GAO MILITARY PERSONNEL DOD Actions Needed

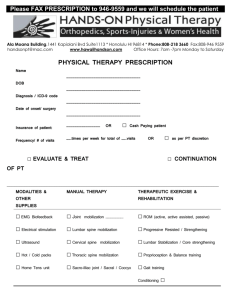

advertisement