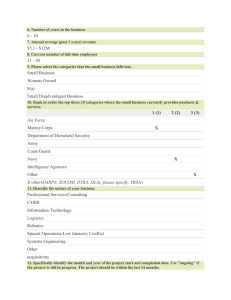

GAO WARFIGHTER SUPPORT Actions Needed to

advertisement