European intertidal marshes: a review of their REVIEW *, H. Hampel

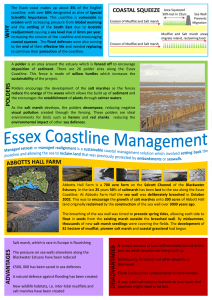

advertisement