabeling to translate these excessive outflows into depressed inflows.

^And the

first

generation receives an additional return.

capture this fragility by assuming that as of time

across generation ends,

and the young of i +

abroad instead of purchasing the bubble

1

t,

with probabihty A the coordination

choose to save their international goods

asset. In this case, the

bubble crashes to a

value of zero.

If

the bubble does not crash,

the interest rate

(this is

is

grows at the rate

it

t^.

We

at the highest possible level consistent

focus on the case where

with rational expectations

the only case where the bubble does not vanish asymptotically in the absence

of a crash), so that:

r^

Thus the expected return from investing

?>

=

g.

in the

bubble

is

= g-\{l+g)

and

B.t+\

^l +

r^

= {l-\){l+g)<l+g.

B,

If

invest

A

is

not too high and the spread

some

A

.b

—

r*)

is

sufficiently large, agents

of their international goods in the bubble. This will hold true as long as:

rb-r* = {l-\)/\? -\{l +

Recall that the young at date

t

are

endowed with

!•*)>{}.

(VFj,

RKi). They divide

holdings of the bubble asset and saving in the international market.

share of bubble assets in the portfolio by aj, and

held by generation-i at date

i

+

f is either g (no crash) or

At date

i

transactions.

return f

.

+

1,

We

W't into

denote the

write the international goods

1 as:

W[ = Wt{l +

where

now

(1)

—1

r*

+at{f-r*))

(crash).

an entrepreneur with an investment opportunity enters into two

First,

he

sells his

bubble asset to the next generation to receive the

Next, he borrows U+i at price pt+\ from the bankers, to yield total output

of,

•

RKi + RW[ + {R -

Pt+i)lt+i,

where

^(+1

< -.*^K..

Pt + l

10

.

As long

Assuming

output

as pt+i

<

R,

it

much

pays for the entrepreneur to borrow as

now and

this case for

,

maximum

substituting in the

as possible.

loan size gives total

of,

RKt + RW; + {R- p,+,)^Kt.

Pt+i

A

banker at date

t

+

to the next generation

1

goods by selling his real estate assets

collects international

and then lends these goods, along with any savings from date

As a

international lending, to the investing entrepreneurs.

total

goods

bankers receive

of,

RKt +

Rolling back to date

or bankers at date

bubble asset to

t

+

t

1.

W'iPt+i.

agents are equally likely to find themselves as entrepreneurs

Thus the

decision problem

is

to choose a portfolio of the

solve:

+

DL-max X?

W,

+ W'^+P'

Ei<f Rht

'2

,

0<at<l

At an

result, the

t

interior solution

order condition

{

^ - Pt+1

I

,

-{

2

— ht>.

i^R

/„s

\

,.

pt + i

(2)

J

(we make parameter assumptions so this

is

the case), the

first

is:

(1

-

^)l^(^ + pf+i)

MR + p?+i)

-

=

(3)

where pf^^ and p^j represent the equilibrium price of loans when the bubble survives

and crashes,

respectively.

In words, the young agent gets an excess return of

crash,

if

which happens with probabihty

the bubble does crash.

When

1

—

A.

He

Ar^

the bubble does not

trades this off against the loss

old, the agent is either

an entrepreneur,

the returns from the bubble funds investment that yields R;

in

if

or,

in

the agent

(

— 1)

which case

is

a banker,

which case the returns from the bubble are used to lend to the entrepreneur at the

price pt+i

Thus returns on

The supply

entrepreneurs

of funds

is

at

R + pt+i

the bubble are valued by the agent aX

from bankers

is

at

most

VV^

,

while the

most S^Kt- Thus, market clearing

demand

in the loan

for

.

funds from

market yields

for

the no-crash state,

pf,

Note

1

= max

—

< 1

that, as in the previous section,

when

tl)R

<

1

we

find

p^

=

1.

For the crash state, market clearing yields:

pf

= max

mm —

.

1

.

,

<

jjR

rj-

,

l+r*){l-at)'

11

H„

(4)

We now

script

consider the equilibrium determination of pf and

p stands

problems are the same

First note that agents' decision

for private).

(where the super-

a'l

across each period that the bubble does not crash. Thus, without loss of generality,

we drop time

Denote

subscripts.

a^{p'^) as the solution to the agents decision problem, (2), given

note p'^(a) as the solution to the market clearing condition,

We

(4),

p'-'

.

De-

given choices of a.

are looking for a fixed point {a^,p'-^) that solve both (2) and (4).

We

begin the characterization by considering

program, the solution

is

a step function. Note that

the objective with respect to

a

Given the linearity of the

a''{p'-'').

=

if p*"

then the derivative of

1,

is:

il-X)-^^{R + l)-X{R + l)>0

+

1

where the

asset

last inequality follows

dominates saving

r*

by condition

(1).

In words,

bank account,

in the international

an adjoining assumption by considering the case where

possible).

At

this price, the derivative of the objective

= R

(the highest value

is:

assume that

(l-A)Ar^-A(l +

which can hold along with condition

Ari'+'i+r*

-

Under condition

dominates saving

Conditions

is

so that

p'-^

= 1, the bubble

a = 1. We make

+ r*

1

We

if p'-'

(1)

in the

and

illustrated in Figure

(1) as

=

(5), if p*"

9/?

r*)^^<0

long as

/?

>

1

(5)

and

^^t^_L^n|^r)_(_^^6)

< A <

saving in the international bank account

/?,

bubble asset.

(5)

guarantee an interior solution to our problem. The solution

1.

The

solid line depicts a^[p'^), the step function solution

to the agents decision problem. Note that under conditions (1) and (5) there exists

a unique value of

condition

is

p*^

that

satisfied

lies strictly

between zero and one, whereby the

with equality. The s-shaped dashed curve in the figure

solution to the market clearing condition,

In

first

summary, under

agents hold a fraction

(1)

<

and

qP

<

(5), in

1

p'~'{n).

The unique equilibrium

its

return

is

the

at point

each period that the bubble does not crash,

of their portfolio in the bubble asset. If the bubble

crashes, the banker's (gross) return in the loans market

bubble does not crash,

is

order

is

ingredient in the welfare statements

p^

=

1.

we make

12

is

1

<

p"^

The banker's return

next.

<

of

/?,

p

is

while

if

the

the central

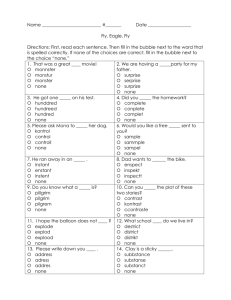

Figure

1:

Equilibrium determination of a^ and

P^

Solution to

Decision Problem

ap

a

Notes:

The

figure illustrates the equilibrium determination in the crash state.

the decision problem for agents traces out the solid-tine step function.

If

The

solution to

agents expect higher

returns on lending international liquidity in the crash-state, they cutback on purchase of bubbles,

and increase

their holdings of international liquidity.

market clearing condition as a result of these choices.

then

in

higher,

less

If all

international liquidity

traces out the

agents hold more of the bubble asset,

if

the bubble crashes and

P

will

be

a^ denotes the equilibrium.

Excess Volatility

4

If

equilibrium there will be

The s-shaped dashed curve

A

=

0,

and the bubble

is

not

fragile,

then

its

existence

is

unambiguously beneficial

(Samuelson 1958).

4.1

Crash and Credit Crunch

However,

ment

will

it

seems extreme to assume that a coordination-dependent financial instru-

always be stable.

When

A

>

0,

the

economy trades higher

(or lower net outflows)

while the bubble

reversal in capital flows

and the consequent crash

is in

13

capital inflows

place, for the possibility of a

in the

sudden

domestic real estate market.

.

Consider the expression

for total

output at date

^

If

there

is

no crash, then W^

is

high and

^^W,

(1

+

f/B

=

Starting from this level,

are

two

if

r*

+

t:

2

75(+i

a,Ar'')

we consider the

=

+

pt+i

=

p^

!(/?

Output

1.

-

\)i>RK^

date

effect at

i

+1

in this case

+

is,

RK,.

of a

fall in

W[, there

falls,

curtailing

effects that arise.

First, the direct effect

his date

is

that the investing entrepreneur's wealth

investment and reducing output. In the case of the crash, wealth

i

falls to

(l-Q,)M';(l+r*).

Second, the banker has

i

+

1.

As

less

funds to lend to the investing entrepreneur at date

real estate falls in value,

banks are unable to

collect as

much

goods from the next generation, and so they cut back on loan supply.

the supply of funds

is

sufficiently large, the result

interest rates rise causing investment

is

and output

which entrepreneurial investment

at the point at

international

If

the

fall in

a domestic "credit-crunch''

loan

:

This credit crunch occurs

to

fall.

is

constrained by the quantity of

international goods of the current generation of bankers

point, since the supply of loanable international goods

is

and entrepreneurs. At

this

limited, banks' loan interest

rates rise above one.

At date

agents choose at and this leads to variation in \\\. 'We define a "small

i,

crash" as a circumstance where at

enough

fall in

W^ that only the

f^cs

However,

in pt+i

if

at

is

"large crash."

sufficiently large

crash case

is

From Figure

where at

in the

1,

small, so that the bubble crash leads to a small

first effect arises.

^ ^-LlwtiX -

above one, resulting

is

we

at)[\

+

r')

In this case,

+ h^R - \)^RKt + RKf

then the contraction

in loan

supply leads to a

domestic credit crunch. 'We refer to this event as a

see that the threshold between the small and large

= a^

In the large crash, p^^^ rises above one to

q i^.tH^ y

We

can substitute and find

that,*^

The complete

U = R mm

expression for the output in the case of both large and small crash

<

(1

—

rise

Q( ) Pv J

,

>

14

+ max

<

,

is:

>

+ Rh

t

This

expression

last

intuitive. In the large crash, all of the international

is

the bankers and entrepreneurs are being invested at date

goods produces a gross return of R, which

t

+ 1.

Each

in addition to the

goods of

of these invested

endowment

RKt,

of

yields the expression for U^'^.

Finally, the crash in the

The next

of value.

bubble asset leads to a permanent

generations invest

all

of their

domestic stores

loss of

endowment abroad causing

capital

outflows.^

Overexposure to Large Crashes

4.2

Although bubbles lead to the

possibility of crashes, they

increasing growth while they last.

the

economy make

We

show that the private

do provide the benefit of

The next question we address

this risk/return trade-off optimally

is

whether agents

from society's point

of view.

sector's choices lead to overexposure to large crashes.

Consider the choice of at that maximizes expected aggregate output (which

equal to the generation

in

i's

welfare),

when

at

is

such that the economy generates a

is

large crash:

max

XU^'^

+

- X)U^

(1

(6)

a'^<a(<i

The

derivative of this function with respect to at

(l-A)(/?

+

Ar*

l)

at the

optimum

case from (3)

r*

for private agents, the first order condition for the large crash

is:

{I

When p^i =

2XR.

+

I

But

is:

/? it is

- X){R +

= X{R + pf^,).

1)^^

evident that these two

first

order conditions coincide, and the

However,

if

p^i < R, then the

planner's solution to the program in (6) yields an Qj that

is

strictly smaller

private sector's choice

The

is

constrained

distortion in the agents' decision can be

the banker's portfolio decision.

^

efficient.

An example

of this

phenomena

At date

in practice

+

t

may

most

I,

easily understood

social

than qP.^°

by considering

the value of international goods in

be the behavior of EM's following the

EM

crises

of the late 1990s. These economies turned aroimd from being significant net borrowers before the

crises, to

become

substantial net lenders to the developed world, and the

^"It is clear that

p^i <

that qP

Ris

We

the

first

US

in particular.

order conditions differ between the private and planner programs

can assert that Q(

is

strictly smaller

than a^ because conditions

at an interior, so that at least one of the first order conditions

•

15

is

(1)

valid.

and

(5)

when

guarantee

.

the crash-state to the banker

.

proportional to pf+i-

is

international goods in the crash-state

However, the social value of

proportional to R, since these goods are

is

always used by entrepreneurs to undertake investment projects."

that

p^i < R, the banker has

less of

To the extent

an incentive to ensure that he has sufficient

international goods to lend to entrepreneurs in the crash-state. Moreover, recall that

r

p,,

,

=

mm

^^

—

r

<

-,

R

so that less domestic financial development, captured by smaller values of

p^j and increases

lowers

ip,

this distortion.

Ex-ante, the low return on lending to entrepreneurs translates into a lack of pru-

dence in the date

/.

Bankers chase higher returns by investing

portfolio decisions.

excessively in the risky real estate bubble, rather than retaining

some international

liquidity to be in a position to lend to the entrepreneurial sector.

Lack

of financial

development, in the dimension of tighter domestic collateral constraints, overexpose

economy

the

Welfare Maximizing Choice

4.3

We

to the risky bubble.

conclude this section by deriving the welfare maximizing portfolio share.

For each generation that the bubble does not crash, the planner chooses a to solve:

max XU^ + (1-X)U^.

(7)

0<a<l

There are two cases to consider

note that

Ua >

a^

p'-^

p'-'

,

W^ =

Thus,

We

=

1

>

in deriving the solution. If

a <

and the economy avoids the credit crunch. In

I

and the economy enters the credit crunch

a'^,

from Figure

this case, t/^

if

=

we

if^-^

the bubble crashes.

U^'^.

note that under

(5),

the

first

order condition that maximizes (7)

f/*^'-^,

indicates choosing the lov/est possible value of a.

from

(1)

that in the range where

U'-^

=

t/"^"^,

the

On

first

when

the other hand,

it

the boundary where

a

is

the credit crunch situation.

1,

some

—

order condition indicates

lie

at

equal to a^

In v/ords, a social planner chooses an

=

U'-'

follows

choosing the highest possible value of a. Thus, the welfare maximizing a must

'^When pf^i

1

a that

is

as large as possible so as to avoid

This choice maximizes the intergenerational transfers

international goods stored by the bankers/entrepreneurs go unused by the

entrepreneur. For this reason, the undervaluation argument only applies in the case of large crashes.

16

afforded by the bubble, while avoiding the credit crunch where international goods

are scarce.

due

is

We

also note that the stark result of avoiding the credit

to the linearity of our model,

and conditions

(1)

and

(5).^^

crunch completely

On

the other hand,

the model does highlight the novel aspect of our welfare analysis of bubbles.

Aggregate Risk Management Policies

5

We now

focus on the case where the rational real estate bubbles are welfare reducing

and consider a

variety of corrective

government

policies that

implement qP

=

a^.

In practice, a bubble crash in a developed economy leads the central bank to inject

liquidity into the banking sector to offset the credit crunch.

may

be helpful in our model, in practice

governments

bank are

banking

in EM's.^'^ In a

likely to

us unlikely to be readily available to

bubble crash, the credibility and Hquidity of the central

be low, so that the central bank

sector. Thus,

we

the exposure to bubble

is

in the

same

position as the

aim

focus in this section on ex-ante policies that

to reduce

risk.

Liquidity Requirement

5.1

One

it

While such a pohcy

solution to the risk problem

we have

raised

is

agents of generation

for all

enter into a contract requiring that each agent hold a fraction

(1 — a^)

t

to

of their wealth

in foreign reserves.

The most

natural interpretation of such a social contract

requirements on the banking system. Such requirements are

ing markets.

is

in

terms of liquidity

common

in

many emerg-

For example, during the period of Argentina's currency board banks

were required to hold significant dollar-reserves.

But such a

solution requires

some

policing

tive for one agent to deviate from holding 1

I

— a^

.

From Figure

1,

bursts, the credit crunch

we

is

agent's decision problem at

'^For example,

(5)

is

see that

p'-^

=

and enforcement. Consider the incen-

— a^ when

1 at q'^

avoided). But, from the

p*^

when A goes toward

=

1 is

a =

1.

An

all

(i.e.

same

other agents are holding

at q'^, even

if

the bubble

figure, the solution to the

agent will prefer to invest only in

zero, intuition suggests that the

optimal q will

rise.

However,

violated in this case.

'^See Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2005) for a model of (ex-post) extreme events interventions

in

economies with developed (complete) financial markets.

17

the bubble asset.

We

^'^

can also see

agent to choose

where the

this

a =

1

by considering the program in

versus

a

=

if all

,

from

last inequality follows

Intuitively,

a^ when p^

=

(2).

The

utility gain for

an

1 is,

(1).

agents are holding sufficient international liquidity, a crash avoids

the credit crunch. Thus, a deviating agent values the bubble asset purely for the ex-

pected return

it

offers

and does not assign any additional cost to the bubble crashing.

This leads the agent to invest

If

portfolio decisions are costly to observe, a liquidity requirement will be costly

to impose.

the costs are high enough, the

If

we have described

5.2

An

of his wealth in the bubble asset.

all

earlier

=

where a

economy

will revert to the equilibrium

a''.

Capital Inflow Sterilization

alternative policy to implement the optimal investment in the bubble

inflow sterilization.

As we show

is

capital

next, this sort of policy avoids the policing issues of

the liquidity requirement, but instead recjuires that the government having credible

powers of taxation.

Central banks often respond to capital inflows by sterilizing. They

debt proportionate to the quantity of the capital inflow. The practice

sell

is

government

conventionally

seen as an attempt to reduce the monetary expansion created by the capital inflow, but

note that, as

If

we show

the sterilization

bubble assets,

it

is

next,

large

it

has power even in the abscence of a monetary friction.

enough to provide the private sector with alternative non-

has the potential of reducing investment in real estate bubbles.

Government debt crowds out the bubble,

Suppose that the government

t

at interest rate rp. In addition,

goods endowment of generation

raising interest rates in the process.

issues one-period debt with face value of Gt at date

raises taxes at the rate of Tj

it

t.

The revenue from the debt

invested at the international interest rate of

^*Jacklin (1987)

He argues

makes a

r*.

is

and the tax are

sale

Finally, the debt

related point in the context of the

that the Diamond-Dybvig bank

on the international

is

Diamond and Dybvig

not coaHtion incentive-compatible

side-trades.

18

repaid at date

if

(1983) model.

agents can

make

—

i

+

1,

so that the government balances

+

rsWt

its

budget:

G

Y^)^^ + ^')-Gt=Q-

(8)

Agents purchase act of these bonds with their international endowment ("a capital inflow") at interest rate

W[ =

where

f

is

rf Then, the wealth equation

.

M/, (1

+

either g (no crash) or

r*

—1

+ acAr? -

decision problem for an agent

max

Et

0<QG,,+a,<l

We

<

at{f

-

generation

t

becomes,

r*))

(crash), and,

Wt = Wt{l The

+

r*)

for

is

T,).

now:

'2

RKt + W^

[

Kt

^:

1

2

pt+i

note that government bonds provide the same stable cash-flows as investing

the international

endowment abroad. Thus,

as long as acj,

+

ott

<

1,

government

bonds and international liquidity are perfect substitutes and rp must be equal to

r*.

From

the government's budget constraint, in this case

government debt are accommodated by a reduction

the private sector, and the sterilization has no

For the sterilization to have any

efl:ect, it

Tg

=

0.

Any

sales of

in the international liquidity of

eflPect.

must be

sufficiently large.

Again denoting

by qP the portfolio share that the private sector's optimally chooses to invest in the

bubble, the sterilization has any effect only

Gt>G: =

if,

{l-a^)Wt{l +

r').

Let us consider such "large" sterilizations. For these cases, the private sector reduces

its

international liquidity holdings to zero and only holds government debt and the

bubble

asset:

W;^Wt{l+rf + ai{f-rf).)

The

private agents'

(1

-

first

X){g

- rf){R + pf^,) -

At the welfare majcimizing

solving for rp,

order condition, at an interior solution for

solution

A(/?

+ pf+J(l +

we know that p^

we obtain

19

=

rf )

jf

=

=

1.

Qj, is

now:

0.

Rewriting, and

the government sells debt that raises (1

If

—

a''^)Wt resources at date

i,

agents

purchase both this debt as well as the welfare-maximizing amount of the bubble

any investment

asset. Since

government debt reduces investment

in the

asset one-for-one, the interest rate on the debt has to rise to

f'',

in the

bubble

the expected return

on the bubble.

However,

in

implementing the optimal portfolio share, the government has to

taxes. Using the government's budget constraint, (8),

some

=

r,

(1

-a^^

1

A

+

we can

raise

solve to find that,

r*

higher return on the bubble or a lower international interest rate, raise the required

taxes.

The need

government

to collect taxes to support the sterilization raises a concern.

is

limited in

its ability

sterilizations (or sterilizes with

of the public).

to raise taxes, then

it

bonds that have a low

But, small sterilizations have no

If

the

can only implement small

effective return, in the eyes

effects.

Thus, effective sterilization

requires a government with sufficiently large tax powers.

.J

Public Debt Market Development

6

Sterilization has the potential to solve the inefficiency

stemming from

agent's under-

valuation of the systemic risk generated by bubbles. However, the optimal solution

is

not to eliminate bubbles altogether, but to reduce their amount to a^ in Figure

1.

The bubble

is

the endogenous market solution to the dynamic inefficiency created

by domestic financial underdevelopment. Sterilization, as we describe

instrument to reduce the

fragility created

by

this

market

stitute for the missing "intergenerational" contract.

both reduce

fragility

and

alleviate

dynamic

solution.

Can we

inefficiency?

We

find

it, is

It is

merely an

not a sub-

mechanisms that

turn to answering this

question next.

The reason our

is

sterilization policy does not solve the

that the interest rate spread of

tion.

Thus, on net, there

This

is

in

is

f'-'

—

r* is

dynamic

inefficiency

problem

financed with taxes on the same genera-

no intergenerational transfer associated with

sterilization.

sharp contrast to Diamond's (1965) perpetually rolled-over public debt,

which does represent a solution to the dynamic inefficiency problem. However, Dia-

mond's public debt

is

a bubble in itself and hence raises the

20

same

fragility

concerns

surrounding the real estate bubble.

If

the next generation does not roll-over the debt,

the bubble crashes.

We

next show that public debt that

supported by future rather than current

is

taxes achieves a compromise: Such debt implements intergenerational transfers (like

Diamond), as well

as reduces fragility risk (like our sterihzation policy).

We

pledging future taxes requires credibility and commitment.

Of

course,

thereby establish a

natural connection between a government's credibility and ability to raise taxes and

the extent to which the government can solve the economy's dynamic inefficiency

problems, while limiting the fragility costs of the bubble.

Suppose the tax base of the government

is t\'\'\.

However, because of credibility

concerns the market discounts the future tax revenues at the rate

(1

—

p) such that

the pledgeable tax revenues are:

(1

We

assume that

at

t

-

p)VVK,+,

the government issues the

these future (potential) taxes.

5

>

0.

maximum debt

With such a debt

can, collateralized

it

by

structure, a high p can be interpreted

as very short-term maturity structure of debt, while a low p corresponds to a long-

term maturity structure of debt. Let the value of the stock of outstanding government

debt be denoted by Dt. The value

=

^

Wt

satisfies,

(l-/^)(l

of

-^E.|±i|.

+n

1

[

Assume, momentarily, that the stock

of agents' store of value

+ ^)|r +

Wt+i

government debt, Dt,

demand, that agents use

is

is

constant.'^ Let

r^ denote

D/W

is

sufficient to satisfy all

this as the only saving instrument,

maximum

and that the government maintains the practice of issuing the

debt at each point in time. Then,

(9)

J

equal to one at

all

this equilibrium interest rate,

collateralized

dates and the interest rate

which from

(9) satisfies:

^^=T(l-p)(l + r^)-/,.

It is

apparent from this expression that

that p

is

^^D/W

small relative to

is

r,

if

the government has enough credibility so

then the dynamic inefficiency can be completely removed

always equal to one, while the tax base

between these statements because,

collateral for the debt.

If all

is

equal to tU',

.

There

is

in equilibrium, the taxes are not levied; the)'

of the taxes of

rWt were

would shrink toward zero over time.

21

no contradiction

simply sen'e as

levied, then ratio of debt to

endowments

as the

r^ that solves the above equation exceeds

efficient equilibrium, the

g.^^

To implement

this constrained

government issues enough public debt to bring r^ exactly

to g.

While the pledgability

of future taxes

needs to collect taxes to pay

new

with

debt.

That

not bubbly since

To

it is

is,

for this debt, as it

is

debt

is

by taxes.

fully collateralized

by

collateralized

T—

1

will

— p)tWt

(1

buy up

fully repaid.

2 also

is

Suppose

t.

to (1

— p)tWt

young agent

1,

T—

T >

L

the young agent

of generation T, the

bond

knows

will

be

the young at generation

1,

Since every bond in the stock of government

so on.

collateralized by a specific, dated, tax revenue, the

entire stock of

T—

at date

face value of this bond, since he

Anticipating this behavior by generation

buy the bond, and

bond matures

this

revenues. Then, at date

that regardless of the behavior of the

debt

fully finance the expiring

see the role of collateralization, consider one of the bonds in the stock of

of generation

T—

can

the collateralized debt behaves as Diamond's debt, but

outstanding government debt at time

and

the government actually never

critical,

is

argument applies to the

government debt.

The same argument does

not apply to Diamond's debt solution, or the real estate

T—

bubble. In these cases, the young of generation

they believe that the young of generation

coordination dependent asset

T

1

buys the bubble only because

do likewise.

will

Of

course, such a

is fragile.

Collateralized public debt also dominates the real estate bubble as a savings vehicle

since:

r^ -

The

f*

=

-

r^

+

5

A(l

-f

collateralized debt eliminates the bubble,

Note that

then even an infinitesimal tax base

more

> r^ -

and

is

p

>

0.

its fragility.

where the government

in the limit case

public debt.^' In the

5)

is

fully credible, so that

enough to implement the

realistic case of a

first

=

0,

best with stable

government with limited

government may be unable to generate enough

p

credibility, the

reliable store of value instruments to

^^For smaller values of r relative to p for which the government cannot issue debt such that

D/W

if

ecjuals one, there

is still

parameters allow for a

solution.

room

D/W =

for

1

improvement on the market bubble outcome. For example,

— Q5 <

1,

then the government can opt for the sterilization

But, in contrast to the solution in the previous section, the sterilization leverages future

taxes and not current taxes.

^^This limit result

is

akin to the point

made

in

McCallum

(1987) and extended in Caballero and

Ventura (2002), that well defined property rights even over an infinitesimal share of an economy's

growing output, can eliminate the possibility of bubbles.

22

fully

crowd out the bubble.

When

=

p

the the government can only sterilize but

1,

is

unable to implement intergenerational redistributions without incurring risks similar

to those of the market bubble.

Remarks

Final

7

One view of emerging markets crises describes normal

times as periods with significant

capital inflows, which are suddenly interrupted by liquidity crises.'®

This paper highlights a different view. Normal times are those with net capital

outflows. These normal periods are occasionally interrupted by speculative bubbles,

many

Moreover, we show that in

which can crash.

instances these bubbles, while

rational, are socially inefficient since they introduce excessive aggregate fragility.

Both views stem from some form of

bubble-view

reflects a

financial

more primitive domestic

underdevelopment. However, the

financial market,

where residents

find

limited trust-worthy local assets.

Ingredients of both views probably coexist and vary in relative importance across

economies and times. During the mid 1990s,

large

amounts

of capital inflows,

and a crash

series of crises that started with

to the rest of the region,

in local bubbles.

example. South East Asia received

which financed both productive investments and fed

Real Estate bubbles. In this context, the

and soon spread

for

had elements of both a liquidity

Over time, the

bubble-assets were not recreated.

The

Thailand

latter

crisis

liquidity crunch disappeared, but the

phenomenon has played out

much

in

of the

Emerging Market world

^From

the point of view of our analysis, the disappearance of the bubble assets

as well as in

some newly industrialized economies.

important factor behind the acceleration of the capital inflows to the

US current account

the worsening of the

the same

its

lines, despite the

deficit- since the

savers are forbidden from accessing

may

Asian/Russian

crises.

an

hence

Along

attention that China's dollar-reserves accumulation and

potential reversal has received, the real danger

capital controls

US — and

is

US

may

lie

elsewhere. Today, Chinese

instruments directly.

A

normalization of

lead to a crash in their buoyant real estate market and increased

capital outflows toward the US.

It

goes without saying that ours

is

a highly stylized characterization of emerging

market dynamics. For practical purposes, we do not mean

'®E.g.,

Furman and

Stiglitz (1998),

to highlight the multiple

Calvo (1998), Caballero and Krishnamurthy (2001), Chang

and Velasco (2001).

23

equilibria nature of bubbles, or even the

extreme form of rationality we have required

on agents. They simply capture the high

volatility in

emerging markets and the

of speculation and expectations. Moreover, although the bursting of bubbles

nous in our model, one could extend

for instance,

it

and

link the

exoge-

bubble bursting to fundamentals;

any domestic or external factor that

raises the relative

eign assets, could crash the bubble in our model.

volatile

is

role

Bubbles

for

appeal of

for-

us represent highly

domestic financial assets which are not backed by solid fundamentals, sound

government

policy,

and

domestic markets, rich

institutions.

in

They have the

potential to yield high returns

if

funds but poor on quality assets, choose to speculate on

them, but they are also susceptible to large drops

24

if

fundamentals turn sour.

References

[1]

Abel, A.B., N.G. Mankiw, L. H.

Dynamic

Efficiency:

Summers and R.

J.

Zeckhauser, "Assessing

Theory and Evidence," Review of Economic

Studies, 56,

1989, pp. 1-20.

[2]

Bernanke, B., "Asset-Price Bubbles and Monetary Policy." Remarks before the

New York Chapter

October

[3]

NY, NY,

of the National Association for Business Economics,

15, 2002.

Blanchard, O.J. and M. Watson, "Bubbles, Rational Expectations and Financial

Markets," In P. Watchel (ed). Crises in the Economic and Financial Structure,

Lexington,

[4]

Bulow,

J.

MA. Lenxington

Books. 1982

and K. Rogoff, "A Constant Recontracting Model

of Sovereign Debt,"

Journal of Political Economy 97, February 1989, 155-178.

[5]

Caballero, R.J. and A. Krishnamurthy, "International and Domestic Collateral

Constraints in a Model of Emerging Market Crises," Journal of Monetary Eco-

nomics

[6]

48, 513-548, 2001.

Caballero, R.J. and A. Krishnamurthy, "Excessive Dollar Debt: Underinsurance

and Domestic Financial Underdevelopment," Journal of Finance

April, 58(2),

pp. 867-893, 2003.

[7]

Caballero, R.J. and A. Krishnamurthy,

tral

[8]

Bank

Interventions in Extreme Events,"

Caballero, R.J. and

J.

MIT Mimeo, November

[9]

[10]

of Flight to Quality

MIT mimeo, March

and Cen-

2005.

Ventura, "The Social Contrivance of Property Rights,"

2002.

Caballero, R.J., E. Farhi, and

the

"A Model

M.L.Hammour, "Speculative Growth: Hints from

US Economy," MIT Mimeo, May

Calvo, G.A., "Balance of

Payment

2004.

Crises in

Emerging Markets," mimeo, Mary-

land, January 1998.

[11]

Chang, R. and A. Velasco, "A Model

of Financial Crises in

Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 116, No. 2

25

,

May

Emerging Markets,'

2001.

[12]

Diamond,

P.,

"National Debt in a Neoclassical Growth Model," American Eco-

nomic. Review 55(5),

[13]

[15]

New

91, 1983, pp. 401-419.

Challenges for Monetary Policy,

Symposium

Volatility,"

Proceedings, Kansas City

Fed, 1999.

Furman,

Asia

[16]

Journal of Political Economy

Dornbusch, R., "Commentary: Monetary Policy and Asset Market

in

'

1965, 1126-1150.

Diamond, D.W. and P.H. Dybvig, "Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity,"

[14]

December

"

J.

and

J. Stiglitz,

"Economic

Evidence and Insights from East

Crises;

Brookings Papers of Economic Activity,

vol. 2 (1998), 1-114.

Hellwig, C. and G. Lorenzoni, "Bubbles and Private Liquidity,"

MIT

mimeo,

February 2003.

[17]

Holmstrom, Bengt and

Tirole, Jean, "Private

and Public Supply

Journal of Political Economy 106-1, February 1998, pp.

[18]

Jackhn, C.J.,

"Demand

of Liquidity,"

1-40.

Deposits, Trading Restrictions and Risk Sharing," in

Contractual Arrangements for Intertem.poral Trade, edited by E.Prescott and

N.Wallace. Minneapolis. U. of Minnesota Press, 1987.

[19]

McCallum, B. "The Optimal

omy with Land,

in

Rate

Inflation

New Approaches

to

K.J. Singleton Eds), 1987, Cambridge,

Money and

in

an Overlapping Generations Econ-

Monetary Economics (W.A. Barnett and

UK: Cambridge

m Economic

University Press.

[20]

McKinnon,

[21]

Samuelson, P.A., "An Exact Consumption Loan Model of Interest, with or with-

R.,

Capital

Development, Brookings 1973.

out the Social Contrivance of Money," Journal of Political

Economy

66(5), De-

cember 1958, 467-482.

[22]

Tirole, J. "Asset

November

[23]

1985, 1499-1528.

Saint-Paul, G. "Fiscal Policy in an Endogenous

nal of

[24]

Bubbles and Overlapping Generations," Econometrica 53(6),

Economics

Ventura,

J.

107, 4,

November

Growth Model," Quarterly Jour-

1992, 1243-59

"Bubbles and Capital Flows,"

26

CREI mimeo, January

2004.

[25]

Weil, Ph., "Confidence and the real Value of

Money

Models," Quarterly Journal of Economics 102,

27

^28^ 03!

1,

in

Overlapping Generation

Feb 1987, 1-22

Date Due

Lib-26-67

MIT LIBRARIES

"!ll"!||||||||||iiii|iin

3 9080 02618 2078

iWKslilD'vn'JiKWi::