Moving from Research to Practical Application in Dropout Prevention

advertisement

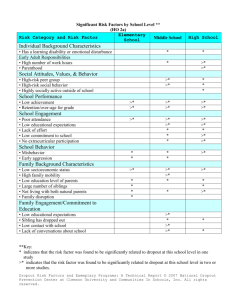

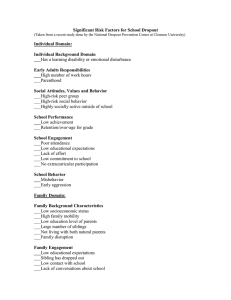

Moving from Research to Practical Application in Dropout Prevention Presented by: Pat Homberg, Executive Director Susan Beck, Assistant Director Debbie Harless, Coordinator Office of Special Education Prepared by: Loujeania Williams Bost, PhD Director, National Dropout Prevention Center for Students with Disabilities Module 2 Intensive Technical Assistance Objectives 1. Increase participants’ awareness and understanding of dropout and its effect on students with disabilities. 2. Provide participants with an overview of recent research on the causes and risk factors associated with dropout. 3. Identify effective practices that increase student engagement and school completion. What the Research Tells Us: I. What is Dropout? 4 Dropout: A Process of Disengagement • Not an isolated event • Elementary years, process begins • Elevated dropout rates reported among children who were rated as highly aggressive by their 1st grade teachers (Ensminger & Slusarcick, 1992). • Dropouts could be distinguished from graduates with 66% accuracy by the third grade using attendance data; and • Identification of dropouts can be accomplished with reasonable accuracy based on review of school performance (behavior, attendance, academics) during the elementary years (Barrington & Hendricks, 1989) . • Students who had repeated a grade as early as K – 4th grade were five times more likely to drop out of school (Kaufman & Bradby, 1992). Predictors of Dropout (Balfanz & Herzog, 2005; 2006) 1. The four strongest predictors – determined by the end of sixth grade 1. Poor attendance (14%) 2. Poor behavior (17%) 3. Failing math (21%) 4. Failing English (16%) 2. Sixth graders who do not attend school regularly, receive poor behavior marks, or fail math or English • 10% chance of graduating on time • 20% chance of graduating a year late Predictors of Dropout (Continued) 3. Students who repeated middle school grades are 11 times more likely to drop out than students who had not repeated. 4. A student who is retained two grades increases their risk of dropping out of high school by 90% (Roderick, 1995). 5. Transition between schools Middle school/junior high school to high school Predictors of Dropout (Continued) (Balfanz & Herzog, 2006) 6. Students who enter ninth grade two or more grade levels behind their peers have only a one in two chance of being promoted to the tenth grade on time. 7. Ninth grade retention is the biggest predictor of dropouts. 8. The biggest fall off for students is between ninth and tenth grade What the Research Tells Us: II. Causes and Risk Factors Risk Factors • Education, Sociology, and Economics • Demographic characteristics and family background • Past school performance • Personal/psychological characteristics • Adult responsibilities • School or neighborhood characteristics Risk Factors (Continued) • Personal/psychological characteristics – Commitment to schooling and ability to follow through on this commitment, low self-esteem & locus of control, low educational expectations or plans • Adult responsibilities – Employment, caring for a child • Working >20 hours/week positively associated with dropping out • Pregnancy positively associated with dropping out • School or neighborhood characteristics – Poor neighborhoods vs. wealthier neighborhoods – Higher in urban schools; rural; suburban Risk Factors (Continued) • Demographic Characteristics – African American, American Indian/Native American, Hispanic/Latino American • Approximately half of African American students do not receive diplomas with their cohort. • Less than 50% of Native American Students graduate each year (Faircloth & Tippeconnic, 2010). • Native students have the highest dropout rate in the nation (Indian Nation At Risk, 1991). • Hispanic students are the largest minority group in our Nation’s schools. • Fewer than half of all Hispanic children participate in early childhood education programs, and far too few Hispanics students graduate from high school. Risk Factors (Continued) • Family Background • Family income, SES, family involvement, families who receive welfare, parents’ educational attainment, single parent home, limited English proficiency, parent or sibling dropped out • Students from low SES families are four times more likely to drop out than their high SES peers • Past School Performance • Low grades, poor test scores, retention & age, disciplinary problems, truancy, spending little time on homework Taking a Closer Look III. Status and Alterable Variables 14 Status Variables Variables associated with dropout that are difficult and unlikely to change • • • • • • Age Gender SES Ethnicity Native language Region • • • • • • Mobility Ability Disability Parental employment School size and type Family structure Alterable Variables Variables associated with dropout that can be changed • • • • • • Grades Disruptive behavior Absenteeism School policies School climate Parent engagement • Sense of belonging • Attitudes toward school • Educational support in the home • Retention • Stressful life events Examples of Status and Alterable Variables Class of Variables Status Variables Alterable Variables Student Disability (e.g. LD, EBD) Attendance (e.g. sporadic) Family Structure (e.g. single parent family) Supervision of free time (e.g. rarely occurs) Peers Intelligence (e.g. low IQ) Identification with school (e.g. alienated) School Socioeconomic Status (e.g. living in poverty) Monitoring of Student Progress (e.g. consistently occurs) Community Geographic Features (e.g. urban) Support Services (e.g. available) Source: Christenson, Sinclair, & Hurley (2000) Taking a Closer Look IV. Pull and Push Factors 18 Pull Factors That Lead to Dropout • Pull Factors • Reported by students • Compete with the goal of regular school attendance • Compete with successful school completion as a first priority or • Have to be performed in conjunction with attending school Push Factors That Lead to Dropout • Push Factors • Reported by students • Located within schools • Cause students to feel unwelcome • Students resist or altogether reject schooling • Manifest disruptive behavior, chronic absenteeism, and completion cessation of academic effort Pull Factors That Lead to Dropout (Continued) Pull Factors • • • • • • • • Had to get a job Had to support family Became pregnant Wanted to have a family Wanted to travel Friends dropped out Got married, or planned to get married Had to care for family member due to illness Push Factors That Lead to Dropout (Continued) Push Factors • • • • • • • Did not like school Could not get along with teachers/students Suspended too often Expelled too often Did not feel safe at school Did not belong Could not keep up with school work/failing school What the Research Tells Us: V. Theoretical Models of Prevention Theoretical Conceptualizations for Preventing Dropout and Promoting School Completion (Finn, 1993) • School Completion = Engagement in School and Learning • KEY ELEMENTS • Student Participation • Identification with School • Social Bonding • Personal Investment in Learning Theoretical Conceptualizations for Preventing Dropout and Promoting School Completion (Continued) (Fashola & Slavin,1998) • Incorporating personalization by creating meaningful personal bonds; • Connecting students to an attainable future; • Providing academic assistance to help students perform well in their coursework; and • Recognizing the importance of families in the success of their children’s achievement and school completion. Theoretical Conceptualizations for Preventing Dropout and Promoting School Completion (Continued) (Dynarski, 2000) • Creating small schools with small class sizes • Building relationships and enhancing communication between students and teachers • Providing individual academic and behavior support • Helping students address personal and family issues through counseling and access to social services • Orientation towards assisting students in efforts to obtain GED certificates. Theoretical Conceptualizations for Preventing Dropout and Promoting School Completion (Continued) (Christenson, 2002) • Help students develop connections with the learning environments across a variety of domains • Engagement is viewed as a multi-dimensional construct involving four types of engagement and associated indicators Four Types of Engagement & Associated Factors (Christenson, 2002) • Academic engagement refers to time on task, academically engaged time, or credit accrual. • Behavioral engagement includes attendance, avoidance of suspension, classroom participation, and involvement in extracurricular activities. • Cognitive engagement involves internal indicators including processing academic information or becoming a self-regulated learner. • Psychological engagement includes identification with school or a sense of belonging. Theoretical Conceptualizations for Preventing Dropout and Promoting School Completion (Continued) (Lehr et al., 2003) • Personal/affective (e.g., retreats designed to enhance self-esteem, regularly scheduled classroom-based discussion, individual counseling, participation in an interpersonal relations class) • Academic (e.g., provision of special academic course, individualized methods of instruction, tutoring) • Family outreach (e.g., strategies that include increased feedback to parents or home visits) Theoretical Conceptualizations for Preventing Dropout and Promoting School Completion (Continued) Lehr et al., 2003) • School structure (e.g., implementation of school within a school, re-definition of the role of the homeroom teacher, reducing school size, creation of an alternative school) • Work related (vocational training, participation in volunteer or service programs) Theoretical Conceptualizations for Preventing Dropout and Promoting School Completion (Continued) (Principles for Keeping Kids in School: Kortering, 2004) Increase the Holding Power of Schools for SWD • Students must have a reason to want to complete school. They must understand the relevance of graduation to their future. • Students need and want to access an adult who will encourage them to stay in school and help them to succeed.. What the Research Tells Us: VI. Effective Interventions and Models 32 Effective Approaches for Intervention • Implementation of early intervening strategies that are universal in nature and focused on prevention. • Program offerings to provide extra help for certain groups of students who share particular risk factors • Extensive or personalized help for targeted students. • Interventions occur over time, usually months or years • Interventions that are strength based and involve a variety of contexts Non Effective Approaches for Intervention • Short-lived approaches • Punishment-oriented approaches • Approaches not focused on engaging students in school • Practices not based on data • Practices utilizing practices without evidence of effectiveness General Practices Related to Dropout Prevention • • • • • • • • Comprehensive diagnostic data systems Early warning systems Provide rigorous and relevant instruction Provide academic support Provide personalized instruction and learning Instruction on behavior and social skills Supportive school climate Family engagement Interventions Influenced by Educators • Focus on factors linked to dropout • Positive school climate • Attendance • Behavior • Academic performance • Family engagement • Student engagement • Evaluate policies and procedures regarding dropouts • Implementation of evidence-based strategies/interventions • Interventions must be matched to student needs Effective Models (Continued) Original Study Outcomes (Cobb, 2005) • Staying in school; retention in support programs designed to keep students in school • Attendance • Engagement with school • Physical or verbal aggression • Self-concept; self-esteem Conclusions (Cobb, 2005) FINDINGS •Cognitive-behavioral Interventions – (YES) • Appears best for high incidence disabilities •Applied Behavior Analytic Interventions – (Cautious Yes) • Appears useful to reduce verbally and physically aggressive behavior and both high and low incidence disabilities •Counseling Interventions – (No Judgment Can Be Made) • Appears useful specifically for students with emotional disorders Recommendations • Diagnostic processes for identifying studentlevel and school wide dropout issues • Targeted interventions for a subset of middle and high school students who are identified as at risk for dropping out • School wide reforms designated to enhance engagement Use a Diagnostic Approach Institute of Educational Science Dropout Prevention Practice Guide Comprehensive, longitudinal, student level databases that include unique student identifiers Enables SEAs and LEAs to conduct causal analysis Use data to identify incoming students with histories of academic problems Monitor Academic Progress of all students Review student level data to identify students at risk of dropping out Monitors student’s sense of belonging Targeted Interventions • Caring Adult Advocates • Academic Support & Enrichment • Improvement in Behavior and Social Skills School wide Reforms • Personalized Learning Environments/Processes • Rigorous and relevant instruction in academic and career skills What We Know About Patterns of Risk (Allensworth, 2007) Freshmen with 0–4 absences in a 90-day grading period have a greater than 80% rate of graduation, while freshman with 10–14 absences in the same period graduate at a 40% rate. Freshmen with no course failures have a greater than 80% chance of graduating, while those with two failures have a 55% graduation rate, and those with four failures have a 30% rate. Freshmen with a GPA of 3.5 or higher have a nearly 100% graduation rate, while those with a 2.0 GPA have a 70% rate and those with a 1.0 have a 30% rate. Sixth-grade students who fail math or English, have an 80% or lower attendance rate, or earn an unsatisfactory behavior grade have just a 10–20% likelihood of graduating high school in five years. Key Risk Indicators Student absences Grade retention Low academic achievement Behavior Family Engagement School Climate Critical transition points Areas Identified • • • • • • • • Adult Advocates Family Engagement Academic Success 9th Grade Transitions Student Engagement Vocational/ Career Preparation Interpersonal Skills Class and School Restructuring Adult Advocates Role of Mentor Practical Social/Emotional • • • • Provide students with support and encouragement • Convey the message to students that teachers care about their future • Help students see the value in school and graduating from school • Model positive behavior and decision-making skills • • • Monitor students’ attendance Check homework completion Help students develop conflictresolution skills Communicate with families and teachers Arrange for tutoring and social services Help students establish postsecondary and career goals Strategies that Increase Family Engagement • Conduct home visits to develop relationships with family members • Provide transportation or arrange car-pooling to school events and offer to meet parents in locations that are convenient for them • Provide assistance for parents in reinforcing classroom instruction and providing behavioral support for their children at home • Contact parents with positive information about their children and thank them for their support Strategies to Increase Academic Success • Tutoring / individual instruction • Study skills and test-taking classes • Individual or small group instruction in reading and core academic areas • Extra instruction / credit recovery through Saturday school, after-school, or summer programs • Self-paced online programs Ninth-Grade Transitions • Use current high school students as mentors for incoming freshman • Hold a freshman class orientation while students are in middle school • Institute summer programs at the high school to increase students’ academic skills, orient them to the layout of the school, and enable them to meet high school teachers Ninth-Grade Transitions • Address the instructional needs of students who enter high school unprepared for rigorous academic work • Personalize the learning environment through small class sizes, a freshman academy, mentoring programs, or student participation in school activities Strategies for Increasing Student Engagement • • • • Create small learning communities Show an interest in students on a personal level Focus on the development of peer relationships Encourage students to participate in school activities • Use instructional techniques that emphasize the relevance of classroom learning Career and Vocational Preparation • Classes focused on employability skills across a variety of occupations • Occupationally specific programming in a trade, such as carpentry or plumbing • Training in related skills such as computer literacy, job seeking, and workplace behavior • On-the-job training for which students can earn credits • Career days at which students can gain information from local employers • Connections to postsecondary institutions Interpersonal Skills Self Determination • • • • • • • Decision making Problem solving Goal setting Self-advocacy Leadership skills Self-management Self-regulation Interpersonal Skills Social Skills • • • • • Meeting people Conflict management Active listening Starting conversations Appropriate body language, gestures, and facial expressions Interpersonal Skills Life Skills • • • • • • • Conflict management Social skills Goal setting Leisure skills Self-advocacy Community participation Job-seeking skills Class / School Restructuring • • • • Reduce class sizes Create freshman academies Establish a school-within-a-school Provide opportunities for team teaching What we Learned • Dropout is COMPLEX – there is no one solution – the costs are substantial • Dropout does not occur overnight • SWD are at considerable risk • We must identify and address risk factors • Risk factors have predictability • Educators can influence risk factors • Family engagement is critical • Evidence-based practices are essential What we Learned • Existing district and school data systems can be used to help learn about students at risk for school failure and dropout. • Adults matter in youth’s lives • Instruction must be revelant, rigorous and engaging • Use of a continuum of tiered interventions can be used to address risk in academics and behavior New Lessons Learned • Measuring risk indicators is an important first step in intervention • A systems approach is required to make significant gains • Early warning intervention systems can support on-track success at each level of school • States can support LEAs by providing sufficient infrastructure support to support implementation of initiatives at the local level. Additional Information Contact: phomberg@k12.wv.us sbeck@k12.wv.us dlharless@k12.wv.us lbost8@uncc.edu