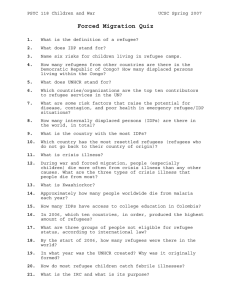

THE ROSEMARIE ROGERS WORKING PAPER SERIES

advertisement