Document 11077001

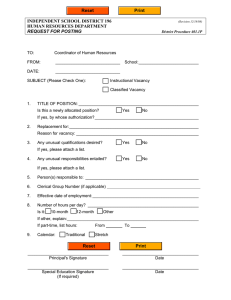

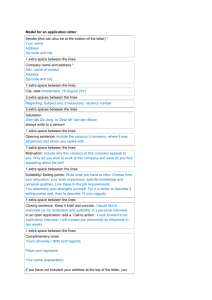

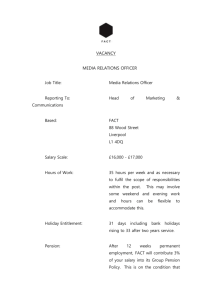

advertisement