LEARNING: Charles L. Forbes 1990 Connecticut College

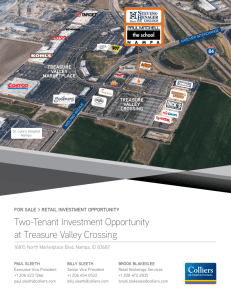

advertisement