A Brief History of the M.Ed. TEFSL Program

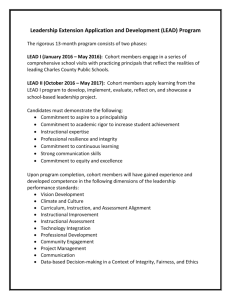

advertisement