A

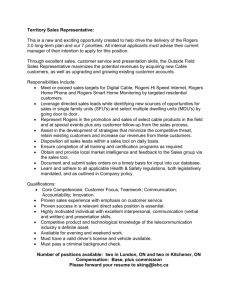

advertisement