Rehousing Homeless Families in Massachusetts:

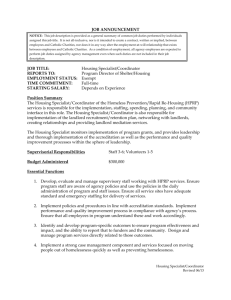

advertisement