Document 11082212

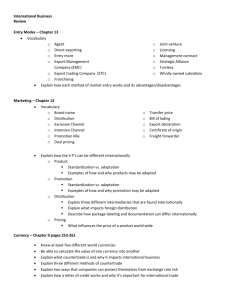

advertisement