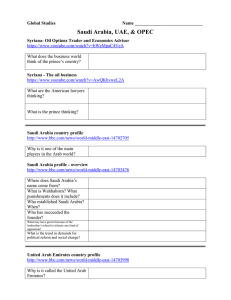

by OPEC M.A. Adelman 1992

advertisement