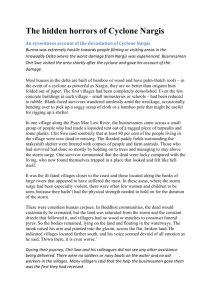

GAO BURMA UN and U.S. Agencies Assisted Cyclone

advertisement