A Watershed Management Approach to Land Stewardship

advertisement

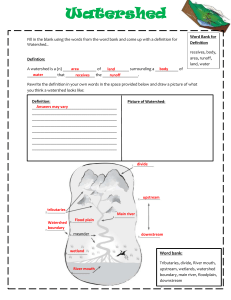

A WatershedManagement Approachto LandStewardship Peter F. Ffolliott, School of RenewableNaturalResources, University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85721; Malchus B. Baker, Jr., Rocky MountainResearchStation,USDA Forest Service, Flagstaff AZ 86001; Aregai Tecle, School of Forestry,NorthernArizonaUniversity,Flagstaff AZ 86011; and Daniel G.Neary, Rocky MountainResearchStation,USDA Forest Service, FlagstaffAZ 86001 Abstract Becausewatershedmanagementmeansdifferentthingsto differentpeople- even experiencedwatershedmanagers have differingperspectives- it is importantto develop andpresenta perspectiveof watershedmanagementthatfosters understandingand appreciationof its contributionsto land stewardship.Watershedmanagementorganizesand guides the use of land,water,andothernaturalresourcesto providethe goods andservices demandedby society, while ensuring the sustainabilityof the soil and waterresources.A watershedmanagementapproachto land stewardshipincorporates soil andwaterconservationandland-useplanningintoa holistic andlogical framework.This is necessarybecausepeople are affectedby the interactionbetweenwaterand otherresources,andbecausepeople influencethe natureand severity of these interactionswhen they use resources.Adoption of a watershedmanagementapproachto land stewardshipis accomplishedthroughthe combinedeffortsof technicallytrainedplannersand managers,decisionmakers,locally led advocacygroups,and otherconcernedstakeholders. Introduction Ask a land manager,stakeholder,and decisionmakerwhatwatershedmanagementmeans,andyou will likely hearthreedifferentperspectives.Because of the lack of a comprehensive, unified view of watershedmanagement,it is importantto develop andpresenta perspectivethat fostersunderstanding and an appreciationof its contributionsto land stewardship.Theperspectivepresentedin this paper is baseduponthe following definitionsandconcepts (Brooksetal. 1992, 1994, 1997;NationalResearch Council 1999; Neary 2000). A watershedis: • A topographicallydelineatedarea drainedby a streamsystem; • The total land area above some point on a streamor riverthat drainspast thatpoint; • A hydrologic-responseunit, a physical-biological unit, and a socioeconomic political unit for managementplanning;and • A smallerupstreamcatchmentthat is part of a river basin (Brooks et al. 1992, 1994, 1997; NationalResearchCouncil 1999; Neary 2000). A river basin is a watershedon a largerscale. For example,the Ohio River Basin, the Mississippi River Basin, and the ColoradoRiver Basin include all of the watersheds that drain into the Ohio, Mississippi, and ColoradoRivers, and their tributaries,which all eventuallyflow into the ocean. Somepeople erroneouslybelieve thatwatershed managementonly concernsthebiophysicalinterrelationships; however, it is much more. Watershed management'. Organizes and guides the use of land, water, and other naturalresources on a watershedto provide the goods and services demandedby society, while ensuring the sustainability of the soil and water resources; • Involves the interrelationships among soil, water, and land use, and the links between uplandand downstreamareas; • Considers the connection between stream channel responses and the impacts caused by natural or human-relatedevents on the surroundingwatershed;an • Involves socioeconomic and human-institutional interrelationshipsalong with biophysical interrelationships. Keeping the above points in mind helps to guide watershed managementpractices and identify the institutional mechanisms needed to implement a watershedmanagementapproachto land stewardship. Watershedmanagementpractices are changes in land use, vegetative cover, and other nonstructural and structuralactions conducted on a watershed to achieve ecosystem-based, multiple-use management objectives. Objectives of watershed managementpractices include: • Rehabilitationof degradedlands; • Protectionof soil and waterresourceson lands managed to produce food, fiber, forage, and otherproducts; • Improvement of amenities, such as a landscape's aesthetic value; • Enhancementof waterquantityandquality;and • Any combinationof these objectives. Ffolliott, P. FMM.B. Baker, Jr., A. Tecle, and D. G. Neary. 2003. A Watershed Management Approach to Land Stewardship. Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Sc/ea/ce35(1):1-4. ©2003 Peter F. Ffolliott, Malchus B. Baker, Jr., Aregai Tecle, and Daniel G. Neary. 2 A Watershed ManagementApproach to Land Stewardship + Ffolloitt, Baker, Tecle, and Neary A watershed management approach to land stewardshipincorporatessoil andwaterconservation and land-use planning into a holistic and logical framework.This is necessary because people are positively andnegatively affectedby the interaction between water and other resources, and because people influence the nature and severity of these interactionswhen they use resources. The effects of these interactions follow watershed,not political, boundaries- water flows downhill despite political boundaries. Activity on the uplands of one political unit affects other politicalunits thatoccupy a downstreamposition in a watershed or river basin. Because these interactions disregardpolitical boundaries, considering naturalresource use on a broad, societal scale is important.A watershed management approachto land stewardshipconsiders downstreamor off-site effects by establishingwatershedboundaries.When off-site effects exist, ecologically sound management becomes good economics if the costs and benefitsof the managementactivities aredistributed amongthe involved communities,political entities, and individuals. Whya WatershedManagement Approachto LandStewardship? Naturalecosystems aremanagedto improvethe welfare of people within the confines of the practices of a watershedmanagementapproachto land stewardship. Watershed management activities maximize the sustainableuse of naturalresources and the equitable distributionof the benefits and costs, while minimizing social disruptionand adverse environmentalimpacts(Gregersenet al. 1987; Brooks et al. 1992, 1994, 1997; Neary 2000). As a spatialunit of planning and management,a watershed highlights the physical aspects of the landscape. If the physical aspects of the landscape are not recognized, natural resource loss, ecological dysfunction,environmentaldegradation,and difficulty implementing watershed management interventionsmight result.A watershedunit containsthe links and issues that must be considered during futurelandstewardship(NationalResearchCouncil 1999). Even if the land stewardshipeffort focuses on waterresources,forestryactivities,livestockproduction, or agriculture,the following points illustrate the importance of a watershed management approachto land stewardship. • A watershedis a functionalarea of a landscape that includes the key interrelationshipsand interdependencies for management of land, water,and othernaturalresources. • • • • • • A watershedmanagementapproachevaluates the biophysical relationshipbetween upstream and downstream activities, which enables planners, managers, and decisionmakers to identifyandevaluateeffective landstewardship methods. The complexities of biophysical, economic, social, and institutionalfactorsthat allow developmentof sustainablemanagement programsare considered. Using the watershedas a unitof managementis economicalbecausea watershedinternalizesthe off-site effects involved with land stewardship. A watershed unit permits both upstreamand downstream assessment of environmental impacts, including the effects of land-use activities on large and small ecosystems. Consequently, the effects of upland disturbances, which result in a chain of downstream consequences, are easily examined and evaluatedwithin a watershedcontext. A watershedmanagementapproachconsiders humaninteractionswith the environment. A watershedmanagementapproachefficiently integratesother naturalresource conservation anddevelopmentprograms,e.g., soil andwater conservation, forestry, farming systems, and ruraland communitydevelopment. A watershedmanagementapproachconsiders naturalecosystems and social systems, in contrastto earlierapproachesthatfocusedeitheron natural ecosystems and ignored the social systemsor on social systemsandconsideredthe naturalecosystem as a constraint(Gregersenet al. 1987, Quinnet al. 1995, Brooks et al. 1997, Neary 2000). Adoptionof a WatershedManagementApproachto LandStewardship Some barriersto the adoptionof a watershed management approach to land stewardship are actual, while others are perceived (Brooks et al. 1992; Quinnet al. 1995; Ffolliottet al. 2000, 2002). The combinedeffortsof technicallytrainedplanners andmanagers,decisionmakers,locally led advocacy groups,and otherconcernedstakeholdersare overcomingbothreal andimaginedobstaclesto a watershed managementapproachto land stewardship. ExistingBarriers The concepts underlyinga watershedmanagementapproachto land stewardshippartiallyexplain why this approach has not been more widely adopted(Gregersenet al. 1987, Brooks et al. 1992, Quinn et al. 1995, Ffolliott et al. 2002). Watershed managementpracticesthatare implementedby one A Watershed ManagementApproach to LandStewardship + Ffolloitt, Baker, Tecle, and Neary political unit often affect those living outside and especiallydownstreamof the implementingpolitical unit. Consequently,there is often little incentive to adopta watershedmanagementapproachthatcould createa conflict situation. The initiating political unit has had little incentive to implement a watershed management approachbecause those living outsidethatpolitical unit often experience the impact of the watershed managementpractices. Questionscommonly asked by upstreamland users illustratethe complexity of the situation:Why should we implementwatershed managementpracticesthatprimarilybenefit downstreamusers?Why do decisionmakersexpect us to implementa watershedmanagementapproachthat considerspeople downstreamif we arenot compensatedfor the costs? To gain the supportnecessaryto adopt a watershed management approachto land stewardship,the inequitiesof who pays for andwho benefits from a watershed management practice must be resolved. Other barriers to a watershed management approachto land stewardshipinclude: • A lack of awarenessor understandingaboutthe concepts and practices of watershed management by the planners,managers,and decisionmakerswho areresponsibleforlandstewardship and by the public; • A need for trained watershed managers to explain the natureof a watershedmanagement approachto administrators,decisionmakers,and the public adequately; • Skepticismandlimitedquantitativeinformation about the downstream benefits of watershed managementbecause the process used to evaluate andmonitorthe effectivenessof watershed managementis inadequate; • Limited understanding about the difference between the human-causedeffects of land-use practicesandthose causedby naturalprocesses; • Unrealistic expectations about the results of watershedmanagementinterventions;and • A lack of technicalexpertiseabouthow to plan, implement,andmonitorwatershedmanagement programs. Technical experts are attemptingto illustrate how watershedmanagementcan help land stewardship efforts focus on securing the flows of natural andeconomicresources.However,this effortshould includeevaluatingthe investment,employment,and incomeopportunitiesandmaintainingenvironmental quality,within a sustainableframework. Erosion, sedimentation, and flooding occur naturally,regardlessof humanactivities. However, humanactivities on watershedlands affect the frequencyandseverityof theseprocesses.Forexample, 3 excessive livestock grazing might influence the occurrenceof flooding and sedimentdeposition. Watershedmanagementimplementedto reduce the accumulation of sediment in downstream reservoirsappearsunsuccessful if naturalerosionsedimentationprocesses arenot noted. Specifically, the amount of the watershed area affected by the practices, the proximity to a reservoir, existing levels of sedimentin the streamchannels,andother current land uses should be considered. Early involvement of professionals who are experienced in the disciplines embeddedin watershedmanagement, such as hydrology, geology and soil science, forestryandrangelandmanagement,andagronomy, helps to meet the goals of a watershedmanagement programsuccessfully. Overcomingthe Barriers The barriersto the adoption of a watershed management approach to land stewardship are slowly being eliminated.Most of the planners,managers,anddecisionmakerswho areconcernedabout futureland stewardshipissues recognizethe importance of environmentallyhealthy,sustainableuse of naturalresources(Gregersenet al. 1987; Brooks et al. 1992, 1994; Quinn et al. 1995; Ffolliott et al. 2002). However,ignoringnaturallyoccurringboundaries and interrelationshipswill lead to serious consequences. A "cure all" watershed managementformula that would effectively replace current land-use practices does not exist. Further,development of naturaland economic resourceswithin a watershed managementframeworkdoes not mean that associatedprojects,programs,andactivitiesshouldbe the sole responsibilityof watershedmanagers.Instead, watershedmanagersshouldbe integralcomponents in development programs that focus on water resources,forestry,agriculture,andrelatedlandand resource uses (Ffolliott et al. 2000, 2002). To be effective, land-use administrators,water resource managers,foresters,agriculturalists,in conjunction with watershedmanagers,must practicewatershed managementactivities. Overcoming the barriers to a watershed managementapproachto land stewardshiprequires responsible government agencies and locally led partnerships, councils, corporations, and other institutionsto: • Increase stakeholder awareness about the importanceof sustainablelanduse andthe relationships that are the basis of watershedmanagement,includingthe biophysicalrealitiesand economic, social, andculturalfactorsthataffect land use on watershedlands; 4 • • • • • A Watershed ManagementApproach to Land Stewardship + Ffolloitt, Baker, Tecle, and Neary Identifyupstreamanddownstreamstakeholders in any watershed-useissue, and determinetheir perceptionsand motivations; Clarifyagency or institutionaljurisdictionover watershedmanagementactivities, and improve coordination. This is especially significant because often multiple entities are responsible fornaturalresourcemanagementon a watershed scale; Facilitate the local management of upland naturalresourcesby residentson watershedsthat areprivately owned or controlled; Fairly distributethe benefits and costs associated with upland natural resource use and watershed managementpractices between the upland and downstream land users and other stakeholders;and Assess the short- and long-term impacts of watershedmanagementpractices to encourage andimprove continuedapplication.A feedback mechanismfor this assessment should identify whether production activities and the soil and waterresourceson which these activitiesdepend are sustainableunderthe currentpolicies. Summary The perception of watershedmanagementhas changed throughoutthe twentieth century (Neary 2000). Watershedmanagement,at the beginning of the century,was concerned aboutthe development andmaintenanceof water supplies.However,today the scope and applicationof watershedmanagement is comprehensiveand dependsuponall the involved partiesunderstandingthe componentsof watersheds, and their interactions,not just the manipulationof the physicalprocesses (Reimold 1998). The goals of watershedmanagementare to assess the effects of currentand anticipatedfutureland uses on soil and water resources, determinethe potential ecological and social impacts of these land uses, and provide comprehensive solutions to watershed problems. Achieving these goals depends upon the expertise providedby watershedmanagementprofessionals. LiteratureCited Brooks, K. N., P. F. Ffolliott, H. M. Gregersen, and L. F. DeBano. 1997. Hydrology and the management of watersheds. 2ndedition. Iowa StateUniversity Press, Ames. Brooks, K. N., P.F. Ffolliott, H. M. Gregersen, and K. W. EASTER.1994. Policies for sustainable development:The role of watershed management U.S. Department of State, EPAT Policy Brief 6. Washington,DC. Brooks, K. N., H. M. Gregersen, P.F.Ffolliott, and K. G. Tejwani. 1992. Watershedmanagement:A key to sustainability.Pp. 455-487 in N. P. Sharma,ed., Managing the world'sforests: Lookingfor balance betweenconservationand development. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company,Dubuque,IA. P. F., M. B. Baker Jr., C. B. Ffolliott, Edminster, M. C. Dillon, and K. L. Mora, tech. coords.2000. Landstewardshipin the 21st century: The contributionsof watershed management.USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Proceedings RMRS-P13. FortCollins, CO. P. F., M. B. Baker Jr., C. B. Ffolliott, Edminster, M. C. Dillon, and K. L. Mora. 2002. Land stewardship through watershed management:Perspectivesfor the 21stcentury. KluwerAcademic/PlenumPublishers,NY. Gregersen, H. M., K. N. Brooks, J.A. Dixon, and L. S. Hamilton. 1987. Guidelinesfor economic appraisal of watershed managementprojects. United Nations, Food and AgricultureOrganization, FAO Conservation Guide 16. Rome, Italy. National Research Council. 1999. New strategiesfor America's watersheds.National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences, Washington,DC. Neary, D. G. 2000. Changing perceptions of watershed management from a retrospective viewpoint. Pp.167-176 in P. F. Ffolliott, M. B. Baker, Jr.,C. B. Edminster,M. C. Dillon, and K. L. Mora,tech. coords.,Landstewardshipin the 21stcentury:Thecontributionsofwatershed management. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Proceedings RMRS-P-13.Fort Collins, CO. Quinn, R. M., K. N Brooks, P. F. Ffolliott, H. M.. Gregersen, and A. L. Lundgren. 1995. Reducing resource degradation: Designing policy for effective watershed management. U.S. Department of State, EPAT Working Paper22. Washington,DC. R. J. 1998. Watershedmanagement: REIMOLD, Practice,policies, and coordination.McGrawHill Book Company.New York,NY.