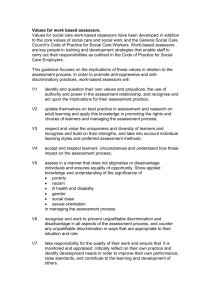

EXPERT EVIDENCE: the Kilmore East-Kinglake Bushfire Trial

advertisement

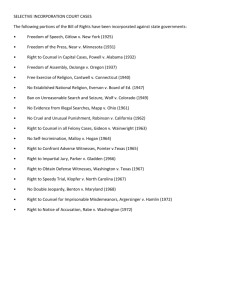

EXPERT EVIDENCE: the Kilmore East-Kinglake Bushfire Trial Jack Forrest, Supreme Court of Victoria April 2015 Legislative Background and Rules Order 44 Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 2005 (Vic). Order 23 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). Part 4.6 Civil Procedure Act 2010 (Vic). Key Aspects of Part 4.6 of the CPA Amendments to the CPA came into force on 24 December 2012: introduce Part 4.6 and relevant definitions into s 3 of the CPA. Parties must seek directions from the Court in respect of expert evidence as soon as practicable if intending to adduce, or “may adduce” expert evidence at trial (s 65G). Key aspects of Part 4.6 of the CPA The Court may give directions as to use of experts in both pre-trial and trial (s 65H and s 65K) and, particularly preparation of expert reports, the issues to be covered, limiting the number of experts, the appointment of experts, limitations on the scope of evidence and “any other direction that may assist an expert witness…” (s 65H). The Court has specific powers in relation to the preparation of joint reports and the conclave of experts in conjunction with a concurrent evidence session (s 65I). Key aspects of Part 4.6 of the CPA The “content” (presumed to be the discussions) of a conclave of experts must not be referred to at any hearing of the proceeding to which it relates, except that disclosed in the joint report (s 65J). Joint expert reports in relation to any matters not agreed may only be tendered at the trial in accordance with the rules of evidence and rules of the Court (s 65J). R 44.06(1) of SCR provides that at the Court’s discretion experts may provide joint reports setting out matters agreed and not agreed. Key aspects of Part 4.6 of the CPA The Court may give directions in relation to giving of evidence by expert witnesses at trial: direct expert witnesses to give concurrent evidence, provide an oral exposition of evidence, give an opinion of opinions given by other expert witnesses, to be cross examined or permitted to ask questions of other expert witnesses (s 65K). The Court may order the parties to engage a single expert jointly – which may then be tendered by a party at the trial (s 65L). Key aspects of Part 4.6 of the CPA A party may not adduce evidence of any other expert witness on any issue arising in proceedings if a single joint expert or court appointed expert has been appointed in relation to that issue (s 65O). Where a single joint expert/court appointed expert is engaged the parties must agree on written instructions to be provided and facts/assumptions of fact upon which the expert’s report is to be based (s 65N). The Court may appoint an expert to assist the Court or to report to it (s 65M) in addition to the special referee power (SCR Order 50) and the assessor’s power (s 70 SCA). However s 65M does not provide for the use that can then be made of a report provided by that expert. Concurrent Evidence: a Three Step Process 1. Early identification of the critical questions that need to be addressed and answered by the experts; 2. Conference between the experts without the involvement of practitioners, and a preparation of a joint report identifying areas of agreement or disagreement after the experts have exchanged their individual written reports; and 3. The giving of concurrent oral evidence by the experts after all lay evidence in the case has been adduced. Perceived Advantages of Concurrent Evidence Greater efficiency, particularly substantial reductions in court time and costs; Conferences between the experts and joint reports prior to trial inevitably limit the contested issues at trial and may lead to an early resolution; The ability for experts to comment on each others’ evidence allows for greater clarity and the clear identification of any disagreements; Experts give their evidence at a time when the critical issues have been refined and the area of real dispute has been narrowed to a bare minimum; Perceived Advantages of Concurrent Evidence Experts do not feel as pressured as in the usual adversarial contest; Peer presence can increase the objectivity and accountability of experts; It can eliminate lengthy and unnecessary cross-examination on matters that are not of any real importance; Judicial decision-making is facilitated because evidence on one topic is given by all experts at the same time and it is easier for courts to compare their evidence and to evaluate its weight or persuasiveness; and Parties retain the right to engage in cross-examination on key issues and, on matters of credit, if required. Perceived Disadvantages of Concurrent Evidence The necessity for judicial involvement early in the process; Personalities, particularly those which are dominant or forceful, may subvert the process Limitations on the ability of counsel to conduct the examination/cross-examination of witnesses; Unwieldy when there is a large number of witnesses; Arranging for witnesses to participate in expert conclaves and to give concurrent evidence; “Forcing experts to come to a shared position… could possibly undermine the veracity of the evidence given, to the detriment of one of the parties”; and “[Hot tubbing] is where you have a couple of experts who are encouraged to massage each other to get to a common position”. Kilmore East-Kinglake Trial Kilmore East-Kinglake Trial Fire took 119 lives, injured more than 1,000 people and destroyed over 125,000 ha of land in five municipalities, including much of the Kinglake and Strathewan townships Approximately 10,000 group members Claim settled for $494 million after trial concluded Settlement approved by Osborn JA in December 2014 Kilmore East-Kinglake Trial Claims against the electricity company for breach of common law and statutory duties, such as failure to replace the power line, failure to maintain the line, inadequate suppression devices, and inadequate inspection regime Claims against the CFA, DSE and VicPol for not giving timely warnings to residents in respect of the approaching fire Claims against DSE for not conducting sufficient planned burning Claims against asset inspection company for not inspecting the power line properly Kilmore East-Kinglake Trial Commenced 3 March 2013 208 days of trial Last day of trial 18 June 2014 26 counsel 100s of solicitors 26 pre-trial directions hearings 34 pre-trial in-court applications 83 general forms of order Kilmore East-Kinglake Trial 21,621 pages of transcript 40 expert witnesses 60 lay witnesses 400+ pages of pleadings 700+ pages of opening submissions 23,105 documents on the electronic court book 4000+ pages of closing submissions Pre-trial Management of the Expert Evidence: Case Management Conferences Working with the parties Providing guidance to the parties as to the running and operation of the conclaves Documents including: Development of ‘Procedure and Administrative Arrangements Protocols for Conclave’ Expert obligations Agenda questions Pre-trial Management of the Expert Evidence Arrangement of conclaves of expert witnesses, identification of topics/issues Division (if necessary) of conclaves into separate groups addressing particular topics/issues Use of court officers (in particular an associate justice) as moderators present throughout the conclave Production of joint reports identifying issues upon which agreement exists/does not exist Pre-trial Management of the Expert Evidence There were 11 areas of expertise on which expert witnesses gave evidence: Electrical engineering Materials engineering Lightening Asset management principles Analysis of vibrations and dynamics Probabilistic risk analysis Prescribed burning Fire behaviour Budget process and resources allocation Fire fighters; and Warnings. Expert Evidence at Trial Expert Evidence at Trial Concurrent evidence: – Joint reports, provided prior to the trial as a result of the conclave process and then questionnaires completed immediately prior to the session – Six concurrent evidence sessions – In one session, ten expert witnesses gave evidence – Preliminary rulings were given as to expertise and the application of s 79 of the Evidence Act 2008 (Vic) Expert Evidence at Trial Witnesses sworn in and adopt report(s) Order of questioning determined by the judge, depending on the topic and the diversity of opinion: usually the party calling the witness would commence by adducing any further explanatory evidence and the witness then cross-examined by opposing counsel Leading questions permitted, but may affect the weight to be given to the answer, particularly where the evidence is led from an expert called by that party Expert Evidence at Trial At the conclusion of the evidence on a topic: Experts given the opportunity to question each other. Each expert also given an opportunity to explain or enlarge upon any of the answers he or she has given. Re-examination generally not permitted unless the questioning by counsel involved: an attack upon the witness’ expertise; or an attack upon the credit of the witness. At the conclusion of the particular topic, the next topic is addressed in similar fashion. The Use of Assessors Prior to the trial, it was held that expert assessors should sit with the trial judge when hearing complicated expert evidence about fracture mechanics and vibration theory – which went to the heart of the plaintiff’s case about the cause of the break of the conductor. In Ruling No 32 [2013] VSC 630: (a) The assessors’ role is to assist the judge. The decision is that of the judge alone. (b) The assessors will sit with me during the concurrent evidence sessions. If they wish, they may question the experts (or counsel) in this context. Such questioning however will be limited to clarification of the evidence; that is, where they consider the evidence to be ambiguous, unclear or incomplete. (c) I may consult with the assessors while sitting if I find a point of evidence unclear and seek their immediate input as to an appropriate or useful inquiry to make. The Use of Assessors (d) I will consult with the assessors whilst in chambers on matters raised by the experts in their oral evidence and in their individual and joint reports. This may include advice as to any questions the assessors think I should ask counsel or the experts in order to determine the questions at hand. (e) I will seek the guidance of the assessors on technical matters upon which I lack the requisite knowledge to understand without qualified assistance. This may include “lessons” on matters fundamental to, for example in this case, fracture mechanics or vibration. (f) If the assessors raise a theory or opinion that has not previously been identified by the parties, I will discuss this with counsel. (g) The assessors may from time to time provide me with advice on matters over which there is dispute between the experts. Such advice is not binding and the determination of a particular issue rests with the judge. The Use of Assessors (h) I anticipate that I will consult with the experts immediately after the conclusion of the concurrent evidence session and, from time to time, while drafting the judgment. This is likely to include seeking confirmation from them that I have properly understood the meaning of the expert evidence of conclaves 1, 3 and 4. I repeat, however, that their role is confined to providing advice and ensuring that I have comprehended the evidence given. I also repeat that the decision on these issues is mine and mine alone. At the trial, I was assisted by two assessors – both professors of engineering with vast experience in fracture mechanics and vibration. They sat with me for approximately one month during the course of the largest and longest of the concurrent evidence sessions.