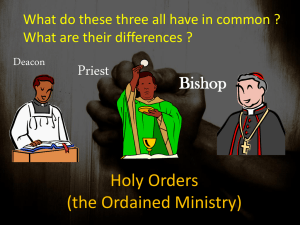

the vocations of religious

advertisement