Sage Advice: CIHE 1 International Advisory Councils at

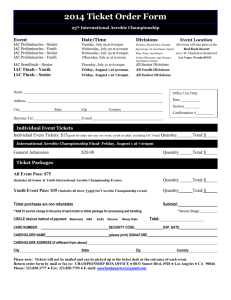

advertisement