ANALYSIS OF FUEL BEHAVIOR IN THE SPARK IGNITION ENGINE START-UP PROCESS

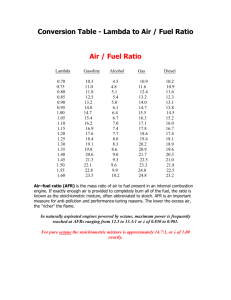

advertisement