GAO WARFIGHTER SUPPORT DOD Should Improve

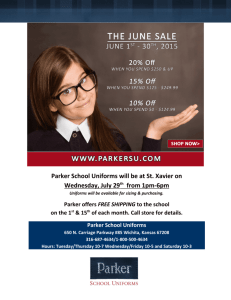

advertisement