On the Impact of Microcredit: Evidence from a Randomized

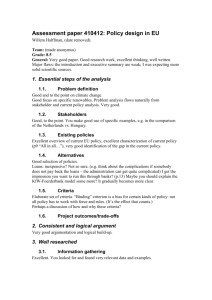

advertisement