LITTER: DIFFERENCES BETWEEN DIRT ROADS WITH OR WITHOUT DWELLINGS

advertisement

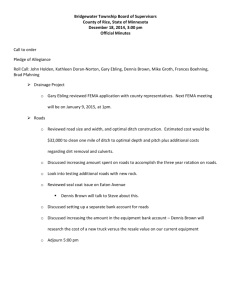

LITTER: DIFFERENCES BETWEEN DIRT ROADS WITH OR WITHOUT DWELLINGS Christopher W. Taylor, Department of Earth Sciences, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36688. E-mail: cwt1001@jagmail.southalabama.edu. In this paper I find differences between illegal trash dumping on dirt roads with dwellings compared to dirt roads without dwellings. I researched all dirt roads in the Rabbit Creek area by using Google Earth. I then qualified each road into two categories. First I measured the length of the road, then I researched the number of dwellings which can only be accessed by that road. After this information was compiled the number of dwellings was divided by the length of the road in miles to give an average number of dewllings per mile for each dirt road. The roads were then separated into two categories; 1) dirt roads with less than three dwellings per mile, 2) dirt roads with three or more dwellings per mile. I compiled both lists of roads and randomly picked two roads out of each category and visited each to view the trash or litter. For the purposes of this project I classified illegal dumping as a single piece of debris weighing at least five pounds or a pile of debris measuring one cubic yard or more. These roads were then inspected and I concluded that the dirt roads with three or less dwellings on them had a significantly larger amount of illegal dumping than dirt roads with three or more dwellings. Keywords: Illegal dumping, dirt road, litter Introduction: Littering and illegal trash dumping has become a major issue not only in the Dog River Watershed but all over the country. Illegal dumping of hazardous and non hazardous materials is now far too common. In a recent article on landlinemag.com, Greg Grisalono reported that Black Hills Trucking Inc. based out of Wyoming was facing a fine of $1 million dollars and one of their drivers was going to be criminally charged for an illegal dumping incident. This company hauls saltwater and other liquid drilling waste from the drill rigs to an accepted dump site. Apparently the driver with his company's knowledge was travelling through a rural area gravel road with his valves purposely open in order to discharge the truck's waste on a regular basis. Luckily for the county in which this was taking place, an inspector with the Department of Mineral Resources witnessed one of these incidents and immediately stopped it (Grisolano, 2014). My research is not focused on the obvious hazardous waste illegal dumping from businesses but more on the average pickup truck you see driving down the road with various amounts of garbage and debris in the bed of the truck. Unfortunately, it is naive to think that everyone with a pickup truck full of garbage is going to dispose of it legally. This research is also not focused inside the city limits where it is a common practice to pile trash and debris by roadsides for a tax subsidized trash pickup. Instead it is focused on unpaved roads outside the city limits where there is no organized trash pickup system in place. These locations are usually remote so that these criminals can easily dump their goods without suspicion. The illegally dumped material can consist of anything from a simple piece of trash to larger materials such as household garbage, typical lawn and garden debris, furniture, vehicles and in some cases extremely hazardous materials. The real problem arises after the first dumping of trash has taken place, the location then practically becomes a breeding ground for others with wastes they would like to dispose of (U.S. Dept. of Interior BLM, 2009). Dirt roads have become a favorite place for these illegal dumpers, especially dirt roads with little to no dwellings on them. Depending on how you look at it, these roads are literally too good or bad to pass up. Many people don't think twice about littering. How many times have you seen someone throw a cigarette out of a vehicle, or perhaps even done it yourself. It seems insignificant at the time but people need to see the bigger picture when it comes to any kind of litter. Any type of toxin for instance a small amount of used motor oil can be deadly. Animals suffer everyday from large pieces of litter such as getting tangled in it or ingesting it, but small amounts can be just as dangerous. Plant life can also suffer at the hands of litter. Litter can manipulate both physical growth and chemical makeup of plant life (Amatangelo, 2008). In the example of the small amount of motor oil, it can enter a watershed in drops but can be concentrated by biomagnifications. This basically means the toxin once consumed by the smallest of organisms will be magnified ten times per each step of the food chain (Kilgore, 1999). By the time a fish is eaten by a human the levels of toxins originally released by the small drop of oil could be very hazardous to their health. By driving along some of these dirt roads, I noticed a glaring problem in the Dog River Watershed. The dirt portion of Rabbit Creek Dr. in Theodore had become an illegal dumping ground (Figure 1). This portion of road was no more than 100 yards from a tributary that fed into Rabbit Creek which ultimately flows into Dog River. It also only has 1 house near it which isn't visible from the road but can be accessed by it. By looking at Google Earth you can clearly see this same house is also accessed from another road to its east. This road was the inspiration for the idea of this project. I decided to find out if there was a difference in the amount of illegally dumped items on an unpaved road that had dwellings versus an unpaved road that had little to no dwellings. Figure 1: Illegal dumping on Rabbit Creek Dr. According to the book Reducing Litter on Roadsides by Gerry John Forbes, there is a jurisdiction in California that has distinguished littering into two forms. The forms are normal littering which carries the usual fine and what California considers to be criminal littering. To create a charge which falls into the criminal littering category, the state had to set up some parameters. The parameter is anything that is illegally dumped that weighs more than five pounds shows premeditation and will be hit with a steeper fine (Forbes, 2009). Research Question: Is there a greater or lesser amount of litter and illegal dumping on dirt roads with dwellings than dirt roads with few to no dwellings? Methods: I researched unpaved roads in the Rabbit Creek area by using ArcMap and Google Earth. I downloaded various GIS layers from the City of Mobile website including Roads and Water bodies. By utilizing ArcMap I created a center point between Rattlesnake Bayou and Rabbit Creek. As seen in Figure 2, I created a buffer zone around the center point for two miles. From there I clipped all roads inside the two mile buffer zone in order to limit my study area. Figure 2: 2 Mile buffer zone around Rabbit Creek Neal Howard, a supervisor at Mobile County Road and Bridge loaned me a book called County Maintained Road Inventory Report. I was able to use this book which gave road names and the length in feet of each road that was paved and/or unpaved. I compared this list to the clipped roads inside the buffer zone and was able to separate them into two categories; paved roads and unpaved roads in the zone. I also verified this information visually by using Google Earth. After compiling this information I then measured all unpaved roads with the measuring tool on ArcMap and counted the number of dwellings which can only be accessed by that road using Google Earth. Then I divided the number of dwellings by the length of the road in miles to give an average number of dwellings per mile for each unpaved road. I separated the roads into two categories; 1) dirt roads with less than three dwellings per mile, 2)dirt roads with three or more dwellings per mile. I chose two roads from each category to inspect the amount of illegally dumped materials. For the purposes of this project I classified illegal dumping as a single piece of debris weighing at least five pounds or a pile of debris measuring 1 cubic yard or more. I visited each road and recorded the actual amount of debris in units and calculated the amount of units it would be per mile. All four roads chosen were less than one mile so the entire length of road was inspected. A map made through ArcMap (Figure 3) shows all four locations. I created a table and bar graph to show any differences between the two roads with dwellings and the two roads without dwellings. Figure 3: Roads chosen for inspection highlighted Results: My research of the buffer zone shows a total of 220 roads inside the zone. The number of paved roads were 209 which left 11 unpaved roads in the zone for me to choose from. Table 1 shows all eleven roads along with the length and number of dwellings. I also calculated the average number of dwellings per mile and it is shown in that order in the table. ROAD NAME MILES Kooiman Side Rd Old Rangeline Side Rd Rabbit Creek Dr S Todd Acres Side Rd Todd Acres Dr Jackson Ln Bowden Cir Hobart Rd Shipyard Rd Juniper Ave Powell Ln 0.31 1.01 1.14 0.15 2.75 0.53 0.10 0.10 0.57 0.12 0.29 NUMBER OF DWELLINGS DWELLINGS PER/MILE 0 0 0 0 4 5 1 1 6 2 9 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 1.45 9.43 10.00 10.00 10.53 16.67 31.03 Table 1: List of unpaved roads dwellings per/mile As you can see there were a total of five unpaved roads meeting the criteria of less than three dwellings per mile, while there were six unpaved roads in the zone with an average of three or more dwellings per mile. The two roads chosen to inspect out of the greater than three dwellings were Shipyard Rd. and Powell Ln. The two roads from the less than three dwellings were Todd Acres Side Rd. and Kooiman Side Rd. I recorded the actual amount of debris which fell into my definition of illegal dumping for each road and calculated the amount it would be if the road was one mile long. The results are shown in Table 2. Length in Miles Dwellings Per/Mile Actual Units of Debris Units of Debris Per/Mile Todd Acres Side Rd 0.15 0.00 53 353.33 Kooiman Side Rd 0.31 0.00 86 277.42 Shipyard Rd N 0.57 10.53 2 3.51 Powell Ln 0.29 31.03 0 0.00 Name of Road Table 2: Amount of debris per/mile for two roads from each category The table indicate that it looks like the number of dwellings, or lack thereof, has a drastic effect on the amount of debris illegally dumped on unpaved roads. You can also see the difference in the pictures taken from each location which are labeled Figure 4a, 4b, 4c and 4d. Figure 4a: Powell Ln. Figure 4b: Shipyard Rd. Figure 4c: Todd Acres Side Rd. Figure 4d: Kooiman Side Rd. Conclusion: As mentioned earlier the inspiration for this project was born when travelling down Rabbit Creek Dr. and seeing the massive amount of debris less than 100 yards from a tributary leading to Rabbit Creek and ultimately Dog River. I wanted to prove that if these type of roads did not have people living on them, then the county should close them in order to stop the illegal dumping that occurs there. Looking back at the Figure 1 photo you can clearly see a couch among the debris pictured on Rabbit Creek Dr. By coincidence I ventured back to this road while researching the other four roads in order to take a better picture of the couch and others just to find that not only was the road now closed and blockaded (Figure 5) but the entire length of the road had been cleaned up with no debris to be found. Figure 5: Rabbit Creek Dr. After I am not naive enough to think that all illegal dumping can be stopped in the Dog River Watershed, however I think more steps can be taken to close down roads with no dwellings on them just like Rabbit Creek Dr. By doing this it would make it harder for people who want to dump their debris illegally because the more secluded places would be taken away. References: Amatangelo, K.L., Dukes, J.S. & Field, C.B. 2008. Responses of a California annual grassland to litter manipulation. Journal of Vegetation Science 19: 605–612. Forbes, G. J. (2009). Reducing Litter on Roadsides. Washington, D.C.: National Cooperative Highway Research Program. Grisolano, G. (2014, April 16). Wyoming trucking company faces $1 million fine for alleged illegal dumping. Land Line Magazine. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.landlinemag.com/Story.aspx?StoryID=26879#.U1ByS_ldUxA Kilgore, M. (1999) Litter and Pollution. Chintimini Wildlife Rehabilitation Center. Retrieved from http://www.chintiminiwildlife.org/Education/LivingWithWild/Litter.htm U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. (2009). Solid waste & illegal dumps. Retrieved from website: http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/more/hazardous_materials0/solid_waste___illegal.ht ml