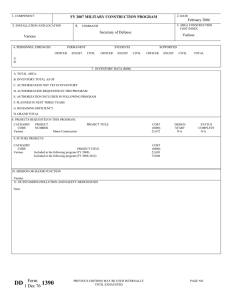

GAO DEFENSE INVENTORY Opportunities Exist to

advertisement