Document 11090197

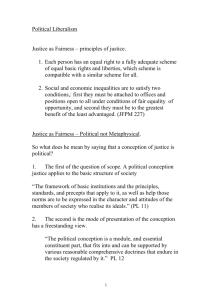

advertisement