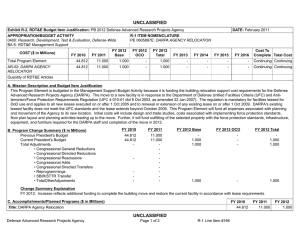

DEFENSE ADVANCED RESEARCH PROJECTS AGENCY

advertisement