Identifying Women’s Occupational Patterns in a Long-Term National Health Study

advertisement

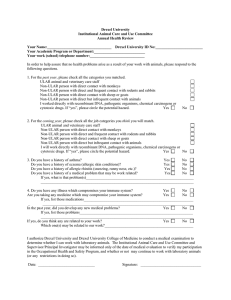

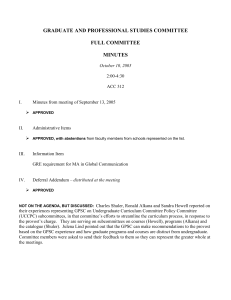

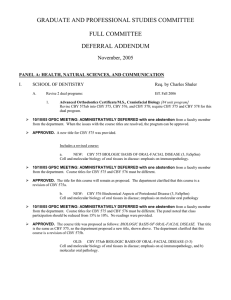

Identifying Women’s Occupational Patterns in a Long-Term National Health Study Aimee Palumbo, MPH1, Yvonne Michael, ScD1, Anneclaire De Roos, PhD1, Lucy Robinson, PhD1, Jana Mossey, PhD1, Carolyn Cannuscio, ScD2, Robert Wallace, MD3 1 Drexel University School of Public Health, 2 University of Pennsylvania Section on Public Health, 3 University of Iowa College of Public Health • Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS): long-term national cohort of postmenopausal women 50-79 years enrolled between 1994 and 1998 (n=93,605) • Occupational history: 3 longest-held jobs since age 18 • Women provided occupational title, industry, age started job, and years in job as well as age at first and last child • LCA conducted in MPlus v7 using job start and end ages, total years worked, total years between jobs, total number of jobs, and age at first and last child Results • 85,491 women worked at least one job since age 18 included • LCA identified 4 distinct patterns of work: (1) jobs of short duration early in adulthood, (2) working continuously, (3) intermittent jobs, and (4) later life jobs • Largest percent (40%) of women were categorized as working continuously since age 18 (Class 2) • Class 2 women were younger at study entry, had more education, and fewer children than women in other classes • Only 8% of women were categorized as working short, intermittent jobs early in adulthood (Class 1) • Women in Class 1 were more frequently older, married, and have high family income; these women were also more likely to be nondrinkers and to have never smoked • Women whose longest held jobs were held later in life (Class 4), were more likely to have low family income and to be divorced/ separated • No substantial differences in exercise frequency observed between classes (data not shown) • Women in Class 3 were slightly more likely to engage in light or moderate drinking, while women in Class 1 were slightly more likely to drink 7 or more drinks per week but also to abstain from drinking Table 1. Model Fit Statistics Model Classes Loglikelihood AIC Entropy 1 2 3 4 2 3 4 5 -­‐3073773.673 -­‐3022277.806 -­‐2957227.405 -­‐2927093.356 6147621.345 6044655.611 5914580.811 5854338.712 0.855 0.892 0.929 0.910 Mean (Std Dev) Age at study entry 65.8 (7.5) BMI at age 18 (n=84,023) 20.5 (2.9) BMI at study entry 26.7 (5.8) N (column %) Educa0on* (n=84,848) Less than high school 507 (7.7) High school 3691 (56.1) College degree or higher 2384 (36.2) Income* (n=81,949) Less than 35,000 2109 (33.8) 35,000 -­‐ 74,999 2109 (33.8) 75,000 + 1664 (26.7) Unknown 361 (5.8) Marital status* (n=85,126) Never married 80 (1.2) Divorced/separated 345 (5.2) Widowed 1190 (18.0) Married/marriage-­‐like rel. 4993 (75.5) Birth Region* (n=84,887) Northeast 1742 (26.5) Midwest 1901 (28.9) South 1469 (22.3) West 922 (14.0) Outside of US 542 (8.2) Work status* Working at baseline 0 (0) Recently re6red (<10 years) 66 (1.0) Re6red >10 years 6572 (99.0) Alcohol consump0on* (n=85,059) Non-­‐drinker 876 (13.3) Past drinker 1219 (18.5) Light to moderate drinking 3504 (53.1) 7+ drinks/week 1005 (15.2) Smoking status* (n=84,499) Never smoked 3469 (53.1) Former smoker 2723 (41.7) Current smoker 346 (5.3) Number of live births* (n=85,048) Never pregnant 424 (6.4) 0 or 1 705 (10.7) 2 -­‐ 4 4473 (67.9) 5+ 984 (14.9) Class 2 Worked con6nuously N = 34,000 (39.8%) 62.3 (73) 20.7 (3.1) 27.4 (6.0) Class 3 Class 4 Intermi:ent Later work N = 20,799 N = 24,054 (24.3%) (28.1%) 64.6 (7.1) 20.5 (2.7) 26.8 (5.5) 63.7 (7.2) 20.6 (2.9) 27.3 (5.8) 1247 (3.7) 16160 (47.9) 16330 (48.4) 598 (2.9) 1304 (5.5) 11111 (53.8) 13667 (57.2) 8944 (43.3) 8905 (37.3) 10765 (32.9) 14115 (43.2) 7011 (21.4) 808 (2.5) 7266 (36.5) 10319 (44.7) 7894 (39.7) 8437 (36.5) 4177 (21.0) 3765 (16.3) 561 (2.8) 588 (2.5) 3015 (8.9) 5769 (17.1) 5168 (15.3) 19243 (56.9) 206 (1.0) 721 (3.0) 2439 (11.8) 4808 (20.1) 3674 (17.7) 4393 (18.3) 14161 (68.3) 13565 (56.6) 8796 (26.1) 9518 (28.2) 8300 (24.6) 4834 (14.3) 2305 (6.8) 6554 (31.7) 6788 (32.8) 3441 (16.6) 2705 (13.1) 1221 (5.9) 6877 (28.8) 7068 (29.6) 4909 (20.6) 3214 (13.5) 1781 (7.5) 15642 (46.0) 12552 (36.9) 5806 (17.1) 7927 (38.1) 12508 (52.0) 7916 (38.1) 8154 (33.9) 4956 (23.8) 3392 (14.1) 3776 (11.2) 6287 (18.6) 19560 (57.8) 4220 (12.5) 1910 (9.2) 2481 (10.4) 3355 (16.2) 4764 (19.9) 12568 (60.7) 13781 (57.7) 2873 (13.9) 2880 (12.1) 17225 (51.3) 14104 (42.0) 2273 (6.8) 10558 (51.3) 11467 (48.3) 9043 (43.9) 10757 (45.3) 991 (4.8) 1543 (6.5) 5832 (17.2) 5873 (17.4) 19800 (58.5) 2332 (6.9) 892 (4.3) 1475 (6.2) 1688 (8.2) 2236 (9.4) 15059 (72.7) 16566 (69.3) 3063 (14.8) 3646 (15.2) *Characteristics differ significantly (p<0.05) by work pattern class 4 Characteris0cs Class 1 Short, brief, early jobs N = 6,638 (7.8%) Figure 1. Average ages and years at 3 longest-held jobs and childbearing years 3 Table 2. Demographic characteristics of study population by pattern of work 2 Methods Results Class, Job, and Childbearing Years (CBY) • Steady employment predicts slower declines in health • Women are more likely to have intermittent work force participation throughout the life course compared to men • Longitudinal studies describing women’s work patterns are limited • Objective: To identify patterns of work, or time in and out of the workforce, in women using Latent Class Analysis (LCA) Results 1 Background CBY Job 3 Job 2 Job 1 CBY Job 3 Job 2 Job 1 CBY Job 3 Job 2 Job 1 CBY Job 3 Job 2 Job 1 Childbearing years. Jobs 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 Age Discussion • We identified distinct patterns of time in and out of the work force among women in this population • Although women in class 1 are slightly older on average, age does not explain the differences work status or work pattern • Class 4 may represent insufficient data, not necessarily delayed entry • Prevalence of patterns may be different for women working today than for women in the cohort who entered the work force between 1933 and 1966) • Differences in health behaviors may have important implications for associations between work pattern and health Conclusions • Identification of employment patterns is an important step in understanding women’s work experiences • Next steps are to analyze associations of patterns with later life health outcomes Acknowledgements The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C. The Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Drexel University provided a faculty development grant to Dr. Michael to support this research. This project was made possible in part by financial assistance from the Ruth Landes Memorial Research Fund, a program of The Reed Foundation.