Results Background Discussion

advertisement

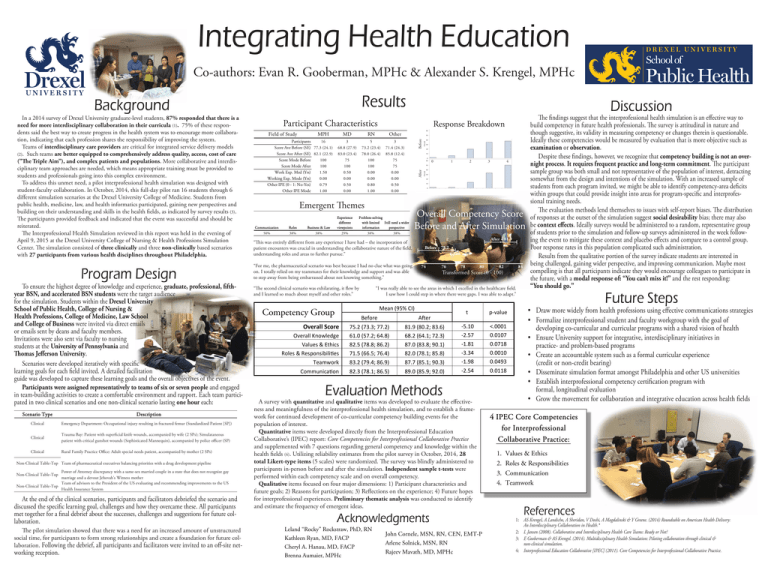

Integrating Health Education Co-authors: Evan R. Gooberman, MPHc & Alexander S. Krengel, MPHc Results Background In a 2014 survey of Drexel University graduate-level students, 87% responded that there is a need for more interdisciplinary collaboration in their curricula (1). 75% of these respondents said the best way to create progress in the health system was to encourage more collaboration, indicating that each profession shares the responsibility of improving the system. Teams of interdisciplinary care providers are critical for integrated service delivery models (2). Such teams are better equipped to comprehensively address quality, access, cost of care (”The Triple Aim”), and complex patients and populations. More collaborative and interdisciplinary team approaches are needed, which means appropriate training must be provided to students and professionals going into this complex environment. To address this unmet need, a pilot interprofessional health simulation was designed with student-faculty collaboration. In October, 2014, this full-day pilot ran 16 students through 6 different simulation scenarios at the Drexel University College of Medicine. Students from public health, medicine, law, and health informatics participated, gaining new perspectives and building on their understanding and skills in the health fields, as indicated by survey results (3). The participants provided feedback and indicated that the event was successful and should be reiterated. The Interprofessional Health Simulation reviewed in this report was held in the evening of April 9, 2015 at the Drexel University College of Nursing & Health Professions Simulation Center. The simulation consisted of three clinically and three non-clinically based scenarios with 27 participants from various health disciplines throughout Philadelphia. “This was entirely different from any experience I have had – the incorporation of patient encounters was crucial in understanding the collaborative nature of the field, understanding roles and areas to further pursue.” Program Design “For me, the pharmaceutical scenario was best because I had no clue what was going on. I totally relied on my teammates for their knowledge and support and was able to step away from being embarrassed about not knowing something.” To ensure the highest degree of knowledge and experience, graduate, professional, fifthyear BSN, and accelerated BSN students were the target audience for the simulation. Students within the Drexel University School of Public Health, College of Nursing & Health Professions, College of Medicine, Law School and College of Business were invited via direct emails or emails sent by deans and faculty members. Invitations were also sent via faculty to nursing students at the University of Pennsylvania and Thomas Jefferson University. Scenarios were developed iteratively with specific learning goals for each field invited. A detailed facilitation guide was developed to capture these learning goals and the overall objectives of the event. Participants were assigned representatively to teams of six or seven people and engaged in team-building activities to create a comfortable environment and rapport. Each team participated in two clinical scenarios and one non-clinical scenario lasting one hour each: Scenario Type Description Clinical Emergency Department: Occupational injury resulting in fractured femur (Standardized Patient [SP]) Clinical Trauma Bay: Patient with superficial knife wounds, accompanied by wife (2 SPs); Simulataneous patient with critical gunshot wounds (Sophisticated Mannequin), accompanied by police officer (SP) Clinical Rural Family Practice Office: Adult special needs patient, accompanied by mother (2 SPs) Non-Clinical Table-Top Team of pharmaceutical executives balancing priorities with a drug development pipeline Power of Attorney discrepancy with a same-sex married couple in a state that does not recognize gay marriage and a devout Jehovah's Witness mother Team of advisors to the President of the US evaluating and recommending improvements to the US Non-Clinical Table-Top Health Insurance System Non-Clinical Table-Top At the end of the clinical scenarios, participants and facilitators debriefed the scenario and discussed the specific learning goal, challenges and how they overcame these. All participants met together for a final debrief about the successes, challenges and suggestions for future collaboration. The pilot simulation showed that there was a need for an increased amount of unstructured social time, for participants to form strong relationships and create a foundation for future collaboration. Following the debrief, all participants and facilitators were invited to an off-site net- working reception. Discussion Participant Characteristics 16 Participants Score Ave Before (SE) 77.3 (24.1) Score Ave After (SE) 82.1 (22.9) 100 Score Mode Before 100 Score Mode After 1.50 Work Exp. Med (Yrs) 0.00 Working Exp. Mode (Yrs) 0.79 Other IPE (0 - 1: No-Yes) 1.00 Other IPE Mode MD RN Other 3 5 3 68.8 (27.9) 73.2 (23.4) 71.4 (24.3) 83.0 (23.4) 78.0 (26.4) 85.8 (12.4) 75 100 75 100 100 75 0.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.50 0.80 0.50 0.00 1.00 0.00 Before MPH 0 Emergent Themes Communication Roles Business & Law Experience different viewpoints 50% 38% 38% 29% Problem-solving with limited Still need a wider information perspective 38% 1 3 4 38% Overall Competency Score Before and After Simulation After = 81.9 Before = 75.2 74 76 78 80 82 84 Transformed Score (0 - 100) “I was really able to see the areas in which I excelled in the healthcare field. I saw how I could step in where there were gaps. I was able to adapt.” “The second clinical scenario was exhilarating, it flew by and I learned so much about myself and other roles.” Mean (95% CI) Competency Group 2 After Field of Study Response Breakdown t p-value Before After Overall Knowledge Values & Ethics Roles & Responsibilities Teamwork 75.2 (73.3; 77.2) 61.0 (57.2; 64.8) 82.5 (78.8; 86.2) 71.5 (66.5; 76.4) 83.2 (79.4; 86.9) 81.9 (80.2; 83.6) 68.2 (64.1; 72.3) 87.0 (83.8; 90.1) 82.0 (78.1; 85.8) 87.7 (85.1; 90.3) -5.10 -2.57 -1.81 -3.34 -1.98 <.0001 0.0107 0.0718 0.0010 0.0493 Communication 82.3 (78.1; 86.5) 89.0 (85.9; 92.0) -2.54 0.0118 Overall Score Evaluation Methods A survey with quantitative and qualitative items was developed to evaluate the effectiveness and meaningfulness of the interprofessional health simulation, and to establish a framework for continued development of co-curricular competency building events for the population of interest. Quantitative items were developed directly from the Interprofessional Education Collaborative’s (IPEC) report: Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice and supplemented with 7 questions regarding general competency and knowledge within the health fields (4). Utilizing reliability estimates from the pilot survey in October, 2014, 28 total Likert-type items (5 scales) were randomized. The survey was blindly administered to participants in-person before and after the simulation. Independent sample t-tests were performed within each competency scale and on overall competency. Qualitative items focused on four major dimensions: 1) Participant characteristics and future goals; 2) Reasons for participation; 3) Reflections on the experience; 4) Future hopes for interprofessional experiences. Preliminary thematic analysis was conducted to identify and estimate the frequency of emergent ideas. Acknowledgments Leland “Rocky” Rockstraw, PhD, RN Kathleen Ryan, MD, FACP Cheryl A. Hanau, MD, FACP Brenna Aumaier, MPHc John Cornele, MSN, RN, CEN, EMT-P Arlene Solnick, MSN, RN Rajeev Mavath, MD, MPHc The findings suggest that the interprofessional health simulation is an effective way to build competency in future health professionals. The survey is attitudinal in nature and though suggestive, its validity in measuring competency or changes therein is questionable. Ideally these competencies would be measured by evaluation that is more objective such as examination or observation. Despite these findings, however, we recognize that competency building is not an overnight process. It requires frequent practice and long-term commitment. The participant sample group was both small and not representative of the population of interest, detracting somewhat from the design and intentions of the simulation. With an increased sample of students from each program invited, we might be able to identify competency-area deficits within groups that could provide insight into areas for program-specific and interprofessional training needs. The evaluation methods lend themselves to issues with self-report biases. The distribution of responses at the outset of the simulation suggest social desirability bias; there may also be context effects. Ideally surveys would be administered to a random, representative group of students prior to the simulation and follow-up surveys administered in the week following the event to mitigate these context and placebo effects and compare to a control group. Poor response rates in this population complicated such administration. Results from the qualitative portion of the survey indicate students are interested in being challenged, gaining wider perspective, and improving communication. Maybe most compelling is that all participants indicate they would encourage colleagues to participate in the future, with a modal response of: “You can’t miss it!” and the rest responding: “You should go.” Future Steps • Draw more widely from health professions using effective communications strategies • Formalize interprofessional student and faculty workgroup with the goal of developing co-curricular and curricular programs with a shared vision of health • Ensure University support for integrative, interdisciplinary initiatives in practice- and problem-based programs • Create an accountable system such as a formal curricular experience (credit or non-credit bearing) • Disseminate simulation format amongst Philadelphia and other US universities • Establish interprofessional competency certification program with formal, longitudinal evaluation • Grow the movement for collaboration and integrative education across health fields 4 IPEC Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 1. 2. 3. 4. Values & Ethics Roles & Responsibilities Communication Teamwork References 1: AS Krengel, A Landicho, A Sheridan, V Doshi, A Magdalinski & Y Greene. (2014) Roundtable on American Health Delivery: An Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Health.* 2: L Jansen (2008). Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Health Care Teams: Ready or Not? 3: E Gooberman & AS Krengel. (2014). Multidisciplinary Health Simulation: Piloting collaboration through clinical & non-clinical simulation. 4: Interprofessional Education Collaborative [IPEC] (2011). Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice.