a GAO MARITIME SECURITY FLEET

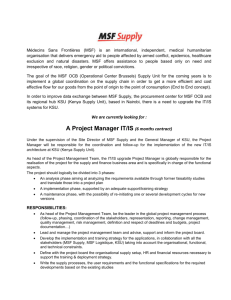

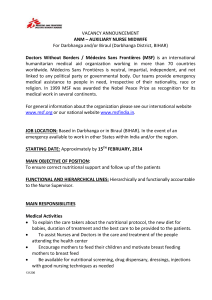

advertisement