9 L E A R N I N G T O... Peter Dobkin Hall

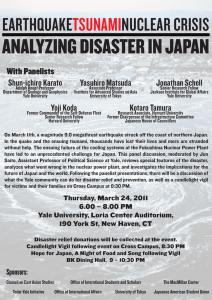

advertisement