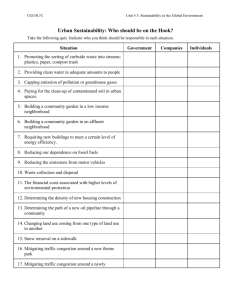

Citizen Implementation of Sustainability Measures til 1 6 If

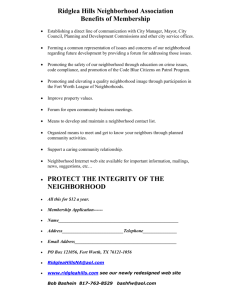

advertisement