Breaking Down Barriers, Building Up Communities:

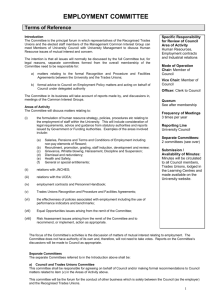

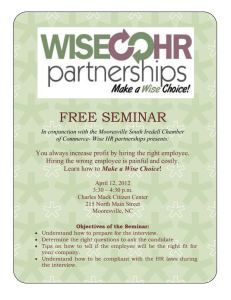

advertisement