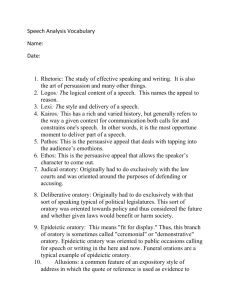

Quintilian on Rhetoric: Teacher & Pupil Conduct, Exercises

advertisement