Document 11093666

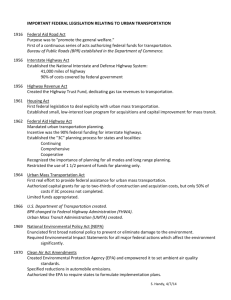

advertisement