GAO ARMED FORCES INSTITUTE OF PATHOLOGY

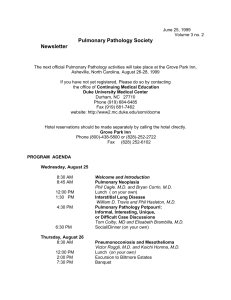

advertisement