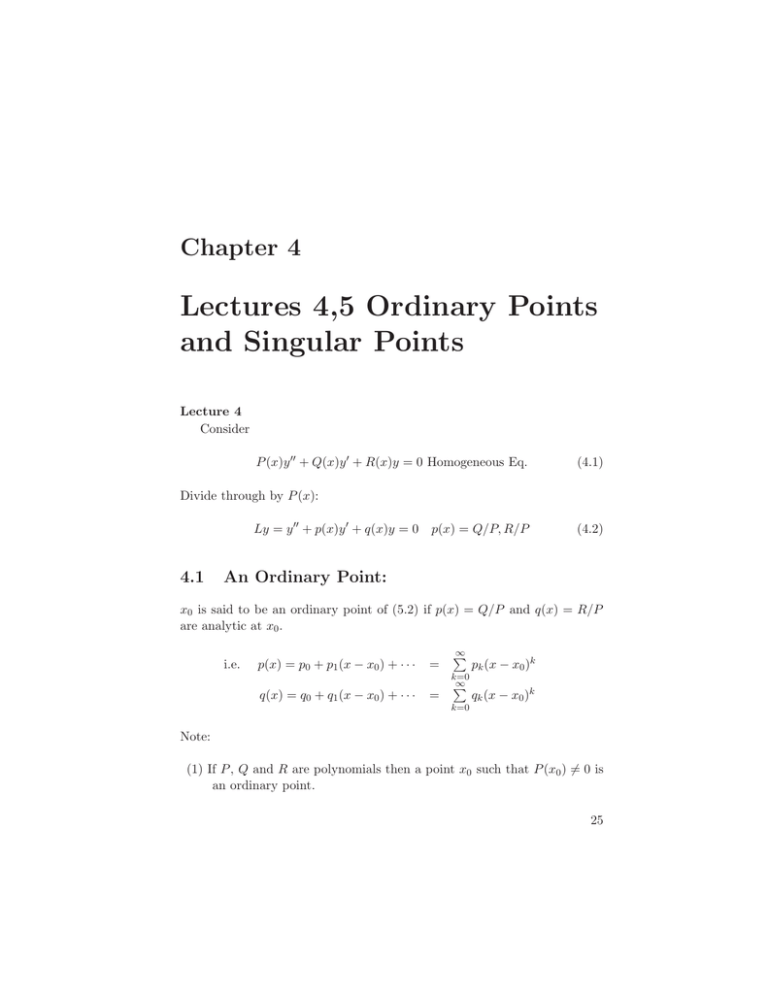

Lectures 4,5 Ordinary Points and Singular Points Chapter 4 4.1

advertisement

Chapter 4

Lectures 4,5 Ordinary Points

and Singular Points

Lecture 4

Consider

P (x)y + Q(x)y + R(x)y = 0 Homogeneous Eq.

(4.1)

Divide through by P (x):

Ly = y + p(x)y + q(x)y = 0 p(x) = Q/P, R/P

4.1

(4.2)

An Ordinary Point:

x0 is said to be an ordinary point of (5.2) if p(x) = Q/P and q(x) = R/P

are analytic at x0 .

i.e.

p(x) = p0 + p1 (x − x0 ) + · · ·

=

q(x) = q0 + q1 (x − x0 ) + · · ·

=

∞

k=0

∞

k=0

pk (x − x0 )k

qk (x − x0 )k

Note:

(1) If P , Q and R are polynomials then a point x0 such that P (x0 ) = 0 is

an ordinary point.

25

Lectures 4,5 Ordinary Points and Singular Points

(2) If x0 = 0 is an ordinary point then we assume

y =

0 = Ly =

∞

n=0

∞

n

cn x

, yn

∞

=

n−1

cn nx

n=1

cn n(n − 1)xn−2 +

n=2

+

∞

n

qn x

n=0

, yn

cn n(n − 1)xn−2

n=2

∞

∞

pn xn

n=0

∞

=

∞

ncn xn−1

(4.3)

n=1

n

cn x

n=0

∞

(m + 2)(m + 1)cm+2 + p0 (m + 1)cm+1 + · · · + pm c1

m=0

+ (q0 cm + · · · + qm c0 )} xm = 0

(4.4)

yields a non-degenerate recursion for the cm .

At an ordinary point x0 we can obtain two linearly independent solutions by power series expansion.

About x0 :

y(x) =

∞

cn (x − x0 )n .

(4.5)

n=0

(3) The radius of convergence of (4.5) is at least as large as the radius of

convergence of each of the series p(x) = Q/P q(x) = R/P .

i.e. up to the closest singularity to x0 .

4.2

A Singular Point:

If p(x) or q(x) are not analytic at x0 , then x0 is said to be a singular point

of (4.2). For example if P , Q and R are polynomials and P (x0 ) = 0 and

Q(x0 ) = 0 or R(x0 ) = 0 then x0 is a singular point.

EG:

(4.6)

(x − 1)y + y = 0

x = 0 is an ordinary point.

x = 1 is a singular point.

Expand around the ordinary point

y(x) =

∞

n=0

26

cn xn ,

y =

∞

n=1

ncn xn−1 ,

y =

∞

n=2

cn n(n − 1)xn−2

(4.7)

4.2. A SINGULAR POINT:

(x − 1)

−

∞

∞

cn n(n − 1)xn−2 +

n=2

cn n(n − 1)xn−2 +

n=2

∞

∞

ncn xn−1 = 0

n=1

cn {n(n − 1) + n} xn−1 + c1 = 0

(4.8)

n=2

m−1=n−2⇒m=n−1 n=2⇒m=1 n=m+1

∞

−cm+1 (m + 1)m + cm m2 xm−1 = 0

−c2 · 2 · 1 + c1 +

m=2

c0 Arbitrary:

c1

m

cm m ≥ 2 c2 =

m+1

2

2

c1

3

c1

c1

c2 =

c4 = c3 =

. . . cn =

c3 =

3

3

4

4

n

∞

n

x

.

Therefore y(x) = c0 + c1

n

cm+1 =

(4.9)

n=1

Recall

1

= 1 + x + x2 + · · ·

1−x

y(x) = A + B ln |x − 1|

x2 x3

1

dx = − ln |1 − x| = x +

+

+ ···

1−x

2

3

(4.10)

But (4.6) is also an Euler Equation:

y = (x − 1)r ⇒ r(r − 1) + r = r2 = 0 r = 0, 0.

y(x) = A + B ln(x − 1)

(4.11)

27