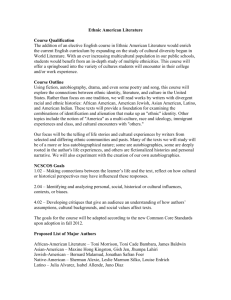

Commercial Revitalization in Union Square:

advertisement