Document 11070353

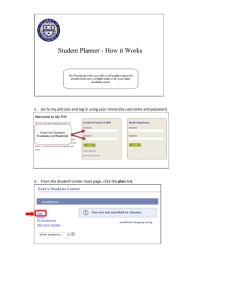

advertisement