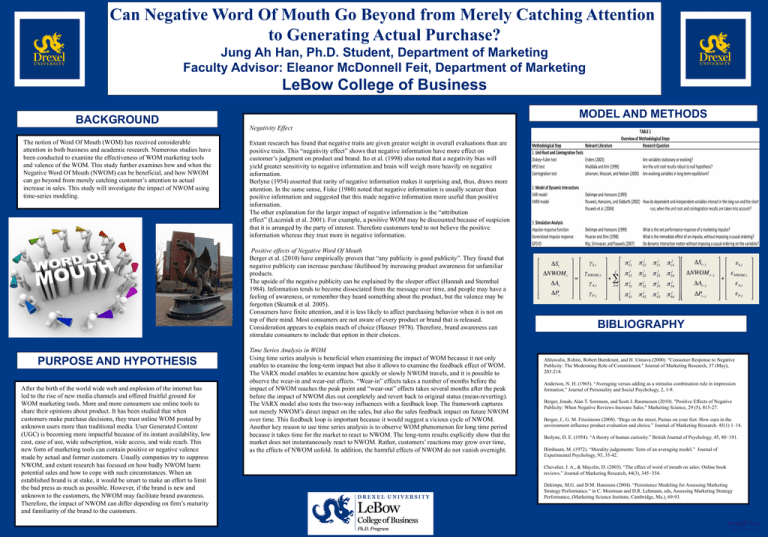

Can Negative Word Of Mouth Go Beyond from Merely Catching... to Generating Actual Purchase?

advertisement

Can Negative Word Of Mouth Go Beyond from Merely Catching Attention to Generating Actual Purchase? Jung Ah Han, Ph.D. Student, Department of Marketing Faculty Advisor: Eleanor McDonnell Feit, Department of Marketing LeBow College of Business BACKGROUND The notion of Word Of Mouth (WOM) has received considerable attention in both business and academic research. Numerous studies have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of WOM marketing tools and valence of the WOM. This study further examines how and when the Negative Word Of Mouth (NWOM) can be beneficial, and how NWOM can go beyond from merely catching customer’s attention to actual increase in sales. This study will investigate the impact of NWOM using time-series modeling. MODEL AND METHODS Negativity Effect Extant research has found that negative traits are given greater weight in overall evaluations than are positive traits. This “negativity effect” shows that negative information have more effect on customer’s judgment on product and brand. Ito et al. (1998) also noted that a negativity bias will yield greater sensitivity to negative information and brain will weigh more heavily on negative information. Berlyne (1954) asserted that rarity of negative information makes it surprising and, thus, draws more attention. In the same sense, Fiske (1980) noted that negative information is usually scarcer than positive information and suggested that this made negative information more useful than positive information. The other explanation for the larger impact of negative information is the “attribution effect” (Laczniak et al. 2001). For example, a positive WOM may be discounted because of suspicion that it is arranged by the party of interest. Therefore customers tend to not believe the positive information whereas they trust more in negative information. Positive effects of Negative Word Of Mouth Berger et al. (2010) have empirically proven that “any publicity is good publicity”. They found that negative publicity can increase purchase likelihood by increasing product awareness for unfamiliar products. The upside of the negative publicity can be explained by the sleeper effect (Hannah and Sternthal 1984). Information tends to become dissociated from the message over time, and people may have a feeling of awareness, or remember they heard something about the product, but the valence may be forgotten (Skurnik et al. 2005). Consumers have finite attention, and it is less likely to affect purchasing behavior when it is not on top of their mind. Most consumers are not aware of every product or brand that is released. Consideration appears to explain much of choice (Hauser 1978). Therefore, brand awareness can stimulate consumers to include that option in their choices. PURPOSE AND HYPOTHESIS After the birth of the world wide web and explosion of the internet has led to the rise of new media channels and offered fruitful ground for WOM marketing tools. More and more consumers use online tools to share their opinions about product. It has been studied that when customers make purchase decisions, they trust online WOM posted by unknown users more than traditional media. User Generated Content (UGC) is becoming more impactful because of its instant availability, low cost, ease of use, wide subscription, wide access, and wide reach. This new form of marketing tools can contain positive or negative valence made by actual and former customers. Usually companies try to suppress NWOM, and extant research has focused on how badly NWOM harm potential sales and how to cope with such circumstances. When an established brand is at stake, it would be smart to make an effort to limit the bad press as much as possible. However, if the brand is new and unknown to the customers, the NWOM may facilitate brand awareness. Therefore, the impact of NWOM can differ depending on firm’s maturity and familiarity of the brand to the customers. Time Series Analysis in WOM Using time series analysis is beneficial when examining the impact of WOM because it not only enables to examine the long-term impact but also it allows to examine the feedback effect of WOM. The VARX model enables to examine how quickly or slowly NWOM travels, and it is possible to observe the wear-in and wear-out effects. “Wear-in” effects takes a number of months before the impact of NWOM reaches the peak point and “wear-out” effects takes several months after the peak before the impact of NWOM dies out completely and revert back to original status (mean-reverting). The VARX model also tests the two-way influences with a feedback loop. The framework captures not merely NWOM’s direct impact on the sales, but also the sales feedback impact on future NWOM over time. This feedback loop is important because it would suggest a vicious cycle of NWOM. Another key reason to use time series analysis is to observe WOM phenomenon for long time period because it takes time for the market to react to NWOM. The long-term results explicitly show that the market does not instantaneously react to NWOM. Rather, customers’ reactions may grow over time, as the effects of NWOM unfold. In addition, the harmful effects of NWOM do not vanish overnight. BIBLIOGRAPHY Ahluwalia, Rohini, Robert Burnkrant, and H. Unnava (2000). "Consumer Response to Negative Publicity: The Moderating Role of Commitment." Journal of Marketing Research, 37 (May), 203-214. Anderson, N. H. (1965). “Averaging versus adding as a stimulus combination rule in impression formation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2, 1-9. Berger, Jonah, Alan T. Sorensen, and Scott J. Rasmussen (2010). "Positive Effects of Negative Publicity: When Negative Reviews Increase Sales." Marketing Science, 29 (5), 815-27. Berger, J., G. M. Fitzsimons (2008). “Dogs on the street, Pumas on your feet: How cues in the environment influence product evaluation and choice.” Journal of Marketing Research. 45(1) 1–14. Berlyne, D. E. (1954). “A theory of human curiosity.” British Journal of Psychology, 45, 80−191. Birnbaum, M. (1972). “Morality judgements: Tests of an averaging model.” Journal of Experimental Psychology, 93, 35-42. Chevalier, J. A., & Mayzlin, D. (2003). “The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews.” Journal of Marketing Research, 44(3), 345−354. Dekimpe, M.G. and D.M. Hanssens (2004). “Persistence Modeling for Assessing Marketing Strategy Performance.” in C. Moorman and D.R. Lehmann, eds, Assessing Marketing Strategy Performance, (Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge, Ma.), 69-93. printed by www.postersession.com