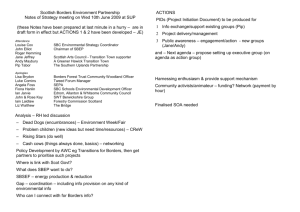

Annual Risk Analysis

advertisement