RETHINKING HOMEOWNERSHIP:

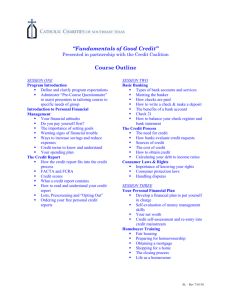

advertisement