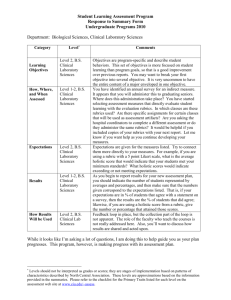

Report of the CUNY Task Force On System-Wide Assessment

advertisement