Reducing Impact of Pulsed Power Loads on Microgrid Power Systems

advertisement

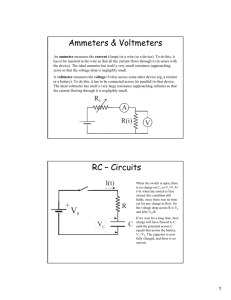

270 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SMART GRID, VOL. 1, NO. 3, DECEMBER 2010 Reducing Impact of Pulsed Power Loads on Microgrid Power Systems Jonathan M. Crider and Scott D. Sudhoff, Fellow, IEEE Abstract—Microgrid power systems are becoming increasingly common in a host of applications. In this work, the mitigation of the adverse affects of pulsed-power loads on these systems is considered. In microgrid power systems, pulsed loads are particularly problematic since the total system inertia is finite. Examples include ships and aircraft with high-power radars, pulsed weapons, and electromagnetic launch and recovery systems. In these systems, energy is collected from the system over a finite time period, locally stored, and then rapidly utilized. Herein, a new strategy to accommodate these loads is presented. This strategy is based on identifying the optimal charging profile. Using simulation and experiment, it is shown the proposed strategy is highly effective in reducing the adverse impact of pulsed-power loads. Index Terms—Marine vehicles, military aircraft, power quality, pulse power systems. I. INTRODUCTION M ICROGRID power systems with pulsed power loads (PPLs) are of significant interest in marine and aerospace applications. In these applications pulsed loads include high-power radars, electromagnetic launch and recovery systems, and weapons such as rail guns [1], [2]. Particle-accelerator and laser experiments are examples of pulsed loads in utility class systems [3]. It is often the case in such loads that a load specific energy storage element is charged over a finite interval of time, and then rapidly discharged. The charging of the energy storage device is an intermittent load which disturbs the power system [1], [4]. The power requirements of such loads can range from kilowatts to megawatts with a charge interval on the order of seconds to minutes [2], [5]. The discharge duration is normally much shorter, and is often essentially instantaneous compared to the charge interval wherein energy is accumulated from the power system [2]. The goal of this work is to minimize the system impact of these PPLs. Perhaps the most straightforward way to control PPLs of this type is through the use of limit-based control (LBC). The philosophy of the LBC is to charge the energy storage element as rapidly as possible subject to current and power limits. In [6], it is shown that the strategy is simple and effective; however, it is also rather disruptive to the system. Manuscript received September 10, 2010; accepted September 14, 2010. Date of current version November 19, 2010. This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research through the Electric Ship Research and Development Consortium under Grant N00014-08-1-0080. Paper no. TSG-00127-2010. The authors are with Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 USA (e-mail: criderj@purdue.edu). Color versions of one or more of the figures in this paper are available online at http://ieeexplore.ieee.org. Digital Object Identifier 10.1109/TSG.2010.2080329 Fig. 1. System schematic. One method to reduce the impact of pulsed loads is through the introduction of supplementary energy storage devices, such as flywheels [1], [4]. While effective, such an approach clearly adds mass and expense to the system. Another method to reduce the disruption caused by PPLs is through load coordination. In such an approach, the base load is shed in order to accommodate the pulsed load, so that the total system load remains constant. Such an approach is considered in [4], [6], and [7], and requires that adequate base load already exists, and that the base load is not critical. When these conditions are met, the strategy is effective. Clearly though, there are many cases in which these requirements are not met. As an alternative to LBC, auxiliary energy storage, and coordination strategies, a trapezoidal-based control (TBC) was set forth in [8]. This control was based on using a trapezoidal load profile. The parameters governing the shape of the trapezoid were selected so as to minimize the disruption caused by the pulsed load. However, this work assumed a priori that the trapezoidal power profile was the optimal shape. Herein, it is shown that this is simply not the case. Further, while the control set forth in [8] appeared effective in terms of simulation results, experimental results were not included. As an alternative, a generalized profile-based control (PBC) is proposed. In this scheme, it is assumed that there is a requirement to accumulate a set amount of energy from the system in a set amount of time. The control is designed to achieve these requirements in such a way as to cause a minimal disruption on the power system. The optimal shape for the power profile is derived, and is shown to be nontrapezoidal, as used in [8]. It should be observed that the proposed algorithm could be used in conjunction with auxiliary energy storage and coordination, if desired. In order to set the stage for the PBC, this work begins with a description of a nominal laboratory scale microgrid used to study a PPL on a microgrid system. This system is a subset of the medium-voltage dc (representative) testbed (MVDCT) [9]. 1949-3053/$26.00 © 2010 IEEE CRIDER AND SUDHOFF: REDUCING IMPACT OF PULSED POWER LOADS ON MICROGRID POWER SYSTEMS 271 Fig. 2. MVDCT PPL schematic. The PPL in this system uses capacitive energy storage, though the proposed control is not limited to this form. This is followed by a study of the nominal system performance, which uses an LBC scheme for the PPL, in order to provide context. Following the description of the nominal system performance the derivation of the PBC is presented. This development begins with the presentation of a metric to describe the disturbance caused by a PPL. This metric is then used to obtain an optimal power trajectory. A state feedback based approach to achieving this desired trajectory is then set forth. This is a critical step because it leads to robustness. The proposed control strategy is then applied to the laboratory-scale power system. Using both simulations and laboratory results the PBC-based PPL will be shown to be much less disruptive than the LBC-based PPL [6]. II. SYSTEM DESCRIPTION The microgrid power system used herein is depicted in Fig. 1. This system is designed to mimic a small portion of a shipboard power system. The system consists of a 59 kW generation system (GS-1), a 37 kW load representing a ship propulsion system (SPS), and a PPL. Descriptions, parameter values, and control schemes for the generation system and the propulsion system can be found in [9]. Fig. 3. MVDCT PPL. A. Hardware Description B. Control Description The circuit topology of the PPL is depicted in Fig. 2 and has two parts—an energy accumulation and storage circuit (consisting of an input filter, buck converter, and storage capacitor) and an impulse load. The input filter is designed to reduce the high frequency current ripple associated with the buck converter from entering the power distribution system. The buck converter regulates the current so as to charge the energy storage capacaccording to the desired profile. The impulse load is the itor application which actually uses the energy; the duration of this use is normally instantaneous compared to the duration of the charge cycle. Fig. 3 is a photograph of the experimental PPL. In an actual system, the energy storage capacitor could represent a physical capacitor. However, in the laboratory system, the majority of the energy storage capacitance is emulated to allow rapid discharge. The specifications, component values, and the control strategy for the capacitor emulator are defined in [6]. The PPL control consists of three layers. The outermost layer is the formulation of the charge and discharge commands. The next layer is the capacitor current control. This control utilizes the desired charge profile and creates a current command, . The innermost layer is the buck circuit hysteresis modulator which takes the commanded current and turns it into a switching signal for the buck converter. The charge and discharge control as well as hysteresis modulator are described in [6]. The capacitor current control will be described herein because it largely governs the interaction of the PPL with the system. In the nominal system, the LBC set forth in [6] is used. This control is shown in Fig. 4 where the output is a capacitor current command, The basic philosophy of the control is to charge the capacitor as rapidly as possible subject to a peak capacitor curand a peak power limit of . Inputs to this rent limit 272 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SMART GRID, VOL. 1, NO. 3, DECEMBER 2010 Fig. 4. Limit-based control. control are the target final capacitor voltage, the measured capacitor voltage, , and the charge status, . As can be seen, the measured capacitor voltage is first filtered by a low pass filter and then subtracted from the command. with time constant The voltage error is then multiplied by a proportional gain and limited to a dynamic limit which is calculated to insure that both the power and peak current limit will be observed. is selected to be large enough that the limit is Note that becomes very almost always in effect until the point where close to ; after this point the capacitor voltage approaches the target voltage asymptotically. For this reason the target voltage is set slightly higher than the minimum voltage to fire, . is high, the output of the gain/limiter If the charge status goes through an output filter to form the capacitor current command, . III. NOMINAL SYSTEM PERFORMANCE This section depicts the nominal performance of the system with the LBC scheme described in [6]. These results are presented for comparison with the proposed control scheme to be presented subsequently. In this study, the system is initially in steady-state with the s, a charging cycle is initiated. The SPS at full load. At goal is to charge the capacitor from 0 to 162 kJ in 23.2 s. Figs. 5 and 6 depict the results for the LBC based on time-domain simulation and laboratory experiments. Variables depicted include the PPL capacitor voltage , the PPL input dc voltage , the dc current into the PPL , and the current in the PPL buck converter output inductor . These variables are all defined in Fig. 2. The study parameters are as follows; V, V, kW, and A. These parameters were taken from [6]. As can be seen, the capacitor voltage ramps up nearly lins, early in time, although there is a slight inflection at which corresponds to the control switching from the capacitor current limit to the power limit. The bus voltage is seen to gradually droop during the course of the charge cycle; however, at the end of the charge cycle the bus voltage rises sharply and a pronounced peak occurs. The amplitude of this peak is 34.94 V (4.86%) in simulation, and 60.09 V (8.38%) in hardware. The input current can be seen to rise nearly linearly until the control Fig. 5. LBC transient study results (simulation). Fig. 6. LBC transient study results (hardware). enters constant power mode, at which point the input current becomes constant. The peak value of input current is 27.2 A. The inductor current can be seen to be essentially constant from the s, whereupon the curbeginning of the charge cycle until rent goes down as the power limit takes effect. CRIDER AND SUDHOFF: REDUCING IMPACT OF PULSED POWER LOADS ON MICROGRID POWER SYSTEMS As can be seen, the time-domain simulation results are generally consistent with the laboratory measurements, though ripple levels are somewhat different. Part of this discrepancy, particularly in the bus voltage, is attributed to oscilloscope descretization error. Other sources of error include non-idealities in passive component (eddy currents and light saturation of inductive elements) and possibly prime-mover response. 273 is the time rate of change of power is proposed. In (4), into the PPL. Before proceeding to explore the solution to this problem, it is convenient to normalize quantities of interest so that the results are readily scaled. Again using the approach of [8], the base energy will be defined as the desired incremental additional energy to be stored. Thus, the normalized stored energy is expressed (5) IV. DISTURBANCE METRIC AND NORMALIZATION Having presented results for the nominal system, it can be seen that the PPL causes significant disturbance to the system. In order to set the stage to reduce this impact, a metric to describe the disturbance is first introduced. For this purpose, the metric proposed in [8] is reviewed and utilized. A natural choice for a disturbance metric would be related to the bus voltage during and after the PPL charge cycle. However, the problem with such an approach is that the evaluation of the metric becomes not only a function of the PPL, but also of the system. Thus, for design purposes it is convenient to define a metric that is only a function of the PPL. The disturbance of a PPL on a system is related to its time and is referred to as power profile. This profile is denoted the power trajectory herein. The power trajectory must satisfy several constraints. First, the power trajectory must be such that the desired energy is obtained. Thus Next, time is normalized to the charge cycle period normalized time is defined (6) where corresponds to the start of the charge cycle. Finally, the base power is defined as (7) whereupon normalized power may be expressed (8) In terms of normalized quantities, (1)–(4) become (9) (1) where is the incremental additional energy to be stored in the energy storage element during the charge cycle, and is the period of the charge cycle. Note that prior to the charge cycle, the amount of energy stored is not necessarily zero. This . initial energy storage is denoted Second, it is desirable that the power trajectory is a continuous function of time. Thus it is required that (2) where is the set of continuous functions. This facilitates implementation in the presence of parasitics, and also limits the bandwidth of PPL disturbances on the system. By definition, a pulsed load is an intermittent transient load. Requirement (2) is thus coupled with the requirement that (3) Finally, it is desired that the system disturbance caused by the trajectory is minimized. In order to quantify this last point, observe that if the PPL were not pulsed, i.e., were a constant, then there would be no disturbance at all. Hence, one philosophy for a disturbance metric is to define the metric in terms of the time rate of change of the power trajectory. To this end, the disturbance metric (4) . Thus, (10) (11) and (12) respectively. V. OPTIMAL TRAJECTORY In this section, the metric defined in the previous section will be used to find the optimal power trajectory. As a prologue to this optimization, it is convenient to define the objective (13) Therefore, (12) becomes (14) Minimization of is exactly equivalent to minimization of but leads to a simpler development. Determining the optimal power trajectory is accomplished by minimization of the disturbance metric (14) subject to the constraints (9)–(11). It is claimed herein that the optimal solution to this problem is not a trapezoidal waveform as proposed in [8], but rather a parabaloid of the form (15) 274 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SMART GRID, VOL. 1, NO. 3, DECEMBER 2010 Substitution of (15) into (9) reveals that the constraint is satisfied. The continuity requirement (10) and requirement (11) are also clearly satisfied. It remains to be shown that (15) is the global minimization of (14). as a function which satisfies (11) To this end, define for but for which (16) With these definitions, it follows that any trajectory constructed as (17) Fig. 7. Normalized optimal power trajectory. will satisfy the constraints (9)–(11). By suitable choice of and any viable function for can be obtained. It will be shown herein that the optimal selection for is zero which implies that (15) is the optimum choice. From (14), and (17), (18) Expanding this integral yields ^ ) relationship. Fig. 8. Optimized trajectory P^ (E (19) (20) nonidealities including losses, initial storage, and passive component nonlinearities, it is advantageous to pose the optimal control law in a state feedback formulation. To do this, the most critical step is to determine what the power command should be as a function of the energy stored. , given by (15), the energy traTo this end, integrating jectory is readily expressed (21) (23) , (15), it can be seen that Returning to the definition for the 2nd derivative is constant, whereupon from (16), (21) must equal zero. Hence, (19) becomes and can be viewed paraThe relationship between metrically, and is depicted in Fig. 8. and anaIt is desirable to describe the relationship lytically. An exact, closed form solution has not been found. However, First, consider the middle term in the expression. Utilizing and basic calculus this term can be expressed as (22) By inspection, the global optimum of (22) occurs when either is zero, or when the integrand in the second term is zero (which is identically zero); in either case it follows implies that that is indeed the optimal solution for minimizing . Fig. 7 illustrates the normalized optimal power trajectory. (24) with and is an excellent approximation. The maximum power error between (24) and the ideal solution shown in Fig. 8 is 0.008. If additional accuracy is desired, using VI. TIME DOMAIN TO STATE MODEL CONVERSION At this point, the optimal power trajectory has been found as an open-loop function of time. However, because of a host of (25) with , , yields a maximum error of 0.0006. , and CRIDER AND SUDHOFF: REDUCING IMPACT OF PULSED POWER LOADS ON MICROGRID POWER SYSTEMS 275 Fig. 10. Optimal generalized waveform i command. Substitution of (29) into (31) and solving for the current yields Fig. 9. Error of (24) and (25) to actual solution. The power errors exhibited by (24) and (25) relative to Fig. 8 are shown as a function of normalized energy stored in Fig. 9. VII. IMPLEMENTATION where (33) The implementation of this strategy can be applied to a wide variety of PPLs and energy storage mechanisms. For the purposes of illustration, however, consider the case in which the , , , and energy storage mechanism is capacitive. Let , denote the energy storage capacitor voltage, the initial capacitor voltage, the final capacitor voltage at the end of the charge cycle, the capacitor current, and the capacitance, respectively. The objective is to formulate a capacitor current command so is stored in the capacthat an additional amount of energy itor over a duration, . The energy stored in the capacitor may be expressed as the amount of energy to In (33), the denominator is the capacitor voltage expressed in terms of and from (28). Thus, (33) could be used to calculate the desired capacitor current command. However, there are two practical problems with doing this. First, if the initial energy is zero the expression (33) is an indeterminate form when the energy stored is zero. If the initial energy is not zero then the initial current command is zero and the capacitor will not charge. In addition, because of losses and nonlinearities in the capacitance, it is possible that the desired final voltage will not be reached. These practical difficulties are circumvented by establishing and high energy threshold and a low energy threshold then calculating the current command as (27) (34) (26) From (26) and the definition of be added during the charge cycle (32) it follows that the normalized energy may be expressed (28) The normalized power command may then be calculated as (29) is defined by (24) or (25). The power into the cawhere pacitor is expressed (30) Equating the capacitor power with the commanded power into the PPL yields (31) This avoids numerical issues and ensures startup and charge cycle completion, although it does cause a minor deviation from the optimal trajectory. The resulting waveform for is depicted and range from in Fig. 10. Recommended values for 0.01–0.05 and 0.95–0.99, respectively. At this point, a control method derived from the metric to minimize system impact of the PPL has been presented. The control algorithm will now be demonstrated in the context of a laboratory scale power system. Fig. 11 depicts the final implementation of the control, which is based on (34). Like the LBC, the output of this control is . The inputs to the control are the measured capacitor voltage, (used to determine the energy stored), and the charge status, . As can be seen, the measured capacitor voltage is filtered then used to find the normalized energy stored using (28). The normalized energy is then used to determine a preliminary curusing (34). The output of the controller is the rent command 276 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SMART GRID, VOL. 1, NO. 3, DECEMBER 2010 Fig. 11. Modified control capacitor current command. Fig. 12. PBC transient study results (simulation). capacitor current command given by (34) or 0 depending on the desired charge status , which is high during a charge cycle and low otherwise. Fig. 13. PBC transient study results (hardware). TABLE I PEAK BUS VOLTAGE VARIATION RESULTS VIII. PBC SYSTEM PERFORMANCE This section depicts the performance of the PBC for the same study as the nominal LBC. The study parameters and conditions are the same; however, instead of charging to a defined capacitor voltage as in the LBC, the PBC defines an incremental addition energy value. To replicate the power and voltage levels of the LBC (for comparison), the following study parameters kJ, s, , are used. . Figs. 12 and 13 depict the study results for the PBC. As can be seen, the capacitor voltage can be seen to rise nearly linearly until the capacitor voltage approaches its final value. Once again, the bus voltage can be seen to droop during the charge cycle and rise at the end. Notice that the rise is significantly less than the rise in bus voltage due to the LBC. The amplitude of the peak is 14.46V (2.01%) in simulation and 19.56 V (2.74%) in hardware. The input current closely mimics the shape of the desired power trajectory. The peak value of input current is 22.5 A, approximately 5A less than the LBC. The final waveform shows the inductor current. The plateau and drop off between 40s and 43s is due to the high energy threshold in defined in (34). IX. COMPARISON OF LBC AND PBC Although the disturbance metric (4) is used as a basis to design the PBC control, it is interesting to compare the two systems in terms of the bus voltage variation. To this end, Table I summarizes the peak voltage variation which occurs for the LBC nominal system and the PBC based system. In both hardware and simulation the peak variation with the PBC is reduced to a value within the allowable range for peak dc voltage variation for ship power systems of 3.5% suggested in [5]. For a fixed energy accumulation, as the allowed charge time decreases, the system impact of the PPLs tends to become more pronounced. Fig. 14 depicts the results of the peak variation of the bus voltage from its nominal value for a range of charge periods for the two control schemes. As can be seen, charge periods of 10 s or less are very detrimental to the system bus voltage. The power levels created by the short charge periods of 10 s or less (on top of the SPS at full load) cause the generation system (GS-1) to surpass its rated power and therefore the bus voltage cannot be maintained. For charge times greater than 10 s the PBC method outperforms the LBC regardless of the charge period. These results further the argument for the improvement provided by the presented PBC method over the LBC method. CRIDER AND SUDHOFF: REDUCING IMPACT OF PULSED POWER LOADS ON MICROGRID POWER SYSTEMS Fig. 14. Peak variation in v versus T . X. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK The proposed PBC scheme has been shown to offer significant advantages over the LBC control with a similar level of implementation complexity. Although the PBC is formally designed to minimize a power disturbance metric, this minimization clearly lead to a significant improvement in the bus voltage. The advantages of PBC over LBC have been demonstrated using time-domain simulation and laboratory experiments. Suggested future work is twofold. First, it would be interesting to study the impact of the control on the prime mover. Secondly, the performance of the PBC coupled with load coordination controls such as proposed in [6] and [7] is of interest. REFERENCES [1] S. Kulkarni and S. Santoso, “Impact of pulse loads on electric ship power system: With and without flywheel energy storage systems,” in Proc. IEEE Electric Ship Technol. Symp. (ESTS 2009), pp. 568–573. [2] J. J. A. van der Burgt, P. van Gelder, and E. van Dijk, “Pulsed power requirements for future naval ships,” in Dig. Tech. Papers 12th IEEE Int. Pulsed Power Conf. 1999, vol. 2, pp. 1357–1360. 277 [3] H. Smolleck, S. J. Ranade, N. R. Prasad, and R. O. Velasco, “Effects of pulsed-power loads upon an electric power grid,” IEEE Trans. Power Del., vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 1305–1314, 1991. [4] L. N. Domaschk, A. Ouroua, R. Hebner, O. E. Bowlin, and W. B. Colson, “Coordination of large pulsed loads on future eletric ships,” presented at the 13th Electromagn. Launch Technol. Symp., Potsdam, Germany, May 2006. [5] M. Steurer, M. Andrus, J. Langston, L. Qi, S. Suryanarayanan, S. Woodruff, and P. F. Ribeiro, “Investigating the impact of pulsed power charging demands on shipboard power quality,” in Proc. IEEE Electric Ship Technol. Symp. (ESTS 2007), pp. 315–321. [6] B. Cassimere, C. Rodrijuez Valdez, S. Sudhoff, S. Pekarek, B. Kuhn, D. Delisle, and E. Zivi, “System impact of pulsed power loads on a laboratory scale integrated fight through power (IFTP) system,” presented at the Electric Ship Technol. Symp., Philadelphia, PA, July 25–27, 2005. [7] S. D. Sudhoff, B. T. Kuhn, E. Zivi, D. E. Delisle, and D. Clayton, “Impact of pulsed power loads on naval power and propulsion systems,” presented at the 13th Int. Ship Control Syst. Symp., Orlando, FL, Apr. 7–9, 2003, Paper 236. [8] M. Bash, R. R. Chan, J. Crider, C. Harianto, J. Lian, J. Neely, S. D. Pekarek, S. D. Sudhoff, and N. Vaks, “Medium voltage DC testbed for ship power system research,” presented at the IEEE Electric Ship Technol. Symp., Baltimore, MD, Apr. 20–22, 2009. [9] J. Crider and S. D. Sudhoff, “Reducing power system impact of pulsed power loads,” presented at the Electric Machinery Technol. Symp., Philadelphia, PA, May 19–20, 2010. Jonathan Michael Crider received the B.S degree in electrical and computer engineering from Northeastern University, Boston, MA, in 2007 and the M.S degree in electrical engineering from Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, in 2010. He is currently working toward the Ph.D. degree in electrical engineering at Purdue University. His interests include electric machines, power electronics, and genetic algorithms. Scott D. Sudhoff (S’87–M’91–SM’07–F’08) received the B.S. (with highest distinction), M.S., and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, in 1988, 1989, and 1991, respectively. He was an Assistant Professor at the University of Missouri, Rolla, from 1993 to 1997. In 1997, he joined the faculty of Purdue University, where he is currently a Full Professor. He has authored or coauthored more than 50 journal papers, including six prize papers. His current research interests include electric machines, power electronics, finite-inertia power systems, applied control, and genetic algorithms.