36688. E-mail: . SERVICE-LEARNING PROJECT DISTRIBUTION IN THE DOG RIVER

advertisement

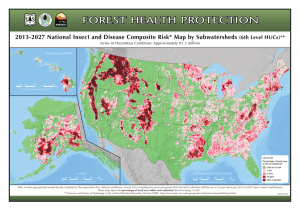

SERVICE-LEARNING PROJECT DISTRIBUTION IN THE DOG RIVER WATERSHED D. Logan Anderson, Department of Earth Sciences, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36688. E-mail: dla1001@jagmail.southalabama.edu. Service-learning at the undergraduate level helps to focus on “man-land” interactions and develop student research interests regarding the quality of watersheds throughout the United States. Such programs, with the cooperation of watershed maintenance organizations, provide a database of reports which comment on the health of local watersheds as well as provide support for communities interested in maintaining the quality of those watersheds. Because most undergraduate student-led watershed research projects must be completed within a traditional semester, there may be difficulty in designating a feasible topic due to the ever-increasing amount of former student projects. Such is the case at the University of South Alabama within the department of Earth Sciences. Geography students enrolled in their respective fieldwork course (GEO 480) compete with a variety of former, student-led research topics regarding their local watershed, the Dog River Watershed, spanning sixteen years. While some projects present the opportunity for temporal study, most seemingly inhibit the variability of future studies which can be accomplished within a given time frame. Therefore, the spatial distribution of former study areas and the frequency of former topics were compiled and mapped for the purpose of aiding future GEO 480 students to determine problems and potential maintenance goals unique to previously, less-researched study areas was the objective of this study. It was discovered that the most-researched topics concerned water quality and little to no research had been accomplished regarding terrestrial characteristics of the Dog River Watershed. Keyword: service-learning, undergraduate research, watershed Introduction Between eastern Texas and western Florida, coastal watersheds bordering the Gulf of Mexico provide important support systems for localized wetland areas as well as serve the needs of industrial transportation networks for inland economies (Zhang et. al., 2011). By understanding the complexities of watersheds and attributing their health and maintenance to sustaining the integrity of the environment (Haury, 2000), we can protect such resources as a means of supporting the future growth of human development. Much pollution on land and in water is watershed based, caused by numerous direct and indirect factors influenced by 1 interactions between the land and the people who inhabit it (Shepardson et. al., 2007); however, communities tend to be unknowledgeable of the repercussions of these interactions without the interests of watershed associations and the goals of service-learning initiatives which inspire the improvement of water quality and the protection of water resources (Cline et. al., 2003). Within the past ten years, efforts to reduce the effects urban growth have upon the ecosystem correlate negatively with provisions of urban ecosystem services (Schmidt et. al, 2012). Education is necessary, and the implementation of service-learning programs at the undergraduate college level have proven to help focus on “man-land” interactions through student discovery of potential solutions to issues associated with populated, urban watersheds. Doing so tends to bridge the gap between academic communities and public communities in terms of the levels of interest in preserving their local watershed (Elfin et. al., 2007). An example of such “bridge building” is the Thornton Creek Project near Seattle, Washington; the activities undertaken by students allowed for educational programs, restoration projects, and workshops to be administered at the community level after research had been done for course credit and presented as part of an overall service-learning project. The knowledge they gathered, be it from personal field observation and measurement or secondary research, helped to blur the lines between all community divisions and inspire continued monitoring of their local watershed (Donahue et. al., 1998). Similar community outreach is apparent in Mobile, AL through a grassroots organization known as the “Dog River Clearwater Revival” (DRCR), whose bylaws state: “The purpose of this organization is to improve the water quality in the streams, creeks, rivers and wetlands of the Dog River Watershed, and to restore and maintain the quality of life and best possible environment for fish and wildlife, public recreation, and commerce in the watershed. Dog River 2 Clearwater Revival encourages vigilant enforcement of environmental protection laws, the use of Best Management Practices (BMPs) and Best Available Technologies(BATs) in storm water and flood plain management, and general public education and outreach regarding responsible land use practices within the watershed” (Dog River Clearwater Revival, 2013). In addition to the efforts of the Dog River Clearwater Revival organization, students at the University of South Alabama, with the guidance of Dr. Miriam Fearn, Chair of the Department of Earth Science, “…study problems related to water quality in the Dog River Watershed” with the objective of “… [improving]…students’ research and writing skills, [applying] classroom knowledge to a real world problem, and [providing] information of value to the community” (Dog River Watershed, 2012). This is primarily done through field work, undertaken by students, and through the evaluation of student-led projects which ideally identify an issue they see threatening the health of a particular area of the watershed and potential ways to alleviate such threats. Studies in the field are excellent modes of integrating classroom content with practical concepts of research (Kent et. al, 1997). When incorporated as a means of encouraging projects such as watershed maintenance, a wealth of knowledge can emerge benefiting both the learning experience and the community, but “[t]he most difficult part of…fieldwork…for many students is the interpretation of their own results” (Haigh et. al., 1993). Being introduced to an overall appreciation of the study area and then being left to conduct “option-based” fieldwork can conflict with particular needs of the project as a whole (Kent et. al, 1997), which can be summarized as lacking in knowledge of certain areas of the project which have previously been un-researched yet need to be researched. In the case of the University of South Alabama, students undertaking personal field research to identify and offer potential suggestions of improving the Dog River Watershed and 3 its maintenance are faced with a seemingly bourgeoning database of knowledge as previous studies populate the list of projects. This will hinder further studies of the watershed by students with a limited time frame for project completion as the daunting task of creating a unique hypothesis becomes inundated with similar interests having already been researched. Without the ability to recognize where “holes” exist in the research regarding the maintenance of the Dog River Watershed, I feel it may become even more difficult to satisfy this lack of research, ultimately affecting watershed quality maintenance in the form of student involvement. By presenting an overall distribution of former projects, the areas of the Dog River Watershed which lack student research are spatially exposed, potentially aiding future fieldwork students with the ability to provide unique projects beneficial to the maintenance of the watershed. Research Question What is the spatial distribution of former study areas and which topics tend to be the most studied within the Dog River Watershed? Answering such questions concerning student-led research regarding issues and maintenance of the Dog River Watershed, future fieldwork students can determine problems and potential maintenance goals unique to previously, lessresearched study areas. Study Area The major and minor fluvial systems of Dog River drain a ninety-five square mile basin located near the northwestern side of Mobile Bay in southwest Alabama (Dog River Watershed, 2013) (Figure 1). The major municipality dependent upon this watershed is the city of Mobile, which lies approximately 140 miles east of the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, 72 miles west of 4 Pensacola, Florida, and 250 miles south of Birmingham, Alabama along the west bank of Mobile Bay near the mouth of the Mobile River. From 1997 to 2012 senior students enrolled in Dr. Miriam Fearn’s Fieldwork course, Geography 480, have chosen to research issues within, and pertaining to, the Dog River Watershed. Due to the nature of this study and the goal of determining the frequencies, trends and distribution of former projects completed by Fieldwork students over the course of sixteen (16) years, all data collected and analyzed was limited solely within the boundaries of the watershed. Figure 1 THE DOG RIVER WATERSHED AND ITS PROXIMITY TO MOBILE, AL, MOBILE BAY AND THE GULF OF MEXICO. Sources: ESRI; City of Mobile, AL 5 Methods Data pertaining to this project was collected and analyzed in three stages. The first of these being archival research, performed similarly to the method performed by Dr. Carol Sawyer in her participation of documenting avalanche frequency in Columbia Falls, Montana between 1946 and 2005 (Sawyer et. al., 2006). Information was compiled using research reports collected by Dr. Fearn in the department of Earth Science detailing former student research conducted in the Dog River Watershed. To organize student reports for subsequent categorization, the year it was written, associated key words and titles of each project were hand recorded into a log with a corresponding number. For example, the key words of the first project, the year it was written, its author, and its title were given the number (1), and the same criteria for the second project were given the number (2), and so on and so forth (Appendix A). A total of 191 student reports were recorded. Once this had been accomplished, using Microsoft Excel, key words following abstracts of each student report were entered. Although some reports failed to utilize key words following an abstract, a majority of projects contributed to the 539 total key words recorded and alphabetized for further organization. After double checking each key word against their corresponding abstract, all similar key words were combined into a single Microsoft Excel column to represent the numerical total of any word used more than once (Appendix B). This was a necessary step due to a desire to provide initial data for analysis regarding project topics at their most fundamental level. However, in order for students enrolled in future Fieldwork classes to benefit from this list of key words, they would need to be able to associate each key word with a project which they could further, independently investigate. Therefore, using the first data log of this project, each project report number was recorded next to its respective key word in the 6 combined key word list to show a return of which projects utilized which key word (Appendix C). As an example, the key word “Awareness” was used twice by projects numbered 5 and 39. The second stage of data collection and analysis for this project relied on a method of organizing published research into various categories, completed by Dr. Carol Sawyer in her unpublished doctoral dissertation wherein patterned ground research was sorted by form (Sawyer, 2007). Because the majority of student Fieldwork reports deal with the physical characteristics of a watershed, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s “Watershed Condition Indicator Model” was used in an attempt to classify each report (Potyonde et. al., 2011). Although such a model of classification is used to determine the health of a watershed, in the case of this project it was accessed as a means of organizing student topics. The four initial Watershed Condition Indicator categories are “Aquatic Physical,” “Aquatic Biological,” “Terrestrial Physical,” and “Terrestrial Biological.” Again, because the purpose of this project is not to determine the health of a watershed, a fifth category was added to absorb student topics which fall outside of the EPA’s watershed health indicators, and is simply titled “Other.” Within each of the four initial Condition Indicator Categories and within the added “Other” category is an additional seventeen (17) Watershed Condition Indicators suitable for further categorizing student reports: (1) Water Quality, (2) Water Quantity, (3) Aquatic Habitat, (4) Aquatic Biota, (5) Riparian/Wetland Vegetation, (6) Roads and Trails, (7) Soils, (8) Fire Regime or Wildlife, (9) Forest Cover, (10) Rangeland Vegetation, (11) Terrestrial Invasive Species, (12) Forest Health, (13) Public Education, (14) Historical Perceptions, (15) Social Characteristics, and (17) Atmospheric Characteristics (Table 1). 7 Table 1 WATERSHED CONDITION INDICATOR DESCRIPTIONS. Aquatic Physical Indicators 1. Water Quality 2. Water Quantity 3. Aquatic Habitat This indicator addresses the expressed alteration of physical, chemical, and biological components of water quality. This indicator addresses changes to the natural flow regime with respect to the magnitude, duration, or timing of the natural stream flow hydrograph. This indicator addresses aquatic habitat condition with respect to habitat fragmentation, large woody debris, and channel shape and function. Aquatic Biological Indicators 4. Aquatic Biota This indicator addresses the distribution, structure, and density of native and introduced aquatic fauna. 5. Riparian/Wetland Vegetation This indicator addresses the function and condition of riparian vegetation along streams, water bodies, and wetlands. Terrestrial Physical Indicators 6. Roads and Trails 7. Soils This indicator addresses changes to the hydrological and sediment regimes because of the density, location, distribution, and maintenance of the road and trail network. This indicator addresses alteration to natural soil condition, including productivity, erosion, and chemical contamination. Terrestrial Biological Indicators 8. Fire Regime or Wildlife 9. Forest Cover 10. Rangeland Vegetation 11. Terrestrial Invasive Species 12. Forest Health This indicator addresses the potential for altered hydrologic and sediment regimes because of departures from historical ranges of variability in vegetation, fuel composition, fire frequency, fire severity, and fire pattern. This indicator addresses the potential for altered hydrologic and sediment regimes because of the loss of forest cover on forest lands. This indicator addresses effects on soil and water because of the vegetative health of rangelands. This indicator addresses potential effects on soil, vegetation, and water resources because of terrestrial invasive species (including vertebrates, invertebrates, and plants). This indicator addresses forest mortality effects on hydrologic and soil function because of major invasive and native forest insect and disease outbreaks and air pollution. Other 13. Public Education Projects related to public awareness and education of local watersheds. 14. Policy Projects related to laws governing man-land interactions with local watersheds. 15. Historical Perceptions Projects related to the history and evolution of local watersheds. 16. Social Characteristics Projects related to populations which affect local watersheds. 17. Atmospheric Characteristics Projects related to how atmospheric conditions are within local watersheds. 8 By examining each report, its topic, and its key word(s), project report numbers were assigned to each of the Watershed Condition Indicators. Another Microsoft Excel table was produced to represent the quantities of reports under their respective categories, reflected in the occurrences of each individual project report number (Table 2). Table 2 STUDENT REPORTS ORGANIZED WITHIN THE WATERSHED CONDITION INDICATOR CATEGORIES. Watershed Condition Indicators Categories Corresponding Student Reports (By Number) Water Quality 3, 4, 13, 14, 18, 22, 30, 31, 35, 36, 38, 40, 41, 43, 45, 48, 50, 51, 54, 55, 59, 66, 69, 72, 74, 79, 82, 83, 84, 90, 92, 97, 101, 103, 104, 109, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 122, 123, 125, 127, 128, 131, 134, 138, 140, 145, 149, 151, 152, 158, 162, 166, 167, 168, 169, 174, 178, 181, 184, 185, 186, 187 Water Quantity 19, 21, 37, 47, 53, 61, 62, 69, 86, 94, 95, 109, 135, 143, 147, 150, 161, 175 Aquatic Habitat 10, 11, 29, 34, 49, 52, 67, 71, 91, 106, 111, 139, 164, 180 Aquatic Biota 28, 63, 73, 110, 170, 171 Riparian/Wetland Vegetation 2, 24, 32, 42, 56, 78, 80, 88, 89, 98, 144, 154, 142 Aquatic Physical Indicators Aquatic Biological Indicators Terrestrial Physical Indicators Terrestrial Biological Indicators Roads and Trails Soils Fire Regime or Wildlife Forest Cover Rangeland Vegetation Terrestrial Invasive Species Forest Health Public Education Policy Other Indicators 156, 159 65, 87, 96, 102, 105, 108, 112, 153, 155, 163, 172, 173, 177, 182 6 5, 15, 22, 25, 39, 60, 64, 75, 77, 121, 124, 129, 141, 146, 126 23, 46, 57, 99, 130 Historical Perceptions Social Characteristics Atmospheric Characteristics 9 1, 7, 8, 9, 12, 16, 17, 26, 27, 85, 107, 133, 136, 148, 179, 176, 189 70, 90, 93, 113, 137, 157 44, 165, 191 65, 100, 120, 132, 163, 183, 188, 190 160 The final stage of data collection and analysis dealt solely with the distribution of former student project study areas. Using ArcMap software, version 10.1, two field maps were created, similar to Figure 1, of the Dog River Watershed with an added water bodies layer and road network layer. In re-examining each of the 191 student reports, points were placed, by hand, on a printed copy of the field maps. Visual approximations of study sites were made with student reports whose study area descriptions did not give exact locations, exact locations were marked with student reports whose study area descriptions included geographic coordinates, and any studies completed of the entire watershed or large sections of the watershed were designated as “Difficult to Determine.” Student reports which did not specify a study area, such as those belonging to the “Historical Perceptions” indicator category, or were beyond the boundaries of the Dog River Watershed were designated as “No Study Site Specified” or “Outside Watershed.” After all points were recorded on the field maps, methods outlined in Wagner’s article regarding the spatial distribution of archaeological sites in northern China (Wagner et. al, 2013) guided the digital input of each study site location into a shape file within ArcMap to show their spatial distribution throughout the Dog River Watershed (Figure 2). Afterwards, using ArcToolbox spatial analyst software, each study area was rasterized for the density of student research completed at that particular location (Figure 3) and a “mask” was created to confine all raster values within the borders of the Dog River Watershed for visual purposes. 10 Figure 2 FORMER STUDENT RESEARCH REPORT STUDY SITES WITHIN THE DOG RIVER WATERSHED Figure 3 INITIAL DESNITY RASTER OF FORMER STUDENT RESEARCH REPORTS 11 Results After recording 539 key words from the abstracts of student project reports in Geography 480, Fieldwork, and grouping them based on the frequency of their usage, a “Top Twenty” list was compiled which displays the greatest occurrences of the following key words: Dog River, Water Quality, Dog River Watershed, Turbidity, Watershed, Litter, Sedimentation, Channelization, Mobile, Runoff, Alabama, Sediment, Urbanization, Wetlands, Best Management Practices (BMPs), Trash, Construction, Dissolved Oxygen, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and Spring Creek (Figure 4). Each of these key words occurs five times or greater among the total amount of key words selected by students. Besides common key words associated with a majority of reports, such as “Dog River,” or “Dog River Watershed,” all key words are associated with projects which exhibit the greater frequencies regarding their organization within the Watershed Indicator Model. Top Twenty Key Words 40 35 Number of Occurrences 30 25 20 38 15 10 20 19 18 15 5 11 10 8 8 8 7 7 7 7 0 Key Words Figure 4 KEY WORDS USED FIVE TIMES OR GREATER 12 6 6 5 5 5 5 Regarding the organization of student project reports into categories outlined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Watershed Condition Indicator Model, as well as the addition of an “Other Indicators” category, projects concerned with the sub-category “Water Quality” were the most common with 67 reports (Figure 5). Sub-categories with a number of student reports greater than 10 but less than 20 were “Water Quantity,” “Roads and Trails,” “Public Education,” “Aquatic Habitat,” “Rangeland Vegetation,” and “Riparian/Wetland Vegetation.” Sub-categories with a number of student reports greater than one but less than 10 were “Social Characteristics,” “Aquatic Biota,” “Soils,” “Policy,” “Historical Perceptions,” “Forest Cover,” “Terrestrial Invasive Species,” and “Atmospheric Characteristics.” The final two sub-categories had no comparable student reports and were “Fire Regime or Wildlife,” and “Forest Health.” Watershed Condition Indicators 80 Number of Corresponding Student Reports 70 60 50 40 67 30 20 10 18 17 15 14 14 13 8 6 6 4 3 2 1 1 0 Condition Indicator Categories Figure 5 FREQUENCY OF STUDENT REPORTS WITHIN SUB-CATEGORIES OF THE WATERSHED CONDITION INDICATOR MODEL 13 0 0 The distribution of former student research report study areas within the boundaries of the Dog River Watershed exhibit high densities in or around areas of the “Halls Mill Creek,” “Moore Creek,” “Eslava Creek,” and “Rabbit Creek” sub-watersheds. The total number of study sites, with the exception of those concerning the entire Dog River Watershed, undisclosed or difficult to determine study sites, or reports not dealing with physical aspects of the watershed, was 445. Visually these densities are represented with the help of a density raster wherein the greater the amount of student report study areas within an area, the higher the raster value. Subsequently, these higher densities appear as a darker color within the map in Figure 6. Figure 6 FINAL DENSITY RASTER OF FORMER STUDENT REPORTS. NOTE THE DARKER SHADES OF GREEN REPRESENTATIVE OF THE LOCATION OF GREATER NUMBERS OF FORMER STUDY AREAS. 14 Discussion and Conclusion In analyzing the extracted data regarding written student reports between the years 1997 and 2012 and distributing them among the four major Watershed Condition Indicators, as outlined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, several factors were taken into consideration. First, with an initial twelve sub-categories within the Watershed Condition Indicators, it was important to understand how each student project applied to the description of these indicators. Many projects were difficult to define in terms of an indicator due to the fact that their study seemingly dealt with more than one issue concerning the Dog River Watershed. It often became necessary to further interpret the project based on the author’s research questions and objectives and how they applied to their results. As obvious as such a task may seem, it was not apparent that this particular way of determining the best category for a project was the most suitable method until these two aspects of the projects were separated from the rest of the research. After this was accomplished, an additional issue occurred in the interpretation of reports and their categorizations, which were those projects that, in little to no way, met the qualifications of the Watershed Condition Indicator category descriptions. By adding a new category to satisfy such projects, new sub-categories presented themselves due to the frequency in which the reports satisfied various other topic descriptions. Second, with so many topics previously studied, determining the importance of categorizing them and recognizing their trends and the spatial distribution of each study area was key to understanding in which ways this data could be presented to provide the best possible resource for future Fieldwork students trying to develop their own unique research perspective. Given the results it is apparent that a majority of students have always been concerned with the quality of water within the Dog River Watershed, which is in and of itself a great resource for 15 those interested in the maintenance of the watershed. However, what we see as a result of this study is the need for greater interest in other areas of the conditions of the Dog River Watershed, particularly those of a terrestrial nature. This is also evident in the highest densities of study areas being centered on the aforementioned sub-watersheds and the lowest densities spread out among the non-fluvial regions of the watershed. Finally, we have been made aware through these student reports the condition of the water itself, but what about some of the many factors influencing those conditions? Of course studies have been performed regarding the effects of impermeable surfaces, and the effects of urbanization, etc., but perhaps a new perspective on not just what negatively affects the water quality can be adopted. Some of the more creative topics dealt primarily with the habitat the Dog River Watershed provides; not just for plants and animals, but for humans as well. The social characteristics of what impacts the maintenance of watershed quality is of particular importance when we take into consideration the daily interaction humans have with the watershed that supports them. Overall, many of the reports generated by previous students in Dr. Fearn’s Geography 480, Fieldwork course provided generous insight into the workings of the Dog River Watershed, and on various levels. While this study aimed to provide a foundation for future Fieldwork students to recognize where more investigation is needed to understand and implement research concerning the quality of the watershed, it also provides an opportunity for further interpretation of its results. We know where the “holes” in student research topics exist, it is now important to understand why and any particular events or attitudes which may have influenced such trends. 16 Works Cited Cline, Sarah A., and Alan R. Collins, (2003). Watershed associations in West Virginia: their impact on environmental protection. Journal of Environmental Management. 67, pp. 373383. Dog River Clearwater Revival [online]. (2013). Available from: <http://dogriver.org/our-urbanwatershed>. [Accessed 25 February 2013]. Dog River Watershed [online]. (2012). Available from: <http://dogriver.southalabama.edu>. [Accessed 03 February 2013]. Donahue, Timothy P., Lisa Bryce Lewis, Lawrence F. Price, and David C Schmidt, (1998). Bringing science to life through community-based watershed education. Journal of Science Education and Technology. 7, pp. 15-23. Elfin, James, and Amy L. Sheaffer, (2007). Service-learning in watershed-based initiatives: keys to education for sustainability in geography? Journal of Geography. 105, pp. 33-44. Haury, D.L., (2000). Watersheds: a confluence of important ideas. Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse for Science Mathematics and Environmental Education. Kent, Martin, David D. Gilbertson, and Chris O. Hunt, (1997). Fieldwork in geography teaching: a critical review of the literature and approaches. Journal of Geography in Higher Education. 21, pp. 313-332. Sawyer, Carol F. (2007). Frost heaving and surface clast movement in turf-banked terraces, Eastern Glacier National Park, Montana. ETD Collection for Texas State University. https://digital.library.txstate.edu/handle/10877/4295. Sawyer, Carol F., and David R. Butler, (2006). A chronology of high-magnitude snow avalanches reconstructed from archived newspapers. Disaster Prevention and Management. 15, pp. 313-324. Schmidt, P., and T.H. Morrison, (2012). Watershed management in an urban setting: process, scale and administration. Land Use Policy. 29, pp. 45-52. Shepardson, Daniel P., Bryan Wee, Michelle Priddy, Lauren Schellenberger, Jon Harbor, (2007). What is a watershed? Implications of student conceptions for environmental science education and the national science education standards. Science Education. 91, pp. 554578. Potyonde, John P. and Theodore W. Geier (2011). Watershed condition classification technical guide. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture. pp. 5-6. 17 Wagner, Mayke, Pavel Tarasov, Dominic Hosner, Andreas Fleck, Richard Ehrich, Xiaocheng Chen, Christian Leipe, (2013). Mapping of the spatial and temporal distributon of archaeological sites of northern China during the neolithic and bronze age. Quaternary International. 290-291, pp. 344-357. Zhang, N., Z.C. Zheng, and Saikiran Yadagiri, (2011). A hydrodynamic simulation for the circulation and transport in coastal watersheds. Computers and Fluids. 47, pp. 178-188. 18