Document 11070325

advertisement

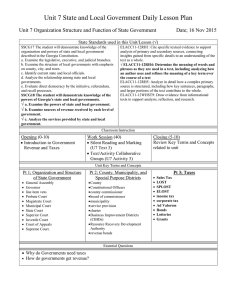

rifci biorv^nr '!i:J^£^ ALFRED P. WORKING PAPER SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT OUTWARD BOUND: STRATEGIES FOR TEAM SURVIVAL IN THE ORGANIZATION DEBORAH GLADSTEIN ANCONA APRIL, 1989 WP //: 3006-89-BPS MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 50 MEMORIAL DRIVE CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139 JMASS. MAY iN!^T. TECH. 4 1989 OUTWARD BOUND: STRATEGIES FOR TEAM SURVIVAL IN THE ORGANIZATION DEBORAH GLADSTEIN ANCONA APRIL, 1989 WP //: 3006-89-BPS I would like to thank Lotte Bailyn, Connie Gersick, Debbie Kolb, and Ed Schein for their helpful commentary. ABSTRACT Using the external perspective as a research lens, this study examines team-context interaction in five consulting teams. The data show three strategies toward the environment: informing, parading, and probing. Probing teams revise their knowledge of the environment through external contact, initiate programs with outsiders, and promote their team achievements within They are rated the highest performers, although member the organization. satisfaction and cohesiveness suffer in the short run. Results suggest that external activities are better predictors of team performance than internal group processes for teams facing external dependence. Teams are in the midst of a Although teams(l) renaissance (Goodman, 1986). are hardly new organization phenomena, the recent emphasis on teams as a fundamental unit, of the organization structure is different (Drucker, 1988). Perhaps we finally are taking groups seriously. Whether it is newly created teams to service financial accounts at Goldman Sachs (Maister, 1985), or to develop new products at General Motors and Procter and Gamble, or to implement new manufacturing strategies in the aerospace industry (Kazanjian & Drazin, 1986) this new and different form of group is proliferating (Gersick, 1988). One difference is in the increased amount of autonomy and responsibility granted to the team in an attempt to achieve flexibility in a competitive, rapidly changing marketplace (Ancona & Caldwell, 1989; Kanter, 1983). A second change is the increased use of cross-functional teams, groups put together to accomplish a particular task through part-time members who have concurrent commitments to other parts of the organization (Galbraith, 1982). Finally, in response to new environmental challenges, teams are called upon more and more to span traditional boundaries both inside the firm (providing a closer coupling among diverse functional units) and outside the firm (providing a link to customers, suppliers, or competitors) (Clark & Fujimoto, 1987; Von Hippel, 1988). This study tracks the development of some of these new, part-time, more autonomous, and externally-oriented, teams. Using a framework called the external perspective (Ancona, 1987), this research examines the on-going relationship between five consulting teams and their environment. The environment includes both the organization in which the teams are situated and those outside the organization that are serviced by the teams. A secondary interest is examining the relationships among external activity, internal team activity, and subsequent team performance. THEORY Both social psychology with its emphasis on group process, and organization design which views teams as analyze team behavior. form. (2). a structural form, seem appropriate frameworks to Yet both may have limited application to this new team Group process models have tended to treat the group as a closed system This is particularly true of the humanistic and decision-making schools which rely on laboratory and training research where group context is controlled in order to obtain a fine-grained analysis of internal group activity (Gladstein, 1984; Goodman, 1986; Hackman & Morris, 1975). However, organization teams, charged with the task of spanning traditional boundaries, are open systems requiring complex interactions with people beyond their borders. For this reason it is important to extend our theoretical lens from the team boundary outward. Organization design models view teams as a vehicle to manage uncertainty and interdependence that is not adequately handled in the organizational hierarchy (Galbraith, 1977; Tushman & Nadler, 1988). Unlike the group process models which focus on the activities of free actors, organization design models focus on structural constraint. The team is viewed as the solution to a design problem and hence there is an implicit assumption of structural determinism; the structure will direct team behavior to meet uncertainty requirements. Yet there is mounting support for less extreme models in which "there is no sense in which structure determines action or vice versa" (Giddens, 1984; p. 219). According to Giddens, there are clearly constraints on action brought about by structures, but actors can make a difference. Therefore, analysis of behavior using this model monitors the interaction between activities and conditions in the environment. Structure is both constraining and enabling, and patterned action becomes structure. For the study of teams this suggest monitoring team-environment interaction, and mutual influence over time. The External Perspective In contrast 'to traditional models of group process the external perspective looks outward from the group boundary. The focus shifts to the group in its context, and the group is assumed to have an existence and purpose apart from serving as 1986). a setting and apart from the individuals who compose it (Pfeffer, The question is no longer "How does the group influence individuals?" but "How does the organization influence the group?" individuals build a Rather than "How do cognitive map of the group?" the question is "How do group men±>ers map and reach out to their environment?" Following Giddens (1984) structuration model however, the emphasis is not solely on team initiatives or environmental influence but on the interplay between team and environment. Finally, internal team activities are not ignored, but rather than studying decision making or roles per se, our interest is the internal processes that influence, and are influenced by, those in the environment (Ancona, 1987). There has been partial application of the external perspective in groups (3). One study of a hundred sales teams shows that team members conceptualize group process as two separate sets of activities: intragroup activities and cross-boundary activities to coordinate work with outside groups (Gladstein, 1984). A series of other studies have documented a variety of external activities and roles that link teams to their environment. For example, studies of research and development teams have documented boundary spanners, stars, and gatekeepers, who import needed technical information from outside the group (see Allen, 1984; Katz & Tushman, 1981; Tushman, 1977; 1979). In a study of new product teams Ancona and Caldwell (1988) show that groups use external contacts not only to obtain technical information, but also to create a mapping of resources, support, and trends in the organization, to influence those with resources, and to synchronize work flow. Gersick (1988) moves beyond description of specific external activities to a process model of interaction with the environment. In a study of eight temporary task forces, she finds that groups respond to feedback and information from the environment only at certain points in their life-cycle. The group can be influenced at the first meeting when basic approaches to work are set up, and at a midpoint transition when the group is looking for outside feedback to reformulate an understanding of external demands and how to meet them. In contrast, the two major phases of work activity (from the first meeting to the midpoint, and from the midpoint to completion) are closed periods when the group is not likely to alter its basic direction (Gersick, 1988; Hackman & Walton, 1986). This paper extends Gersick' s approach to studying the on-going interaction between teams and their environments. Gersick has identified a pattern of interaction, here we seek to identify the specific content of that interaction. For example, we know that in the first meeting basic approaches to work are set up, but we do not know what those approaches are. This research searches for the strategies that teams in context use to manage the tension between internal and external demands. that the environment influences the group. We know from Gersick' s research This research aims to understand what part of the environment influences the group, how it does so, and how the group in turn influences the environment. performance as a Finally, this research adds group key variable in order to generate normative propositions. Extensions of the External Perspective We know from previous research that groups develop norms about their task, interpersonal behavior, and group-context interaction quickly, sometimes in the first few minutes of their first meeting (Bettenhausen & Murnighan, 1985; Gersick, 1988; Schein, 1988). Team members bring scripts--sequences of activity to follow--developed from other group experiences to apply to the new group situation •<Abelson, 1976; Taylor, Crockcer & D'Agostino, 1978). words, a group is not a tabula rasa In other Existing scripts include both implicit . and explicit strategies that will guide the early actions of the team (Bettenhausen & Murnighan, 1985). This research seeks to document those strategies relating to the external environment. Internal interaction can be categorized along a number of dimensions, e.g., autocratic, consultative, or democratic (Vroom and Jago, 1974). The goal of this research is to derive some dimensions that can be used to describe group behavior with the external environment. and closed, to describe whether or not Researchers have used the terms open a group's boundaries are permeable to external transactions (Alderfer, 1976; Ancona & Caldwell, 1988), but my goal is to specify a more developed, empirically based, model of external interaction. A second goal is to develop an understanding of the role of the environment in interaction with the teams. The environment is said to influence a group by providing feedback about how well the group is meeting its demands (Gersick, 1988). But how does this influence occur? is diverse and has disparate demands What happens when the environment (Tsui, 1987)? What if parts of the environment have vague or unclear demands--can those demands then be shaped by the group? Going back to Giddens (1984), and the debate between strategic choice and environmental determinism (Astley & Van de Ven, 1983), this research investigates both the nature of the constraints imposed by the environment and how teams can make a difference. Finally, we still know very little about how external activity relates to internal activity and performance. Most texts designed to help a team function effectively emphasize internal activity. Priorities tend to include establishing norms of how to work together, agreeing on expectations for group member input and performance, and setting boundaries between the individual and the group around issues of intimacy and authority (see Bales, Schein, 1988). Yet, 1983; Dyer, 1977; from an external perspective, teams that manage their external dependence and are able to obtain critical resources become better performers (Pfeffer, 1972; 1986; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). These divergent views of the precursors of performance raise two fundamental questions: What is the nature of the interaction between developing an internal mode of operation and external one, i.e., do the two occur simultaneously, and does the development of one interfere with, or facilitate the development of the other? Finally, which set of activities, internal or external, are most predictive of performance? PROJECT HISTORY Early in 1982 a state education commissioner decided to restructure his department to improve coordination among divisions, to provide more uniform service across geographic areas, and to improve the reputation of the department in the field. He hired several faculty members from a New England business school to help with this reorganization. I taught some organization structure concepts to a cross-level design team in the department. created several design options to present to the commissioner. structure, I Members Once he chose a was permitted to monitor the new teams. The New Organization Structure The original organization was along functional lines, with consultants (e.g., reading specialist) reporting to one of six division heads in areas such as elementary, vocational, and special education. The new department structure has consultants "reporting" both to a functional unit head and to a regional team leader (see Figure 1). "Reporting" is somewhat of a misnomer, for team members are at the same hierarchical level as leaders, although leaders have more responsibility and receive teams' a small, additional, stipend. The regional act as generalists to diagnose, and serve the needs of their regions, and to improve interunit coordination. Thus, team members might go into a school district and interview teachers about their needs for curriculum change, then put together a new course design to meet those needs using the varied resources of the department. The vice commissioner (VC) supervises the activities of the regional teams, while functional unit chiefs report to division heads who report to the commissioner. The head of human resources has the role of resource, facilitator, and evaluator of the new design. Implementation In the Fall of 1982, when the design had been selected, the VC, the commissioner, and the head of human resources, chose regional team leaders from a set of inside consultants who had applied for the position. consultants to teams. Assignments attempted to create cross-functional teams, with members of roughly equivalent interpersonal skills. assigned to a They also assigned Each team was geographic area. Once the leaders had been chosen, Walter, the leader of the W team, scheduled informal meetings of the team leaders so that they could act as sounding board for each other. a These meetings were forbidden when the VC found out that such meetings were taking place without him. In late December the entire department met off-site. a The commissioner gave supportive speech, and the staff who had helped to design the new structure put together skits to illustrate how the new organization would work. the teams were created. And so Teams had to decide how to "serve the needs of their regions" and allocate members' time between team and functional activities. Team leader meetings were formalized and run by the VC. In January and February of 1983 the teams began to generate plans on The commissioner then decided that he did not want each serving their regions. team to do different things, so he told the leaders to plan a unified approach. When a few weeks went by and he saw no results, he told the teams to create profile of their regions and to develop a a workshop to communicate "promising practices" observed in particular schools to the rest of the region. From research point of view, these regional teams are exemplars of a group given a general task with part-time members are new , the organization. with autonomy to complete that task as they like, and external demands they must define , , a new a . Specifically because the teams role and learn to function with existing parts of Members must work inter dependent ly to produce a service of importance to the organization. and well-defined group boundaries There is formal leadership within the team, Teams are evaluated by upper levels of . management, and they serve the needs of an external constituency. Hence, field is open for teams to define both internal and external behavior. the This paper traces how they did that and how they performed. METHODOLOGY The exploratory nature of the research led to an inductive study of the external activity in five teams' natural environment. Most consultants, who came from a variety of units, knew each other by sight but had never worked Their new task was serving school districts in given geographic together. areas. Teams ranged in size from six to ten. Data Sources Using a multi-method approach, of their existence. I followed teams for the first five months Data collection focused on three sets of variables that provided information to answer the research questions. First, data on team-leader plans were collected right after the teams had been formed. Interviews were designed to ascertain implicit and explicit strategies toward the environment. Given time restraints, I chose team leaders to interview under the assumption that they would have the most influence over team norm formation. Second, I monitored interaction the team had with outsiders using questionnaires, logs, interviews, and observation. Key actors in the teams' environment were the task allocators and performance evaluators within the organization (the commissioner and VC) and those outside the organization who were the recipients of team services (superintendents of school districts). Third, I assessed internal group process and outcomes to gauge the interaction of internal process, external process, and effectiveness. Team satisfaction and cohesiveness data were collected as were performance ratings made by outsiders. These external ratings were collected later on in order to allow for the lag effects between process and performance (Gladstein, 1984). Team Leader Strategies. In early January 1983, about their plans for the teams, using a I interviewed team leaders semistructured format. Interviews lasted from one to two hours, and were tape recorded, then transcribed. The first set of questions were general ones about initial team goals and anticipated early leadership and team activities. The intent was not to prompt issues about external interactions, but to assess whether these issues were brought up at all. The second set of questions probed for specifics about external activity; was any planned, with whom, of what type? Team-Context Interaction . In order to monitor interaction from January through May, questionnaires, logs, observation, and internal documentation were used. First, a questionnaire was distributed in late February to all team members. Questions were taken from several sources: Hackman, 1982; Van de Ven & Ferry, 1980; and Gladstein, Questions addressed interaction with the 1984. regions (difficulty in predicting the needs of the region), and interaction with the commissioner's office (difficulty of figuring out management expectations, team and organizational goal congruence, and amount of communication with upper levels in the organization). required to rate items on 5-point Likert scales. Respondents were All team members received questionnaires with envelopes for direct return to the researcher. questionnaires were returned for a Seventeen response rate of 47%. Second, all team members kept a log of the number of personal visits to each school district. The head of human resources required that this log be kept as input into the evaluation of the new organizational design. reported on Data are two-month period. a Third, the author and a research assistant, both observed team meetings throughout the five-month period (an average of 2.4 meetings per group). The author alone sat in on seven out of the nine team leader meetings and met several times with the commissioner and VC to get their reactions to team progress. Notes taken during meetings aimed to capture both how teams discussed their environments and how they organized themselves to meet external demands. Beyond this general goal, note-taking followed an open-ended technique using three columns: observations, interpretations, and patterns (see Hanlon, 1980). Finally, throughout the entire period, we asked team leaders to send us agendas, minutes, notes, and other written material originating in their teams, which helped us to track team events. Team Performance. outsiders. Team outcomes were assessed both by team members and The February questionnaire required assessments of group cohesiveness and member satisfaction. In May, 10 right before our observation ended, we interviewed a member of each team selected at random. This interview was open-ended, focusing on evaluations of the team's strengths and weaknesses, major activities, and areas for improvement. The following January the author met with the commissioner and the head of human resources (the VC had left the organization) for evaluation of the teams a year after their formation. I asked them to rank order the teams along the same dimensions used in their formal evaluations of the teams and to explain their rationale. Superintendent ratings of the teams had been obtained by the head of human resources and were given to me. She had sent out surveys asking whether the team structure had resulted in better, worse, or the same service as the year before. Data Analysis Inductive research does not follow an established format of analysis (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Yin, 1984). a tracking, multi-method approach. In this study I used what might be called The analysis had three components: 1) content analysis of team leader plans to determine strategies, 2) development of team profiles assessing internal process and team-environment interaction, and later performance, and 3) assessment of proposed relationships among the key constructs. Deriving Strategies. Once the interview data were collected from the team leaders, the author and research assistant reviewed the transcripts and listed all references to planned interaction with outsiders on index cards. We also recorded references to what might be called non-interaction,- for example, a leader might speak of not wanting to respond to initiatives from outsiders. Included were references both to interaction that the group would initiate and that outsiders would initiate. Finally, we recorded plans for internal group activity because this, too, was part of the leader's overall strategy. 11 For example, if the key goal for one team leader was fostering communication within that told the team while it was building a reputation in the field to another, us something about internal versus external priorities. Once we had index cards for all five groups we coded each entry on the Then we dimensions it seemed to represent, e.g., frequency of interaction. This lead identified similarities and differences among the stated approaches. to the grouping of teams into three categories, representing different strategies toward the environment, that will be explained below. Developing Profiles. Based on the activities of the teams, we developed team profiles--short summaries of key processes and performance. In developing the profiles we were most interested in team-context interaction, particularly with respect to the commissioner's office and the school districts. We kept a log of all documentation from the project and whenever we had about twenty-five new entries we would each review them and discuss how team profiles needed to be changed. In cases where we disagreed, we tried to understand why, and to determine if additional data could help to clarify the issue. From here the design evolved. a Viewing research as a cognitive, rather than validation, process we continuously alternated between concept formulation and data collection (Bailyn, 1977). In the first few weeks of the new design, team meetings were often sporadic, and considerable information was passed along between meetings. A questionnaire seemed required to tap into member perceptions of external interaction that were not mentioned during meetings. In the case of a particular team with infrequent meetings and the lowest survey When we response rate, we set up an interview to fill in missing information. found that the most information about team activities was communicated during team-leader meetings and then transmitted throughout the organization to attend as many of these meetings as possible. 12 In particular, I decided the April meeting was coined the "show and tell" meeting because team leaders had to report on their teams' progress to date. In putting together profiles, however, we focused on process and performance information that was corroborated by another source. We tried to get independent assessments of what was going on from multiple individuals through multiple methods, e.g., member interviews, management rankings, and superintendent assessments. as a "problem" team, In one example, the commissioner spoke of one team and team meeting and interview data supported this. In another instance, however, the commissioner noted another team seemed to be doing very little, while the team leader and members saw themselves as very busy and productive. Conflicting reports became part of the data base. We also tried to get parallel data from each group, independent of its early categorization; not knowing whether a team would follow its leader's plans we did not want to reify the strategies. Assessing Relationships. We now had data on team strategies, actual interaction patterns, and performance. What emerged from numerous discussions and immersion in the data are some proposed relationships among these variable sets that await testing by future researchers. RESULTS Team Leader Strategies Our analysis of team leader plans suggested three different strategies toward the environment. A strategy of informing involves concentration on internal team process until the team is ready to inform outsiders of its intentions; a strategy of parading consists of internal team building but simultaneously being visible in order to let outsiders know that members know and care about them; and a strategy of probing stresses external processes and requires team members to have a lot of interaction with outsiders to diagnose 13 their needs and experiment with solutions to meet those needs. An example and analysis of each type will explain this further. Victor: A strategy of Informing The first goal is to foster sensitivity to opening communications. Goals We have to struggle with this nebulous goal, struggle with the mechanisms of how we are going to function. This must be done before anything else. I'll be laid back and let people work, as opposed to being Leadership. I'll be a facilitator and supportive. My authoritarian and directive. greatest task will be to keep up the enthusiasm of the group. Interaction With the Districts. We need to build our understanding of each other and the districts that we are working in--share our experiences and gather some information about the needs in our territory. We need to gather information, talk about it, digest it, and decide if it is important or not. At first we may have to sift through some very unimportant information until we Somewhere along the get a feeling for the kinds of things that are important. line we are going to need a lot of input and a lot of exchange of information back and forth between the department and the local level. We will want them (the teachers and administrators in the school districts) to know about school approval (one of the designated interventions in the district) long before we implement it. Walter: A Strategy of Parading Goals. Develop a team understanding of what we are about, the matrix concept. Make them comfortable wearing those shoes, comfortable working with each other. Then it will depend on the regions--we won't hit those that are most hurt, but go after major needs that most have. My job is to get Leadership. To facilitate, coordinate, inform, smooth. the job done within the region, a team member's job is to understand the matrix and work within it so we all function as a smooth operating group. Interaction With the Region. Develop a regional profile, sharing information that we have--the information and perspectives that we have about each of the districts; put that together and synthesize it so that we know what our region looks like. Be visible. Let them know that we are here, but stay away from crises dropped in our laps. Develop our priorities and let them know what we want to do. Yurgen: A Strategy of Probing Goals. I think the first requirement of a team is to become fairly familiar with the region to which they have been assigned. Leadership. I probably have the prime responsibility for selling this 14 concept to the local leadership, superintendents, principals, what have you. Everyone has got to be involved, but I have the most direction. I think it is going to take a major effort to Interaction with the Region. gain credibility- and the methods used are going to have to be tailored to each district. The first task is to get them to express their needs for services. Sell yourself to these people: this is what we can bring you, tell us what your needs are and we will design something to address those. If we do not do this we lose our customers. We have each been operating in our own sphere so even though I have knowledge of every district up there, I have been looking at it from one point We all need to broaden our perspective and see what they see their of view. needs to be. One of the striking differences among team leader strategies is their view of when and how to interact with their regions. Victor's strategy of informing has a primary goal of creating an enthusiastic team with open communications among members, and clear group goals. Initially, the level of outside contact will be low (only "somewhere along the line" does Victor anticipate a lot of interaction with the field) . Even when Victor discusses interaction with the districts, he speaks of "sharing our experiences," i.e., the data we already have, and the need to "sift through ... information," i.e., reference data that is written and stored, rather than newly collected. Furthermore, judgment about what is important in the field is made by the group "deciding if it is important or not," and only later communicated to the districts: "we will want them to know about school approval long before we implement it." In short, this team will inform outsiders when it decides what its approach will be. Walter's strategy of parading (to march or walk through or around) adds to the emphasis on internal team building the need to go out and be visible in the field. Like Victor, Walter wants his team to work on becoming a "smooth operating group," and like Victor, he sees his team as mapping the environment, or "figuring out what our region looks like," by using data that team members already have. Similarly, Walter plans to have his team develop priorities that In fact, Walter intends to stay away are then communicated to the districts. 15 from the communications initiated by the districts; "crises dropped in our laps" that may move the team away from what they plan to do for the majority. In contrast to Victor, however, Walter plans a higher level of interaction in the field in order to be visible, and to "let them know we are here". This notion of external visibility or parading, is even more vividly explained by Xena, who shares this strategy: Find out Try and visit all the superintendents, and visit all the schools. time. out each team member of the different Take a about their unique styles. want region, I my every building in I've in been I want to be able to say that be and meetings superintendents' to circulate, to be familiar, to go to introduced to improve my reputation. People should feel comfortable calling us and getting help." While Xena does not mind, and in fact, welcomes, the external initiatives of those in need, her team's initiatives into the field, like Walter's, are to be aimed at obtaining visibility and familiarity. This goal of visibility differentiates the parading from the informing strategy. Yurgen's strategy of probing calls for high levels of two-way communication with the external environment, not solely for visibility, but to broaden the perspective of team members, to diagnose the needs of the regions, to obtain feedback on team ideas, and to "sell" the services of the team to the "customer". Yurgen, in contrast to all the other team leaders, sees external He does not believe that his team activity as the first and primary goal. members currently have all the data they need to put together a plan for the region. They have information about the districts, but that information is limited in that it has been obtained using a different frame or mindset: "I have been looking at it from one point of view" (in this case as a specialist rather than the new role of generalist and consultant). Yurgen plans to promote a new viewpoint through a very interactive approach to the environment. The interaction consists of hearing the needs of the region as expressed by people in that region, "get them to express their need 16 for services," then testing whether the team's plans to meet those needs are adequate. The model here is of a salesperson creating a customized product who wants to make sure to select the options that will satisfy the customer. Zoro, the other leader in this study who plans a probing strategy, envisions this same widening of team member perspective, and reciprocal give-and-take communication with the environment. .We Can we move people from their vertical position to being generalists? definitely need to go to the districts and talk to teachers, principals, administrators, and board people and say to them, "Are things different now? Are things better? Are you being serviced better over the total educational picture?" We want to be more visible, and we want to find out their needs and develop strategies to meet those needs. We are going to attend the regional Then we will visit superintendents in their home superintendents' meetings. districts and talk to the leadership. We'll establish key personnel and set up communications channels. We have to become a team and I think that as a result of the Z team getting We want to know a region we will get a chance to interact with other members. to get to know our regions and we want them to get to know us, so that the idea of a team is not just a term but a reality. . . It is clear from the outset that team leaders envisioned diverse strategies toward the environment. amount of interaction , These strategies differed on several dimensions: 1) or how much interaction with the field would occur--a lot or a little; 2) method of information gathering about getting data to put together a , or how the group would go map of the external environment--either use information that members already had or go out into the field and seek new information; and 3) type of interaction , or the way in which men±>ers would approach the environment- -inform the field of the team's intentions, parade about so as to get to be known and be able to observe the environment, or actively probe and test plans with those outside the team. Table 1 reports our assessment of where each group falls on these dimensions. In short, a strategy of informing (Victor) involves plans for low levels of interaction early on, but more later when outsiders would be told of the team's 17 decisions. A strategy of parading (Walter and Xena) includes plans for a lot of external interaction for the sake of visibility in the environment. Regional plans f-cr teams following these two strategies would come from information that team members already had, or that could be obtained in the department. A strategy of probing (Yurgen and Zoro) , by contrast, would mean a high level of interactive contact with the environment to revise team knowledge of the region and meet customer demands. Strategy Implementation Despite the best laid plans of mice and men.... While the last section identified the different strategies that team leaders had for their teams, here we report on the actual interaction between teams and their regions and the commissioners office, as well as internal processes. Victor, A Strategy of Informing The questionnaire data, log data, interviews, team meetings, and observation all indicate that the V team, in fact, had little interaction with the external environment, resulting in its inability to diagnose the needs of the region or top management. Internal processes were highly conflictual. Throughout the observation period the V team did not do very much informing; it maintained an internal focus. The questionnaire data indicate that the V Interaction with the Region. team had a hard time early on figuring out the needs of its region, while the log data show that it made fewer visits to the region than any other team (see Table 2). (N=l), The V team also had the lowest response rate to the questionnaire so we interviewed a team member in March. interaction with the regions was a She indicated that problem, reporting that "there are few requests from the schools, and so team members have not gone to visit schools." In May, another team member reported that team members had gone to 18 Superintendent meetings, but "just to listen, not to exchange ideas." Interaction with the Commissioner's Office. Table 3 reports on the questionnaire items assessing interaction with the commissioner's office. The V team has the lowest scores, indicating that members had a difficult time determining management expectations, formulating team goals that are congruent with organizational goals, and communicating with the commissioner's office. The two interviewees expressed a negative view of the coirunissioner and organizational red tape. One team member reported that at the last meeting Victor was heard to say that the commissioner constrained group activity and that meetings with the VC were a waste of time. In April, during the "show and tell" session, Victor reported difficulty in gaining group member commitment. The commissioner heard that Victor was having problems and asked if he could help. Soon after this meeting the Commissioner began to refer to Victor's team as the "problem team," a label that had gained wide acceptance throughout the organization by May. Internal Process. Victor's major goal had been to create effective internal communication and to clarify within the team the nebulous goals that had been handed down. Team observations, however, indicate that the V team experienced many meeting cancellations attributable to poor attendance, poor meeting preparation, high levels of conflict, and challenges to Victor's leadership. At the May meeting, team members angrily called for outside facilitation or rotating leadership. Walter and Xena, A Strategy of Parading Although Walter and Xena planned to be very visible, parading does not describe them fully. The W team did not parade in the regions; it had little contact with the regions, did not initiate programs, and mapped the environment from existing member knowledge. The team did have a high level of 19 confrontation with the commissioner's office. The X team was very visible in the regions but remained relatively isolated from top management. Both teams had smooth, internal processes with efficient problem solving. Interaction with the Regions. The questionnaire and log data show very different patterns of interaction with the region for these two teams (see Table 2). The W team had scores resembling the informing team, in that there was difficulty in predicting the needs of the region and low frequency of interaction with the school districts. In contrast, the X team reported good prediction of regional needs and made more than twice as many visits to the school districts. A final interview with a member of the W team in May suggested that its low level of interaction with the school districts was a result of Walter's notion that the superintendents already knew the department so it was not necessary to waste their time with meetings. The respondent noted some frustration on the part of team members because "the field is waiting (for us) and we're waiting to be told (by top management) what to do out there." Xena and her team members were actively involved going out in the districts and sitting in on meetings. There was also some assistance given to an elementary school project as early as February. One team member questioned the value of going to superintendent meetings because they addressed district, not team, agendas. Nonetheless, the X team was more active in going out into the field than the previous teams were, and Xena met her goal of visibility. Interaction with the Conunissioner ' s Office. The data indexing interaction with the commissioner's office are more difficult to interpret. The W and X teams fall between the informing and probing teams on their ratings of how hard it is to determine management expectations, on making group goals congruent with organization goals, and on communicating the ideas and concerns of team 20 members upward (see Table 3). Team W has better scores than team X, but other data sources tell of a very different type of relationship between each team and the commissioner's office. The W team was quite vocal in its irritation with top management. Walter had been the one to set up the eventually banned team leader meetings, and he became very outspoken in his continued resentment over intrusion from above. Fighting for the power he thought the teams ought to have took up a lot of his time and energy. He chaired the first two "official" team leader meetings and challenged the VC numerous times, e.g. "How did this deadline get established when we were not asked about it?" throughout our observation. Walter's statement, "We are adults and want to solve our own problems..." became tenure as team leader. Conflict between the two persisted a theme that Walter carried throughout his W team members also exhibited some resentment toward the commissioner, with one interviewee complaining about the "mindless tasks" that the commissioner assigned. In contrast, Xena, whose team was very visible in the districts, played a very minor role inside the organization. and missed several of them. still waiting for direction. She was quiet at team leader meetings Yet when we left in May, Xena and her team were She also was annoyed at the intrusion of the commissioner in the team's affairs, yet wanted to be told what to do. Both the W and X teams placed team building as a high Internal Process. priority. The data indicate that they did become well-structured, contented groups with facilitative leaders, whose only complaint was that they were not doing enough in the field. Both groups spent a fair amount of meeting time discussing information from the team leader meetings and in joint action planning. District profiles were put together in both teams, and directions from Walter were to "come prepared 21 to share everything you know about the districts of the day." During team meetings, observers noted that both team leaders encouraged open discussion and disagreement, although one or two members sometimes dominated meetings. Yurgen and Zoro, A Strategy of Probing The Y and Z teams were the most involved and proactive both in the regions and with the commissioner's office. Members on these teams interacted in a more dyadic fashion and less as a full group than the other teams. Interaction with the Regions. and Z teams showed a The questionnaire data indicate that the Y relatively high ability to predict regional needs and had more contact with the regions than the other teams (see Table 2). particularly the case for team Z. This is Meeting observations indicate that team members were the most active in projects and closest to the pulse of current issues in the field and in the organization. At the April progress report to the VC Yurgen spoke of great advances on school evaluation project. a The commissioner saw this as a great example of During the final May interview it was reported that initiation in the field. each team member had the task of informing Yurgen of important events in the district. The interviewee saw the team as proactive mainly because the whole team went to a district to describe a new program it had designed. At the April session Zoro talked about superintendent meetings, about events in the regions, and about activities that his in the region, including a mertJaers were involved with communication network he was designing. In the May interview, a team member reported that Zoro was frequently on the telephone with the "noisiest people in the district, so at least some of them think we are marvelous." Another plan was to assign one team member to each district as an intermediary. Interaction with the Commissioner's Office. 22 Both Yurgen and Zoro were very involved with the commissioner's office. The questionnaire data indicate that teams Y and Z had the highest scores on determining management expectations, formulating goals congruent with organizational goals, and communicating with the commissioner's office (see Table 3). When the commissioner formulated and assigned the task of reporting promising practices, Yurgen told his team he would take their comments and suggestions directly to the commissioner, rather than complaining or resisting like some of the other team leaders. He earned a good reputation with the other team leaders and the commissioner's office when he chaired the third team leader meeting and leaders rated it as their most effective. Yurgen "kept to the agenda while having people participate," one leader noted. Zoro also initiated activity. When the commissioner did not schedule an organization-wide day for team meetings, Zoro pushed the team leaders to take charge themselves, an idea he planned to discuss with the commissioner. Following the April progress meeting the commissioner commended both Yurgen and Zoro for being proactive in their regions. Internal Processes. Team meeting notes indicate that both the Y and Z teams spent the bulk of their time sharing information about current events in school districts and about promising practices. Both team leaders appear to have been much more directive than the other team leaders. Early in February, several members noted that internal communications were a problem in the Y team; members had been missing meetings and often did not know what other members were doing. Observation of a meeting late in February appeared to show some improvement when members discussed common needs in the region. Still, Yurgen often communicated one-on-one with team members between meetings rather than to everyone in the meetings. a "chairman" His style was called that of who enabled the team to take initiative: "He gets requests from 23 the field or generates ideas and asks a particular individual to do a piece of the work." Zoro also was a directive leader. Meetings appeared to be problem solving sessions; team members discussed the aspects of the organization that were hampering their work and what to do about it, or how to help with a a The May interviewee Between meetings Zoro also was active. already been made. person to do it. district deal Observation showed that Zoro tended to present plans that had problem. noted "he makes a determination of what is needed and tries to get the right He ' s a strong leader who knows the steps and therefore should be followed. Outcomes Although admittedly it was difficult to evaluate success in the first few months of the project, we asked members to evaluate their teams in the February questionnaire and in the May interviews. Internal Evaluation. The questionnaire results indicate that the V team was the most dissatisfied and the least cohesive (see Table 4). interview a During the May member complained that the team had not been able to get anything done because of internal conflicts. The questionnaire results show that in February the W and X teams had the highest ratings on individual satisfaction and group cohesiveness. particularly high for the X team. Scores were Indications that this pattern held, but that external activity was problematic, were raised in the May interview. This reaction is from an interviewee in Walter's group but could be interchanged with many of the comments from Xena's team member: "We're team. a good regional We have a good leader, we have good people, we do our homework, we have information about our region. and Walter is a good leader. . .meetings are a strength, we're a cohesive team, He's democratic, tolerant of opposition, brings 24 us exactly what he gets, and handles people well. The only problem is a lack of a specific mission in the field, no sense of priorities." The Y and Z -teams, the probing strategy, have satisfaction and cohesiveness scores that fall between the informing and the probing teams. May that a Y member reported "we're beginning to be more like It was not until a team." The Z team member rated his team as doing just what it was supposed to do. External Evaluation . In February 1984 I returned to the department for some external performance ratings (see Table 5). I asked the commissioner and the head of human resources to rank order the teams based on their performance and to explain the ranking. The commissioner told me that the team concept was finally taking hold, although it had taken a long time. In separate interviews, both the commissioner and head of human resources gave me the same rank ordering of teams, except that they reversed their top two ratings. Neither respondent thought that the intervals between teams were even. Both rated the V team way below all the others. as "the classic case of what not to do." Its performance was seen The V team was characterized as reactive rather than proactive and as the only failing team. next to the bottom. It had suffered high turnover. The W team was The commissioner commented furthermore that the team had deferred to one of its members who had strong field experience. This turned out to be a mistake, for the information received this way was not always accurate. Walter grew very frustrated with the limitations of his role, abdicated leadership, and eventually resigned as leader. The X team had the next highest rating. Its members were seen as happy and committed, and they satisfied many of the local superintendents. But the commissioner reported that they had not done "a damn thing," they were just happy to be with each other. The team met with superintendents who didn't understand why they were meeting. 25 The two highest ranking teams were the Y and Z teams, both of which were rated quite superior to the other teams. "super job." abilities. The Y team was thought to have done a Yurgen was good at "developing the team and he stretches their He has in-depth knowledge of the schools, and his school evaluations were a prototype for the rest of the organization." also seen as having done great work. This team did some school evaluations and "told the truth, which made some people angry. with a The Z team was But they did a thorough job The team also assigned people to districts, so there good end result. is one person to contact. This has really made a difference." These findings were not fully corroborated by the survey the department gave to randomly selected superintendents (see Table 5). Superintendents were asked to compare the service they were now getting to that of the year before, and to evaluate the extent to which they could get the help they needed. The data suggest that while team V lagged behind the other groups, teams X and Z helped the districts the most. The commissioner did not credit the survey much, however, because of low response rates. The results were not included in formal team evaluations and a new survey of the superintendents was planned for the future. DISCUSSION This research set out to build on Gersick's research (1988) examining the interaction process between teams and their environments. The goals here included identifying the actual content of strategies toward the environment, examining the role of the environment in influencing teams, and proposing relationships among external activity, internal process, and team performance. Categorizing Team-Context Interaction The first goal of this research was to document team strategies toward the external environment. We were able to differentiate three initial strategies 26 and to monitor the implementation of those strategies (see Table summary of strategies, activities, and performance ratings). team had little -outside contact. 6 for a The informing V It made decisions about how to serve the environment using existing member knowledge, and discouraged initiatives from This was intentional, as was the team's concentration on internal the field. team building. But, contrary to plan. Team V ended up fully occupied with internal conflicts and never quite got to informing outsiders--either the field or top management--of its plans for action. The team followed more of an isolation strategy,- not responding to external offers of help and buffering itself from outsiders. The parading W and V teams were each seen and responsive to some part of the external environment. They exhibited teams can vary their external activities. mixed approach, indicating that a For example, the W team had minimal contact with its region and relied on existing member knowledge (isolation), while maintaining high levels of visibility within the organization (parading) . The team moved beyond simple visibility to confrontation and conflict with top management. The mixed approach also is seen in the X team, which was visible in the field (reflecting a high level of outside contact to observe meetings and practices), and isolated from top management. Both the Y and Z teams planned to follow all outsiders. a probing strategy and did so with These teams did not use existing menrtber knowledge, alone, to map the external environment; members were encouraged to bring in new data with a view of the demands of the new task. These teams had the highest level of external contact, were proactive not only in testing potential interventions but also in actually implementing new programs, and presented an image to the field and to top management that they were doing overall interactive approach. 27 a good job. They epitomize an The data show us three types of interaction with outsiders-'isolation (formerly called informing), parading, and probing--differing on key These three strategies can be interpreted as different assumptions dimensions. toward learning. contemplation : Isolation means learning about the outside world through if you leave us alone to think and discuss, we will tell you what you need when we have figured it out. observation Parading means learning through The message here is that we want to watch you, . and to respond to your needs. to let you know that we are around, probing means following a to understand you, Finally, learning style captured in the epigram of one of Piaget's followers, "Penser, c'est operer," or to think is to operate. learning is through experimentation , Here trying out an idea and seeing the reaction, making an intervention and evaluating the result. This style appears to improve members understanding of means-ends relationships and allow it to accommodate to a more extensive, changing world. The Role of the Environment Thus far I have described a group as toward the external environment. a free actor following its strategy However, this is much too simple. In reality the environment reacts to the team and then both team and context mutually influence each other. Interaction between the group and its environment has patterns similar to that between the members and the group itself. The themes of power and influence appear to play an important role in group-environment relations. top management comes to a The teams begin to act and through their actions clearer idea of what it wants the teams to do, e.g., leaders should not meet by themselves but with the VC, teams should not have varying interventions but should concurrently implement promising practices. As top management begins to set constraints for the teams and to direct their activities power struggles ensue. Teams that overtly fight the direction end 28 up frustrated (Walter), while those that try to shape top management directives to be in line with their own plans, and vice versa (Yurgen) , find themselves held up as models of appropriate task behavior. Throughout this process of negotiating who is in charge, what will the task be, and how will performance be judged, there is over control. a great deal of ambivalence Some teams resist interference but want to be told what to do. The commissioner wants to give the teams autonomy, but constrains team behavior. With the commissioner's ambivalence in this case, it may have been inevitable that one team was the scapegoat and others were able to shine. Thus, the environment influences the team by setting limits on activity and by using examples from particular teams to help define the task and performance. Teams influence the environment by shaping that definition of task and performance. The external environment plays yet another role: that of echo chamber. News of the teams, what they are doing, how well they are doing it, gets fed into the rest of the organization and amplified. Early patterns appear to remain intact, with teams unable to change the reports about them. While the V team's troubles are told to the team leaders and the VC, the commissioner and the rest of the organization also hear them. If it had been in bad shape before, the V team is surely in trouble now because it has a reputation. On the positive side, when the Y team is praised as a model for school evaluation, and the Z team is congratulated for telling the truth to the superintendents, this news reinforces the positive image, making it easier for the teams to continue on the right track. The environment changes the whispers it hears into roars, underlining the importance of profile management in teams. Teams have to manage the information and images they send out because these are the images they will see 29 These images appear to get cast in concrete, and new reflected around them. data is interpreted to support the images, e.g., the superintendent ratings are discounted. It is important to note that different parts of the environment do not necessarily share the same perceptions and evaluations of the team, e.g., the commissioner and the superintendents. In this case, it is top management, not the customer, who has the largest impact on team evaluation, future team design, and rewards. Process and Performance Perhaps the most intriguing finding of this research is that external behavior seems to have If we had large impact on team performance ratings. a predicted performance using the traditional internal model, teams V, W, and X would have seemed prime candidates for top ratings. Their leaders plan to be participative and have members actively engaged in debate and decision making. Goal clarity and member satisfaction are seen as important goals. Yet the V team fails, and while members of the W and X team rate their satisfaction high early on performance, as rated by top management, is highest in teams Y and Z. The key proposition from this study is that teams dependent on outsiders and facing new tasks will be rated by outsiders as the highest performers if they emphasize external probing activities. Such teams can understand the demands of outsiders and initiate interventions in the field. They do not presume to understand their constituents, but venture out to revise old assumptions in light of a new charter. adequate for former tasks, in a While such assumptions may have been new endeavor the rules have changed. Finally, those who probe can promote the team and its activities to those who evaluate performance. The opening of the group's boundaries for probing activities may have some The cost of probing in this study was negative effects on internal processes. 30 low cohesion and satisfaction in the short run. external activity takes up a A high level of interactive lot of time and brings divergent views into the group, which may. inhibit team building. Groups with an external emphasis may run the risk of becoming underbounded (Alderfer, 1976); having external knowledge but not enough cohesion to motivate members to pull different perspectives together. Teams in this study overcame this problem through directive leadership that held them together until common experiences in the field provided solidarity. The teams that are visible in part of the external environment, but that are not as proactive with outsiders, are seen as mid-range performers. teams achieve more of a balance of internal and external activities. teams, These For these the more limited time and identification with outsiders, and even antagonism toward outsiders (W team), coexists with internal cohesion and satisfaction. Yet, these teams appear to run the risk of becoming overbounded, of letting their internal views and loyalties promote a "we versus them" mentality (Sherif, 1966) and negative external stereotypes (Janis, 1982). Cohesion for these teams may be limited to the short term if they cannot meet external demands. Still, these teams meet some external demands by watching outsiders and reacting to their needs. Furthermore, these teams raise the possibility that teams can satisfy both sets of demands. Finally, the data suggest that teams that are isolated from their environment have a high probability of failing. as lacking leadership skills, Although Victor is described it is possible that no leader can help a group that maintains isolation from those upon whom it is dependent. It is difficult to have a primary goal of defining the team, with no data on external expectations. In short, Internal conflict arises from ignorance about the outside world. I argue that a probing strategy toward the environment will 31 produce the highest performance in teams that must serve the needs of outsiders and that are evaluated by those outsiders. For groups facing a new, externally dependent task, it appears most effective in the long run to emphasize external activities first, even at the expense of short-term cohesion. Early on these teams can develop a rudimentary structure and some basic cohesion to organize themselves to diagnose and test plans for serving outside needs. Later, their cohesion will depend on affirmative interaction with the environment rather than on an ability to get along with one another. Future research will have to test whether complex internal and external processes can develop concurrently. Implications This study has both managerial and theoretical implications. For managers, the clear-cut conclusion is that initial team building needs to be tailored to the group's task. The balance between internal and external focus depends on how much the team needs outside resources, support, or information. Despite teams that automatically take an exclusively the advice of current texts, Teams internal focus may find themselves lower performers in the long run. with external evaluators, task allocators, and clients may find that developing externally focused roles is as important as developing internal process skills (Ancona & Caldwell, 1988). This is not a strategy that all groups implicitly follow, so organizations may want to expose team leaders to the external perspective. Furthermore, teams need to learn to monitor and manage their external profiles if only because the external organization magnifies the image that the team presents to it. From a theoretical point of view, this study elaborates on the process of team-context interaction. It calls for studying individuals in groups, but adds another level of analysis, groups in organizations. including a It calls for new set of variables in group research, specifically, 32 a group's approach to its external environment, a group's mix of internal and external processes, and modes of environmental influence on group behavior. Finally, it calls for investigating the mutual influence of environmental constraint and team action. Although it is difficult to distinguish which of forceful leadership, or updating information about the field, or initiating activity, or promoting the team to top management, caused probing teams to be rated as high performers, clearly some of these activities make a difference. Future research is needed to confirm and expand the findings of this study, including statistical clustering of activities into external strategies and testing the relationships among processes and performance. Research can now focus on larger samples and more diverse tasks, with an emphasis on hypothesis testing. Results here suggest that this move will be worthwhile. The findings in this study come from a small sample; five groups within one organization, doing one task. many organizational groups. Yet the teams in this study share traits with New product teams, organizational task forces, and strategic decision making groups are just a few examples of teams that face unstructured tasks and high external demands. All such teams may require theoretical lens highlighting team-context interaction for adequate understanding. 33 a new NOTES Both refer to The term teams is used here interchangeably with groups. others as a who themselves as a group, are seen by see set of individuals designated by the achieve a task work interdependently to group, and must & Morris, Ancona, 1987). (Hackman 1975; organization 1. a Although much of the work on group process tends to view the group as a closed system, separated from the organizational context, this is clearly a For example, work in the generalization for which there are exceptions. accounts for team interaction with (Colman & Bexton, 1975) tradition Tavistock community the team borders. larger beyond figures and the authority external discuss goal formulation in relation to often process models addition, group In external demands (Schein, 1988). However, by and large these are exceptions to the rule and the group process literature must speak to the absence of work on team-context interaction. 2. The external perspective builds on a shift in level of analysis that has taken place in organization theory where resource dependence, population ecology, and interorganizational theorists have studied organizations functioning within environments, rather than merely as settings for managerial functioning (see Aldrich & Pfeffer, 1976; McKelvey, 1982; Whetten, 1983). Studies have shown that organizations not only adapt to environmental demands, but that they also mold, enact, and manage their dependence on others or fall prey to the forces of environmental selection (Astley & Van de Ven, 1983). 3. REFERENCES Abelson, R.P. 1976. Script processing in attitude formation and decision making. In J.S. Carroll & J.W. Payne (Eds.), Cognition and social behavior Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates. . Alderfer, C.P. 1976. Boundary relations and organizational diagnosis. In M. Meltzer and F. Wickert (Eds.), Humanizing organizational behavior Springfield, IL: Charles Thomas. . Aldrich, H.E. & Pfeffer, J. 1976. Environments of organizations. In A. Inkeles, J. Coleman & N. Smelser (Eds.), Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 2: 79-105. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Review. T.J. 1984. Managing the flow of technology: technology transfer and the dissemination of technological information within the Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press. organization Allen, R&D . Ancona, D.G. 1987. Groups in organizations: Extending laboratory models. In C. Hendrick (Ed.), Annual review of personality and social psychology: group and intergroup processes Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. . Ancona, D.G. & Caldwell, D.F. 1988. Beyond task and maintenance: Defining external functions in groups. Group and Organization Studies 13, 4: . 468-494. Ancona, D.G. & Caldwell, D.F. 1989. Information technology and work groups: the case of new product teams. In J. Galegher, R.E. Kraut & C. Egido (Eds.), Intellectual teamwork: social and technological bases of cooperative work Lawrence Ehrlbaum Associates, Inc. . Astley, W.G. & Van de Ven, A. H. 1983. Central perspectives and debates organization theory. Administrative Science Quarterly 28: 245-273. in . Bailyn, L. 1977. Research as a cognitive process: 11: 97-117. analysis. Quality and Quantity Implications for data . Bales, R.F. 1983. SYMLOG: A H.H. Blumberg, A. Social P. Interaction. 2: practical approach to the study of groups. In Kent & M.F. Davies (Eds.), Small Groups Hare, V. 499-523. Bettenhausen, K. & Murnighan, J.K. 1985. The emergence of norms in competitive decision-making groups. Administrative Science Quarterly . 30: 350-372. & Fujimoto, T. 1987. Overlapping problem solving in product development. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Working Paper 87-048. Clark, K.B. Coleman, Arthur D. 1975. Group relations reader In Arthur D, Coleman & W. Harold Bexton (Eds.). Saulsalito, CA: GREX, cl975. . Drucker, Peter F. 1978. The coming of the new organization. Business Review January-February 1988, 1: 45-53. . 1 Harvard am Dyer, W.G. 1977. Team building: Addison-Wesley. Issues and alternatives . Reading, MA: 1982. Designing the innovating organization. Organization dynamics; Winter, 5-25. Galbraith, J.R. Gersick, C.J.C. 1988. Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model 31: 9-41. of group development. Academv of Management Journal , The constitution of society: outline of the Giddens, Anthony. 1984. theorv of structu ration Berkeley: University of California Press. . Gladstein, D. 1984. Groups in context: A model of task group effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly 29: 499-517. , Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. 1967. The discoverv of grounded theorv: London: Wiedenfeld and Nicholson. for gualitative research strategies . P. (Ed.). 1986. The impact of task and technology on group performance. In P. Goodman (Ed.), Designing effective work groups 216. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Goodman, 198- : Hackman, J.R. 1982. A set of methods for research on work teams. Technical Report #1, Research Program on Group Effectiveness, Yale School of Organization and Management. December. Group tasks, group Richard & Morris, Charles G. 1975. interaction process and group performance effectiveness: A review and proposed integration. In Leonard Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psvchologv 8:45-99. New York: Academic Press. Hackman, J. , Hackman, J.R. & Walton, R.E. 1986. Leading groups in organizations. Goodman (Ed.), Designing effective work groups 72-119. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. In P. : Hanlon, M. 1980. Observational Methods in Organizational Assessments. In Organizational assessment: perspectives on the m anagement of Edited by organizational behavior and guality of work life 349-371 John Wiley & York: E.E. Lawler III, D.A. Nadler and C. Cammann. New Sons, Inc. : Janis, I.L. Groupthink 1982. . . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Kanter, R.M. 1983. The change masters: innovation for productivitv american corporation New York: Simon and Schuster. in the . Katz, into the managerial roles and in a major supervisors project career paths of gatekeepers and 103-110. facility. Management 11: R. & Tushman, M. R&D 1981. An investigation R&D . Kazanjian R.K. & Drazin, R. 1986. Implementing manufacturing innovations: Critical choices of structure and staffing roles. Human R esource Management 25, 3: 385-403. . D.H. 1985. The one-firm firm: What makes Management Review. 27: 3-13. Maister, it successful. Sloan McKelvey, B. 1982. Organizational systematics: tazonomy. evolution, and Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. classification . 1972. Merger as a response to organizational interdependence. Administrative Science Quarteriv 17: 382-394. Pfeffer, J. . Pfeffer, J. 1986. A resource dependence perspective on intercorporate relations. In M.S. Mizruchi and M. Schwartz (Eds.), Structural analvsis 117-132. New York: Academic Press. of business : Pfeffer, J. a & Salancik, G.R. 1978. The external control of organizations New York: Harper & Row. resource dependence perspective : . E.H. 1988. Process consultation: its role in organization development. Vol. 1. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Schein, Sherif, M. 1966. In common predicament: social psychology of intergroup conflict and cooperation Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. . Taylor, S.E., Crocker, J. & D'Agnostino, J. 1978. Schematic bases of social problem solving. Personality and Social Psvchologv Bulletin 4: 447-451. . Tushman, M. 1977. Special boundary Administrative Science Quarterly roles in the innovation process. . 2: 587-605. 1979. Work characteristics and subunit communication structure: A contingency analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly 24: 82-98. Tushman, M. . Tushman, Michael & processess Van de Ven, A. New York: Tsui, & Nadler, . Glenview H. & Ferry, Wiley. David. 1988. Qrganization design: concepts, tools Illinois: Scott, Forseman and Company. D.L. 1980. Measuring and assessing organizations. Anne S. 1987. Defining the activities and effectiveness of the human resource department: a multiple constituency approach. Human Resource Management . 26: 35-69. 1988. Task partitioning: an innovation process variable. Cambridge: Sloan School of Management Working Paper 2030-88. Von Hippel, E.A. Vroom, V.H. & Jago, A.G. 1974. Decision making as a social process: normative and descriptive models of leader behavior. Decision Sciences . 5. Whetten, D. 1983. Interorganizational relations. In J. Lorsch (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. . Yin, R.K. 1984. Case studv research: design and methods Sage Publications. . Beverly Hills, CA: (0 3 r- ^C > 2 o c = (^1 o o CO Q. QC 111 Q < UJ _i a z o < CO ill o z LU CC HI U. Q UJ -J OQ < I « > w c CSi Tt ° O) J2 u CA "5 0) (D k. o> w W cc >. c:) o .- E 1- C\J to k. CO o z M O O O LU q: LU X I -^ c 2 II in -^ 0) 0) CO eg CO I" Z 1- > CM If) t^ 00 °-0 2 o E 3 ^ _>. 5 C o k. CO Q. ^' ^° .2 -D To C3) E o g . ^ W D CO ^ ? <-> * C3) »- CO CO "D i: « ^-» (/> II ^ o < DC LJJ E Q> t3 2 Ec o o 0) (0 o cj o in Tt CVJ 1-^ T-^ r>; o C c _o w 0) LU _J CD < O .52 0)1 N col lii O -Q Q E =0)o 0)E o t3 CO _ CO To ctE E O 13 p _l C i: o i: (/) .-K © C (O 8 E o % E (/) (A 0) ^8 C > 0) UJ o z I o cc UJ Q. ts .> o <]> t3 «= 0) O o a) a: m CO O) X c E cc c < UJ 0) c 0) Q UJ I- < GC >I c (0 o c Q> Q. CO X UJ ui UJ _l CD «= 0) 0) p (0 o UJ I- if ^ c g i: CO CO UJ CO O UJ CO CO LU z LU > & UJ o c E k. o o Q. MIT LIBRARIES DUPL 3 TOflO 2 DD5bbfl7T D