Interdisciplinary Studies: in Anthropology, History and Geography presented on May 9,

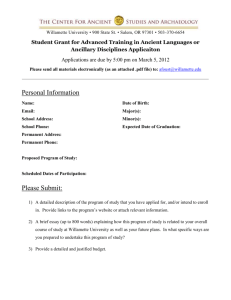

advertisement