SENATE Proof Committee Hansard LEGAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL LEGISLATION COMMITTEE MONDAY, 26 JULY 2004

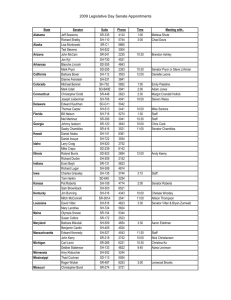

advertisement