Document 11057664

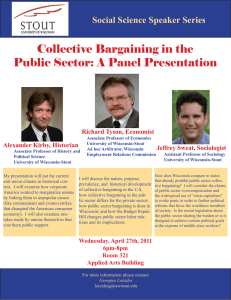

advertisement