COURSE OBJECTIVES CHAPTER 9 9. SHIP MANEUVERABILITY

advertisement

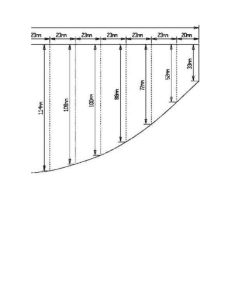

COURSE OBJECTIVES CHAPTER 9 9. SHIP MANEUVERABILITY 1. Be qualitatively familiar with the 3 broad requirements for ship maneuverability, namely. a. Controls fixed straightline stability b. Response c. Slow speed maneuverability 2. Qualitatively describe what each requirement is dependant upon. 3. Briefly describe the various common types of rudder. 4. Understand the various dimensions of the spade rudder, in particular 5. a. Chord b. Span c. Rudder stock d. Root e. Tip Qualitatively describe the meaning of: a. Unbalanced Rudder b. Balanced Rudder c. Semi-balanced rudder 6. Qualitatively describe the sequence of events that causes a ship to turn. 7. Qualitatively describe a rudder stall and understand what it means. (i) 8. Qualitatively describe the arrangement and devices that can be used to provide a ship with maneuverability at slow speeds. Namely: a. Rudder position b. Twin propellers c. Lateral thrusters d. Rotational thrusters (ii) 9.1 Introduction Ship maneuverability is a very complex and involved subject involving the study of equations of motion involving all 6 ship movements. Analysis of these motion equations allows predictions of ship maneuverability to be made. However, many assumptions are made, so model testing is required to verify analytical results. Once built, a ship’s maneuvering characteristics are quantified during its Sea Trials. To limit the level of complexity covered in this chapter, the analytical study of the equations of motion will be ignored. However, maneuverability requirements a ship designer strives to meet will be discussed along with the devices and their arrangements that can provide them. After completing this chapter you will have an understanding of how a ship’s rudder makes a ship turn and an appreciation of other devices that improve a ship’s slow speed maneuverability. 9-1 9.2 Maneuverability Requirements When given the task of designing a ship, the Naval Architect is given a number of design requirements to meet. These include the obvious dimensions such as LPP, Beam and Draft, but also other requirements such as top speed, endurance etc. Some of the more complicated requirements involve maneuverability. These can be split into 3 broad categories. 9.2.1 Directional Stability In many operational circumstances, it is more important for a ship to be able to proceed in a straight line than turn. That is, with the rudder set at midships, and in the absence of external forces, the ship will travel in a straight line. This is termed controls fixed straight line stability. Our experience indicates that this scenario is rarely the case, and anything but a sea directly on the bow will create a yawing moment that has to be compensated for by movement of the ship’s rudder. However, in principle, ships should be designed to achieve controls fixed straight line stability. An illustration of this stability is at Figure 9.1. Figure 9.1 – Hull Forms with Different Levels of Directional Stability Despite this requirement, many hull forms do not have this level of directional stability. In particular, ships which are relatively short and wide such as tugs or harbor utility vessels and in certain circumstances, small combatants tend to have poor controls fixed straightline stability. This can be overcome by increasing the amount of deadwood of the hull (fin-like vertical surface) at the stern. This is directly analogous to the flights on an arrow or dart. Without flights, the arrow will tend to yaw in flight. With flights, the arrow maintains a straightline. Hence increasing the amount of deadwood will increase the directional stability properties of a hull. For a ship, the problem is worsened because the ship is pushed rather than pulled along. Try pushing the end of your pencil and maintain its motion in a straight line! Controls fixed straightline stability is quantified during sea trials by the spiral maneuver where rate of turn is compared with rudder direction. 9-2 9.2.2 Response In opposition to the requirement for controls fixed straightline stability, it is also required for the ship to turn in a satisfactory manner when a rudder order is given. In particular: • • The ship must respond to its rudder and change heading in a specified minimum time. There should be minimum overshoot of heading after a rudder order is given. In practice, both these response quantities are dependant upon the magnitude of the rudder’s dimensions, the rudder angle and ship speed. 9.2.2.1 Rudder Dimensions As we will see in the next section, rudder dimensions are limited by the geometry of the ship’s stern. However, it is not surprising that the larger the dimensions of the rudder, the more maneuverable the ship. Increasing the rudder dimensions decreases the response time and overshoot experienced by the hull. The level of response required by a ship is driven by its operational role. For example, the ratio of rudder area to the product of length and draft ranges from 0.017 for a cargo ship to 0.025 for destroyers. Rudder Area Ratio = Rudder Area L pp T 9.2.2.2 Rudder Angle Clearly, the response characteristics of a ship will depend upon the rudder angle ordered for a particular maneuver. It is common procedure for the levels of response to be specified with the ship using standard rudder. This is 20 degrees of wheel for the USN. 9.2.2.3 Ship Speed Ship speed will also influence the level of maneuverability being experienced by the ship. In practice, for the majority of hull forms, greater ship speed will reduce response time but increase overshoot. This is because greater ship speed increases the rudder force being generated by a given rudder angle. For this reason, during sea trials, ship response and overshoot is quantified at several ship speeds. Ship response is usually assessed by the zig-zag maneuver. 9-3 9.2.3 Slow Speed Maneuverability It is usually the case that it is most important for ships to be maneuverable when traveling at slow speeds. This is because evolutions such as canal transits and port entrances are performed at slow speeds for safety reasons. Unfortunately, this is when the ship’s rudder is least effective. Levels of slow speed maneuverability are specified in terms of turning circle and other quantifiable parameters at speeds below 5 knots. Devices that can improve slow speed maneuverability will be discussed later. 9.2.4 Maneuverability Trade-Off Unfortunately, the need for good directional stability (in particular controls fixed straightline stability) and minimum ship response oppose each other. For example, for a fixed rudder area, increasing the length of a ship will make it more directionally stable but less responsive to its rudder. As discussed, a similar effect is created by increasing the amount of vertical flat surface at the stern (deadwood). However, increasing rudder area will always improve the response characteristics of a hull form and usually improve its directional stability as well. Unfortunately, rudder dimensions are limited by stern geometry. Also larger rudders will increase drag and so reduce ship speed for a given DHP from the propeller. 9-4 9.3 The Rudder 9.3.1 Rudder Types Clearly, the rudder is the most important control surface on the hull. There are a multiplicity of different types. Figure 9.2 reproduced from the SNAME publication “Principles of Naval Architecture” shows some of them. Figure 9.2 – Different Rudder Types The magnitude of all the rudder types dimensions are limited by the stern. • Chord The chord is limited by the position of the propeller (propeller/rudder clearance is specified by the American Bureau of Shipping for US ships) and the edge of the stern. It is fairly obvious that a rudder protruding beyond the stern is inadvisable. • Span The span is limited by the hull and the need for the rudder to remain above the ship baseline. This is a “grounding” consideration. 9-5 9.3.2 The Spade Rudder The most common type of rudder found on military vessels is the spade rudder. Figure 9.3 from “Introduction to Naval Architecture” by Gilmer and Johnson shows the geometry of a typical semi-balanced spade rudder. Figure 9.3 – A Semi-balanced Spade Rudder 9.3.2.1 Rudder Balance Whether a rudder is balanced or not is dependant upon the relationship of the center of pressure of the rudder and the position of the rudder stock. • When they are vertically aligned, the rudder is said to be “fully balanced”. This arrangement greatly reduces the torque required by the tiller mechanism to turn the rudder. • When the rudder stock is at the leading edge, the rudder is “unbalanced” as in Figure 9.2(a). This is a common arrangement in merchant ships where rudder forces are not excessive. • The spade rudder in Figure 9.3 is semi-balanced. This is a sensible arrangement as it limits the amount of torque required by the tiller mechanism yet should ensure the rudder returns to midships after the occurrence of a tiller mechanism failure. 9-6 9.3.3 Rudder Performance It is a common misconception that the rudder turns a ship. In fact, the rudder is analogous to the flaps on an aircraft wing. The rudder causes the ship to orientate itself at an angle of attack to its forward motion. It is the hydrodynamics of the flow past the ship that causes it to turn. Figure 9.4 shows the stages of a ship turn. Figure 9.4 – The Stages of a Ship’s Turn The ship will continue to turn until the rudder angle is removed. 9.3.3.1 Rudder Stall You will probably have noticed that a typical ship’s rudder is limited to a range of angles from about ± 35 degrees. This is because at greater angles than these the rudder is likely to stall. Figure 9.5 from Gilmer & Johnson shows the development of stall as rudder angle increases. At small angles, rudder lift is created due to the difference in flow rate across the port and starboard sides of the rudder. However, as rudder angle increases, the amount of flow separation increases until a full stall occurs at 45 degrees. 9-7 Figure 9.5 – Rudder Flow Patterns at Increasing Rudder Angle The amount of lift achieved by the rudder reduces significantly after a stall and is matched by a rapid increase in drag. Consequently, rudder angle is limited to values less than the stall angle. Figure 9.6 shows how rudder lift alters with rudder angle. Figure 9.6 – How Lift Alters with Rudder Angle 9-8 9.4 Slow Speed Maneuverability As mentioned previously, it is at slow speeds when ships need to be the most maneuverable. Unfortunately, at slow speeds the rudder is limited in its effectiveness due to the lack of flow across its surfaces. However, there are several things that can be done to improve the situation. 9.4.1 Rudder Position To improve the low flow rate experienced by the rudder at slow speeds, the rudder is often positioned directly behind the propeller. In this position, the thrust from the propeller acts directly upon the control surface. A skilled helmsman can then combine the throttle control and rudder angle to vector thrust laterally and so create a larger turning moment. 9.4.2 Twin Propellers The presence of 2 propellers working in unison can significantly improve slow speed maneuverability. By putting one prop in reverse and the other forward, very large turning moments can be created with hardly any forward motion. 9.4.3 Lateral Thrusters Lateral thrusters (or bow thrusters as they are usually positioned at the bow) consist of a tube running athwart ships inside of which is a propeller. They are usually electrically driven. With a simple control from the bridge, the helmsman can create a significant turning moment in either direction. Figure 9.7 shows a photograph of 2 lateral thrusters positioned in the bulbous bow of a ship. The photo is reproduced from “Introduction to Naval Architecture” by Gilmer and Johnson. Figure 9.7 – Lateral Thrusters in the Bow of a Ship 9-9 9.4.4 Rotational Thrusters These provide the ultimate configuration for slow speed maneuverability. Rotational thrusters’ appearance and operation resembles an outboard motor. They consist of pods that can be lowered from within the ship hull. Once deployed, the thruster can be rotated through 360 degrees allowing thrust to be directed at any angle. Figure 9.8 shows a typical “ro-thruster” design produced by Kværner Masa-Azipod of Finland. Figure 9.8 – Typical Rotational Thruster Design Some highly specialized ships use “ro-thrusters” as their only means of propulsion. 2 or 3 “rothrusters’ coupled with a complicated G.P.S. centered control system can keep a ship in a geostationary position over the sea bed and at the same heading in quite considerable tide and wave conditions. These ships are often associated with diver, salvage or seabed drilling operations. Figure 9.9 on the following page shows a typical auxiliary propulsion unit used on ships and submarines. It can be used for both emergency propulsion and maneuverability. ! In practice, the amount of slow speed maneuverability exhibited by a ship is largely dependant upon the amount of money the designer is willing to spend on lateral or rotational thrusters in the ship design. This economic question is highly involved and includes estimates of ship docking rates, the costs of hiring tugs etc. 9 - 10 Figure 9.9 – Auxiliary Propulsion Unit 9 - 11 CHAPTER 9 HOMEWORK 1. A small 30 ft pleasure craft you own is very difficult to steer. In particular the smallest amount of wind or sea makes it almost impossible to keep on course. While the boat is out of the water for the winter, what modification could you make to the hull to improve its maneuvering characteristics? 2. A ship with LPP = 500 ft, B = 46 ft, and T = 20 ft is being designed for good maneuverability (i.e. short response times and minimum overshoot). a. Estimate a suitable rudder area for this ship. b. What would constrain the dimensions of this rudder from being larger. 3. Describe a design improvement that would alter a simple rudder such as that at Figure 9.2a into a semi-balanced rudder. Why is this a better design. 4. Describe using a sketch the stages of a ship’s turn. Why does a ship slow down when it turns? 5. Describe 3 ways in which a ship’s slow speed maneuverability can be improved. 9 - 12