GAO MILITARY TRAINING Strategic Planning and Distributive Learning

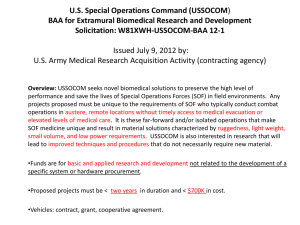

advertisement