& Community Development E. Bachelor of Arts

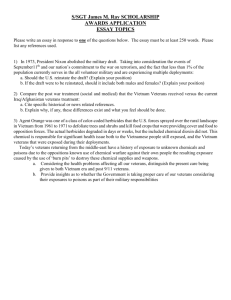

advertisement